Hiroichiro Maedako, a proletarian writer who came to Chicago in 1907, once wrote in one of his articles the following confession:

“When I was walking on Armour Avenue, a woman called out to me, ‘Hello, honey boy, come on in—you want skebe?’From the beginning of the encounter, I was dumbfounded by this flatly fired off Japanese word: skebe.”1

Then in 1910, while in a carriage returning to his hotel, Kasho Kono passed four or five Japanese women riding in a fine-looking carriage on State Street. Kono asked the driver who they were, and the driver answered that they were Japanese skebe.2 So it seems that by the early 1900s, the Japanese word, skebe (pronounced “skay-bay”), was well known in Chicago. What does skebe mean? A skebe is not just a pervert, it's a term that is commonly and inclusively used to describe an emotional state between lust and eroticism.

According to an entry in the Encyclopedia of Chicago, “Chicago owes its reputation as a corrupt city in part to the history of one “vice” in particular —prostitution”3 and was well known as a center of white slaves, taking advantage of its location as a hub city for all the railroads in the country. In Chicago, “municipal officials actively encouraged the extralegal persistence of the city’s red-light districts” and those districts “usually overlapped that handful of neighborhoods where immigrants and blacks were able to locate housing and work,” similar to the situation in New York City.4

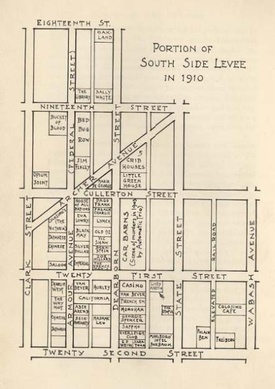

There were three levee (flood control) districts in Chicago at the turn of the century: the north, west and south sides, next to Little Sicily; Little Italy; the Jewish Ghetto; and Chinatown. The south side levee was a very popular “bustling red-light district located just south of The Loop, the city’s central business district” which came to simply be called “The Levee.”5 In the early years of the twentieth century though, the boundaries of the Levee moved nearly one-mile south, “bounded by Clark Street, Wabash Avenue, and Eighteenth and Twenty-second streets”6 with the creation of New Chinatown at the intersection of Archer Avenue and Twenty Second Street. Armour Avenue, where Maedako strolled, east of Clark Street and intersecting Archer Avenue, was one of the nation’s most infamous sex districts.7 Furthermore, “the Black Belt [predominantly African-American area] was largely coincident with, though not fully contained within, both the old and new Levee districts.”8

According to an article in McClure’s Magazine, “Gross revenue from prostitution in Chicago in 1906 was $20,000,000 and probably more. There were at least ten thousand professional prostitutes” run by “criminal hotels, houses of ill-fame, cheap dance-halls and saloons, and men — largely Russian Jews.” In total, there were “at least three hundred and fifty good-sized houses of prostitution in Chicago.”9

In 1910, Chicago mayor Fred Busse, who was pressed by local reformation groups such as The American Vigilance Association, created the Vice Commission of Chicago, a municipal body appointed by the Mayor and the City Council of the City of Chicago, and ordered them to investigate prostitution. The Vice Commission publicized a report of their findings in 1911, and gave more conservative numbers than McClure’s Magazine; in their estimation, the number of prostitutes in Chicago was approximately 5,00010, and they reported that annual industry profits in the city of Chicago alone were between 15 and 16 million dollars.11 Among those 5,000-10,000 were a few Japanese women, some of whom were mentioned by writers of the day. For example, Otojiro Kawakami and his troupe, who performed in Chicago in October 1899, found that there were about six Japanese women in an audience of two hundred. Four out of those six were well-known Japanese prostitutes, such as one who went by the name “Tami.”12

In 1904, Japanese government officials expressed their concern when more than thirty Japanese geisha came to St. Louis, Missouri to perform “Miyako Odori” at the Japanese garden on the “Pike” of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. The officials said, “We need to send them back to Japan quickly. Once they drift apart, they may be in danger from those who would take advantage of their linguistic disability and send them to brothels run by the wicked from Chicago. That would definitely cast shame on the Empire. The Japanese consul in Chicago warned us that once they are sent to dens of prostitution, the government cannot rescue them because the owners of these dens use bribery to control the officials in Chicago, so the Japanese cannot approach them.”13 Regardless of the warning, one of the geisha, Misa Okada, escaped from a carriage carrying the group to the train station and disappeared.14

Writers of the turn of the century occasionally mentioned Japanese brothels. In his most famous novel, The Jungle, published in 1906, Upton Sinclair wrote: “They get as much as forty dollars a head for girls, and they bring them from all over.” “French girls are bad, too, the worst of all, except for the Japanese. There’s a place next door that’s full of Japanese women.”15

Furthermore, Karen Abbott, author of the novel, Sin in the Second City, which depicted “The Levee’s most famous brothel, the exclusive Everleigh Club,”16 described Japanese prostitutes as “unable to bear the frigid Chicago climate, [practicing] their profession during the winter months clad in long woolen underwear.17 And finally, the Japanese socialist writer, Kiichi Kaneko, who moved to Chicago from New York in 1906, reported to Japan that Japanese prostitutes in Chicago accepted only white men and urged his comrades in Japan to do research on this situation.18

Did those white customers learn the Japanese word, “skebe” from Japanese prostitutes, or did Japanese customers teach the word to non-Japanese prostitutes in Chicago?

“Skebe” as a profession for single Japanese women in Chicago

The 1880 census was the first time that a Japanese woman was recorded as living in Illinois. She was one of three Japanese in Illinois and she lived in Chicago. Details are unknown, but the Chicago City Directory recorded a Japanese by the name of “Hockeyama Onna” (Hockeyama’s woman). This woman was a peddler and lived at 243 W. 16th Street.19 Was the woman recorded in the 1880 census this woman, or a totally different person? We can’t be sure.

The 1890 census recorded one woman among the thirteen Japanese living in Illinois. This woman was Yasu Hishikawa, a Japanese medical doctor who received her license from the State of Illinois after graduating from the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago in 1889.20 The 1900 census found eighty-eight Japanese living in Illinois, and sixteen among them were female. Of these, thirteen were adult women, and they all lived in Chicago. Two of them were married, and eleven were single. Of those single adult women, one was an actress named Hiro Okabe, and another was Hisa Nagano, a medical student at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Chicago.21 Of the remaining nine, one was a domestic servant, and eight women all lived at 2026 Armour Avenue.

There can be no doubt that these eight were prostitutes since Armour Avenue was a popular district for the sex trade. By 1910, 287 Japanese lived in Illinois. Forty-two were female, and twenty-six of them were adult women. All of the adult women lived in Chicago; sixteen were married and ten were single. Out of the ten single Issei women, one was a helper for the family business of Takeda Shoten at 2917 Prairie Avenue,22 three were house servants at 502 Sheridan Road and 94 E Walton Place, one was an entertainer at 1227 71st Street, and five were prostitutes who lived at 2026 Armour Avenue.

A review of Japanese women’s occupations in pre-war Chicago from 1890 to 1940 census information reveals that the rough pattern of possible occupations for Japanese Issei women (with the exception of a few elite single Christian women in 19th century Chicago,) regardless of whether they were married or single, did not change in fifty years. Their choices were extremely limited. Basically, they could only engage in domestic service and family businesses, working at Japanese goods stores, restaurants, and Japanese language schools, helping their husbands, most likely due to their limited English skills. The only single Issei women in Chicago who overcame this linguistic handicap were a small number of entertainers, prostitutes, and one female photographer in the 1920s. These were women who could depend on their physical strength or occupational skill to make a living, not on their communication skills in English. For this reason, the “skebe” trade should be considered an important occupation in Chicago Japanese women’s history.

Notes:

1. Maedako, Hiroichiro, “Mizukara Onore wo Okuru Sho,” Nichibei Jiho January 1, 1920.

2. Kono, Kasho, Kokkei Sekai Kenbutsu, 1911.

3. The Encyclopedia of Chicago, page 651.

4. Heap, Chad, Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885-1940, page 25-26.

5. Ibid, page 37.

6. Ibid, page 40.

7. The Encyclopedia of Chicago, page 651.

8. Heap, page 42.

9. Turner, George Kibbe, “The City of Chicago: A study of the Great Immoralities,” McCllure’s Magazine, April 1907.

10. The Social Evil in Chicago: a study of existing conditions with recommendations, page 33.

11. Ibid, page 71.

12. Ito, Kazuo, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-shi, page 126.

13. Nichibei Shuho, October 1, 1904.

14. Nichibei Shuho, Sept ember 17, 1904.

15. Sinclair, Upton, The Jungle, page 353.

16. The Encyclopedia of Chicago, Page 652.

17. Abbott, Karen, Sin in the Second City, page 13.

18. Osaka Heimin Shinbun, June 15, 1907.

19. Chicago City Directory, 1880.

20. Day, Takako. “Atypical Japanese Women - The First Japanese Female Medical Doctor and Nurses in Chicago - Part 1,” Discover Nikkei, December 6, 2018.

21. Ibid.

22. Day, Takako. “The Chicago Shoyu Story—Shinsaku Nagano and the Japanese Entrepreneurs - Part 1,” Discover Nikkei, February 17, 2020.

© 2021 Takako Day