And I meant to ask you before, was your mother working before you left for camp in Riverside?

She was my dad's receptionist at his office because, you know, he couldn't really afford he was just building up his practice. And so she answered the phone, made appointments and stuff like that. So she went to work every day and we had a housekeeper or a maid look after us.

[Holly] If you're looking for vivid details, remember when we went to Manzanar you talked about the rations? They would give you so much butter that you would put it in the garden.

[Leland] Oh yeah. That was in Texas in Crystal City. That's where all of the doctors and the lawyers and the educated were sent with their families. That was their backup card just in case the U.S. lost the war. So we could say, “Oh, they gave us everything we nesded and then some.” They gave us butter. During the war, butter was scarce — it all went to the military. Canned goods, couldn't get canned goods over here.

And here, you go to anybody's house in camp down there and we find dozens of gallon canned fruit lined up under the bed because the people who ran the stores said to take it because if you don't take it, they're going to cut our rations. And it was the same way with the meat. They said go take this, we got to sell this.

And they had minted special money for us just for camp use. Every family got an allowance to buy whatever we wanted using these coins.

We didn't eat that much butter, but you're allowed so much every week. And it got so bad that my folks had a little vegetable garden behind our house. It was a duplex and grew green beans, china peas. I forgot what else, but just a small garden. He went out in the middle of the night and he says he got a bunch of butter and dug holes and buried butter all along the vegetables. And a couple of weeks later, they're all dying. But my dad didn't figure. He said, "I forgot they had salt in it."

So he inadvertently killed the whole garden.

Yeah, killed the whole garden because of the salt [laughs].

So what else about living there do you remember? Was your father working in Crystal City?

Yeah, he was a dentist for the people in camp. He was supervised by an army dentist. He was more like a figurehead overseeing the operation at the hospital.

But your dad was doing all the work.

Yeah. But my dad will say hey, if the war had come 20 years later, he would have welcomed it because he only worked from nine to five, no emergencies, no Sundays. It was like a picnic.

So you were in Crystal City when the war ended. Do you remember anything about when you know it was ending and you heard that Japan had lost the war?

Not really. I don't remember too much about the end of the war either.

So when you returned back home, how was the reception when you came back home?

Well, I don't remember too much interaction we had with the people living there. We had some good friends that came to visit us once in a while, but that's about it. Just my neighbor there. She was some case. Our property backed up to the Santa Ana River, which was dry most of the time. And she said that the reason we bought that property was because the submarines that could come from the ocean up to the Santa Ana River.

She had way too much time on her hands.

Oh, she had way too much time. Talk about ignorant. She was, really.

Was she by herself?

She was living there with her husband and son and her son went into the Navy.

[Holly] One interesting thing about their return is your neighbors had rented out your house, right? So for the first few days when they returned, his family had to sleep in the chicken coop because the family was still in their house.

[Leland}: Yeah, we had to clean up a chicken coop so we could have some place to stay while they moved out of the house. But it was, you know, a chicken coop was the chicken coop. It's really dirty. Had to go in there and take out the straws and all the shit [laughs].

What else do you remember about returning to school after this time and going back to school?

I was in junior high school and there was no incident I can remember there. Just going to school.

Did your father open his practice again?

Yeah, he went back to his office. It was all ready and went back there.

Wow. So did he have that until he retired?

Yeah.

[Holly] And didn't your mom end up going back to school?

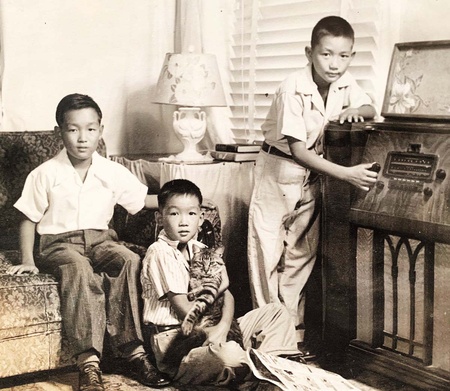

[Leland]: Yeah. And then after that, I see my mom was not the kind of like to clean house, do the laundry, she had filled up to here with that because she had three boys in diapers at one time. And this was way before they had disposable diapers. She had to do laundry every day. It was not an option.

[Holly]: Can you imagine that? And then having your husband taken away. Being left on your own, she had to be so strong. But she eventually went back and became an optometrist.

[Leland]: Yeah. After the war they were all in junior high school she says. And I said like I said, she didn't like housecleaning, dusting, doing laundry and all the stuff. She says I would rather go back to work and hire somebody to do that. So that's what she did. She went back to school and school was hard to get into because the war ended and all guys were getting free education. So it was just it was the competition to get into college was fierce, really fierce.

Anyway, she did really good. She graduated cum laude from optometry college. But mainly she got away from housekeeping and we hired a full time housekeeper.

Wow. She was very driven, ambitious.

Well, no, she just didn't like housekeeping [laughs]. She says, “I can make enough money that we can hire somebody to live there day and night, take care of everything I don't like to do.”

I love that that was her motive. That couldn't have been easy to go through school.

It was tough, yeah. Because she still had to keep the house in order, do the shopping. She still had to do the cooking most of the time. My dad loved to cook, so that would make a little bit easier on him. She'd come home on weekends and cook a couple of meals and put them in the freezer.

Years after the war ended, did your parents ever talk to you about how they felt during this time and about your father being taken away?

No. They didn't have any animosity or anger about that. It's just hey, it's life.

[Holly]: I find that sort of remarkable, like dad seems so, “It happened.”

If you had to guess how your parents felt and having this war break out between these two countries, could you now looking back have any sense of what they might have been feeling?

[Leland]: I really don't know. But I think the main thing is that they had themselves had nothing to do with the problem between the two countries. There's nothing you can do to promote or diminish it. It's out of your hands. It's almost like God's will. So I think that's the way they pretty much looked at it. What can we do? We didn't cause it, we can't correct it. They didn't say anything about it.

[Holly]: I think Mark and I are more outraged, you know what I mean? A generation later we're like, wait a minute. But I was always sort of struck by Dad's lack of resentment, you know, which I think is actually kind of sweet and probably powerful so that you don't get stuck in that anger. They just moved on. You have to move on, right?

And I'm curious, do you feel that its impacted your sense of self or the way you see the world?

No, no, I don't think so.

* This article was originally published in Tessaku on June 17, 2021.

© 2021 Emiko Tsuchida