I descend from a long line of samurai families. I am the fifth of six children of my parents, Taeko Yoshioka and Noel Braid.

My parents met during the Japanese Occupation when Dad was on R&R there during his tour of duty in the Korean War. At 25 years old, he was a gunner in the 16th Field Regiment and my mother, 19, worked in a small, family noodle restaurant. My mother had a privileged upbringing as a child. My grandfather was an engineering officer in the Japanese Imperial Navy and my grandmother the daughter of a local doctor, both from highly respected samurai families.

Their idyllic life was brought to a sudden halt with World War II. My grandfather died when his destroyer was struck by a torpedo from an American submarine in the Celebes Sea when my mother was 12, which left my grandmother to pack up her five children and move to a small town where her sisters lived. Two years after that, on August 6, 1945, my mother witnessed the atomic bombing of Hiroshima city from her sewing classroom at school. What followed has haunted our family ever since.

My mother and her classmates were quickly mobilised to take emergency supplies into Hiroshima city, so they set out on the long walk from their town, towing a laden cart. As they got closer to the city, zombie-like victims of the bombing came walking towards them. When they arrived at what they thought was the train station, it was unrecognisable. My mother left her schoolmates and trekked through the treacherous city to try to locate family living there but had no luck.

Later, she returned to the city again this time with my grandmother, only to find one relative who only survived a few more days. Not knowing what she had been touching or breathing in, many years after, Mum developed leukaemia. My grandmother died of stomach cancer in 1986 and to this day I believe they were linked to their horrific experience and the lethal effects of the radioactive substances they encountered.

It was not the done thing for my mother to have married outside her class, let alone a foreigner, but war changes everything. My father visited my grandmother and convinced her to allow her only daughter to marry him. After a convoluted military process, my parents finally married, and in 1952, my oldest brother was born.

Eventually, Dad returned to New Zealand to set up life in Hawke’s Bay, and my mother and brother followed him in January 1956. Over the next dozen years, they added to their family, with two more boys, then three girls, with my younger sister and I coming along several years after the first four.

I was born in 1966, the Year of the Fire Horse, or hinouma. Mum always led me to believe that was a good thing, until I found out it wasn’t. I understand we’re husband killers which would explain the exceptionally low birth rate that year in Japan as there was no point in having a daughter if you couldn’t marry her off.

My first contact with my mother’s family happened when I was about four, when her youngest brother came to visit us. To this day I am still trying to remember where he stayed as we lived in a tiny two-and-a-half-bedroom house - my three brothers were relegated to extra rooms outside as we got older.

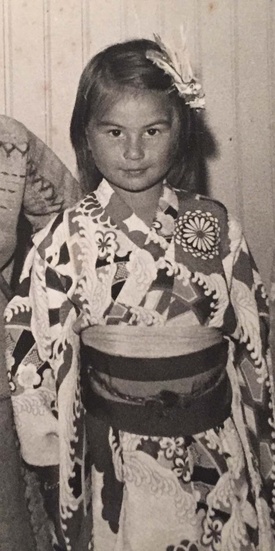

Growing up, I was always aware of my Japanese identity but as I was born in the days when speaking anything other than English was vehemently discouraged by the education community here, I was denied learning my mother’s tongue. But I would use chopsticks, say “itadakimasu”, and dress up in kimono for any fancy-dress reason. The half-Japanese boy in my year and I would also swap lunches, my cheese and jam sandwiches for his obento. I always wanted obento for lunch but by the time I came along, Mum was used to making sandwiches and not always with the fillings I liked.

In 1974, my Obāchan came to stay. She couldn’t speak a word of English and I had no Japanese with which to communicate with her. She used to spoil us with bits of beautiful rock candy. Whenever I see rock candy now, it reminds me of her. She grew marigolds and to this day the windblown seeds still sprout their orange faces in the most random of places on my mother’s property, so I feel like she’s still around when I see them.

Mum’s first trip back to Japan was at the end of 1978, 22 years after she had left, and my lucky younger sister and I went too because we travelled on a child’s fare. I was so unbelievably excited because I’d never been on a big plane before let alone go overseas. I am certain that my life has ended up the way it has because of that trip. We travelled on shinkansen to Hiroshima and met my mother’s brothers and their families and spent valuable time with my Obāchan. I was so completely dazzled by everything I saw and everything we did and ate.

On my return, I started learning languages. I started with French then moved on to German, but I really wanted to learn Japanese. I petitioned my high school, reasoning that mum had been a Japanese teacher and could support my studies via Correspondence School, but that was flatly rejected. However, I was really determined so when I went off to university, I announced to the world that I was going to study Japanese. What I didn’t count on was how hard it was.

I felt absolute shame that I couldn’t speak, read, or write Japanese, and struggled with learning the script, making sense of the grammar, and not being as good as some of the other students. I would send letters home to Mum, trying out my newly gained skills only to have them returned to me with red pen marking her corrections. I applied for holiday work in Japan only to be rejected for looking “too Japanese”. I think they were being kind about my poor language skills as I was so hesitant to speak, but it still hurt. I drifted and finally dropped out with my degree only halfway completed.

While at university, I discovered the rules around gaining Japanese citizenship had changed, from only children of Japanese fathers being eligible to children of either Japanese parent. I think I was the first in New Zealand to apply and receive my Japanese citizenship this way, but a few years later I was required to relinquish my New Zealand citizenship if I wanted to retain my Japanese one. So, I renounced my New Zealand citizenship. To this day I live in New Zealand as a permanent resident even though I was born and raised here, but it means that I can freely move and live between both countries.

In 1992, I met my former husband at a party in Auckland and after a whirlwind romance during which he accepted a place in the JET Programme, we married and headed to Hiroshima. My grandmother had died many years earlier so during this time I got to know the rest of my mother’s family really well. Her youngest brother whom I’d met first when I was four, gave us the most amazing experiences and I learned so much. I decided to re-enrol in my degree and chipped away at my language papers, but this time there was a purpose and a context to my learning. I took up shodō or calligraphy which greatly improved my kanji knowledge. In 1995, my daughter was born and as a response to not having one myself, I gave her a Japanese middle name.

Eight months after her birth, we returned to live in Dunedin, New Zealand, where I took a job at the University of Otago. I also became involved in the local sister-city group which eventually led us to return to Japan to live, this time in Hokkaidō. My son was born here, during a blizzard.

My language really came along, and I completed my long overdue degree in Japanese. I had become the first child in my family able to fluently speak, read, and write Japanese, and to live in Japan. In fact, in my wider Japanese community family connections, I think I am the only one to have achieved this. It was very hard work with a lot of tears of frustration, but I feel sadness that I’m the only one in my family to have had this experience and to have picked up the knowledge and skills to be able to keep that link alive between us and our Japanese family. I decided to retrain as a secondary school teacher where I taught Japanese and became the president of the New Zealand Association of Japanese Language Teachers. This was a good way to close the circle of disappointment that lingered from my own high school days.

These days I live with my 90-year-old mother, supporting her so she can remain living at home. We talk a lot about her life and my head is filled with the stories and experiences she has shared with me. I feel quite privileged to have been born into the family I have.

© 2021 Jacqueline Yoshioka-Braid