For the most part, existing biographies of Ronald Lane Latimer’s life concentrate on Latimer’s publishing work and his relationship to Modernist poets like Stevens. Less is known of Latimer’s wartime activities and his postwar life. While Reverend Latimer’s defense of Buddhism in his statement before Tolan Committee has been recorded by various scholars, the story of his activism among Japanese Americans during the incarceration process remains much less known.

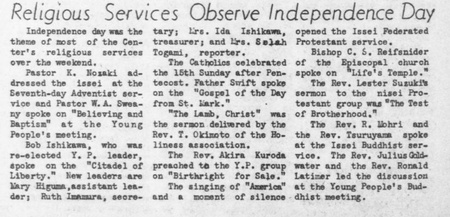

From April until late July 1942, Latimer, along with fellow Buddhist priest Reverend Julius Goldwater, made weekly trips on Sundays to the Santa Anita detention center to deliver sermons, lead meetings, and organize community events with the Young Buddhist’s Association. On April 18, 1942, Latimer made his first visits to Santa Anita to help organize a Hana Matsuri festival with Reverends Goldwater, Ishiura, and Kubose. Often, the sermons delivered by Reverend Latimer took place around major holidays such as Independence Day, and carried a patriotic message. The anthropologist Dr. Tamie Tsuchiyama recorded the work of Reverend Latimer in her report on the Santa Anita detention center, noting in particular that while “listening to Rev. Latimer’s sermons it occurred to me that in spirit American Buddhism has a less pessimistic tone than that of Japan, emphasis on love having replaced that on compassion.”

Around the time of the closure of Santa Anita detention center, Ronald Latimer attempted to enlist in the U.S. Army, but was turned down for service. He then returned to New York City, where he worked with the War Relocation Authority’s resettlement office. In fall 1943, Latimer relocated to an artist’s colony in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he was joined by former Poston incarceree Harley Oka in establishing a Buddhist center called “Dharma House.” At the same time, Latimer, along with Reverends Goldwater and Gyomay Kubose, served on the board of the Chicago Buddhist Church, and remained a member of the Buddhist Brotherhood of America.

Whether Latimer visited the Santa Fe Internment Camp, where a number of Buddhist priests were detained, is unknown. What is known is that during this time Latimer made multiple visits to the WRA camps. On October 2, 1943, the Heart Mountain Sentinel reported the arrival of Reverend Ronald Latimer for a week-long stay at Heart Mountain, where he had been invited by his former mentor Reverend Nyogen Senzaki. While at Heart Mountain, Latimer delivered a lecture on the conditions of life for Nisei on the East Coast, urging Nisei to leave the camps and stating that attitudes towards Japanese Americans in cities like New York were significantly more positive than before.

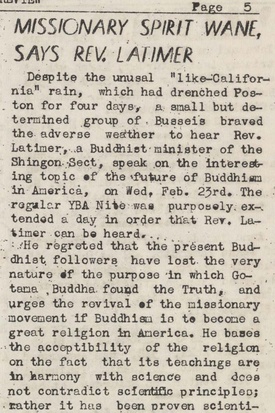

On February 24, 1944, the Poston Chronicle reported that Latimer had visited the Poston concentration camp the previous day, and had met with fellow Buddhist priest Shozen Yasui and delivered a lecture to the Young Buddhist Association. The Young Buddhist Association’s Bussei Review for Poston Camp III summarized his speech, highlighting Latimer’s call for a revival of Buddhism in the United States, following the egalitarian principles associated with Buddhism and self-determination according to the teachings of the Buddha, and Latimer’s own decision to convert from Catholicism to Buddhism in search of an alternative authority besides God.

After the end of World War II, Ronald Lane Latimer largely disappeared from view. The last likely mention of Latimer in the Japanese American press appeared in a February 2, 1946 article of the Rafu Shimpo that advertised a talk he gave at San Francisco’s Koyasan Temple. No references to a Reverend Latimer exist in the records of the Koyasan Temple in Los Angeles.

According to Ruth Graham and writer Alan M. Klein, Latimer led an eventful life in the postwar years, becoming an Episcopal priest and moving around to New Jersey, Santa Fe, and Florida. Sometime in the late 1940s, Latimer trained to become an Episcopal priest at the Church Divinity School in Berkeley, California. After briefly serving as a rector at an Episcopal church in south Florida, Latimer relocated to New Jersey in 1951, where he served as rector for a number of churches in Haddenfield and Helmetta and worked occasionally as a substitute teacher.

In September 1958, Latimer and his then “adopted son” Charles—whom they assume to have been his life partner—bought a house in Santa Fe and quit their jobs in New Jersey on the spot. Charles took up a job as a French and English teacher at Los Alamos High School. Ronald Lane Latimer found work as an art critic for the Santa Fe newspaper The New Mexican Sun, writing a weekly column titled “About the Arts,” and featured comments from Charles.

In January 1959, local papers announced that the Heart Sunday Committee, a local chapter of the New Mexico Heart Association, had nominated Reverend Latimer as chairman. The nomination presented one of the few detailed biographies of Latimer’s life, noting his earlier work on Alcestis Quarterly and his work with Wallace Stevens. Latimer also briefly alluded to his own prewar career as a Buddhist priest in his art column for The New Mexican Sun. In his October 25, 1959 column, Latimer highlighted the growing popularity of Zen Buddhism among the Beatniks, and praised the rise of Japanese culture in postwar United States.

Latimer’s stay in Santa Fe, however, was short-lived. In May 1960, Los Alamos High School decided not to renew Charles Latimer’s contract as a teacher. When Charles and Ronald Latimer directly asked the principal, James Shattuck, at a school board meeting about renewing the contract, Shattuck made a “slanderous remark” toward Charles. Although journalists did not record the remark for ethical reasons, the remark is likely to have been a homophobic slur. In response, Ronald, Charles, and former teacher Evelyn Bennett sued Shattuck for slander, a suit which lasted two years. By 1962, Ronald Lane Latimer and Charles were recorded as living in Sarasota, Florida, where Latimer worked as an Episcopal priest. Two years later, on December 19, 1964, Ronald Lane Latimer died at the age of 55. Although the local Sarasota Herald-Tribune claimed that Latimer had “succumbed while conducting a service alone,” scholar Al Filreis argues it is more likely that Latimer took his own life.

The story of Ronald Lane Latimer is one shrouded in mystery. To this day, literary scholars continue to debate the contributions of Latimer to the American literary canon, especially his close relationship with Wallace Stevens. Most of Latimer’s correspondence is now preserved with his literary associates is preserved at the University of Chicago special collections, and his letters continue to appear in books on Wallace Stevens and the Modernist movement. Yet Latimer’s advocacy on behalf of Japanese Americans and Buddhism, as brief as it was, is nonetheless memorable. Even as the history of American Buddhism is now becoming more known thanks to Reverend Duncan Ryūken Williams’s 2019 book American Sutra, we can also see how even in 1942, priests like Latimer saw Buddhism as a part of the fabric of American religious life.

Yet Latimer’s life also could be descried as erratic, a quality that likely stemmed from many factors. From this point of view, Latimer’s statement to the Tolan Committee is revealing: “I wrote to General DeWitt asking for permission to go with my people. I want to go with them, yes, emphatically, under any conditions.” The sense of finding “my people,” or achieving a sense of community, can be a seen as a theme that dominated Latimer’s life, especially as a bisexual man isolated within a homophobic society. His desire to work with Japanese Americans, and his defense of the community against outside prejudice, reflected his own commitment to push against the barriers he himself had experienced.

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen