Some years ago, I had a chance to spend a month doing extended research in the rare books and manuscripts collections of the Houghton Library at Harvard University. It was there that I came across the typescript diaries of William R. Castle, a leading American diplomat and public figure, the entries of which provided me with quite interesting and instructive material on Castle’s ideas.1

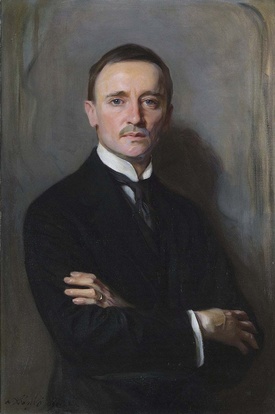

William Richards Castle, Jr. was born to an elite American family in the kingdom of Hawaii—his grandfather founded the renowned Castle & Cooke company. He attended Punahou School and then Harvard University. In 1919, Castle joined the United States State Department, and rose eventually to the level of Under Secretary of State in 1931.

In 1929 Castle was appointed interim Ambassador to Japan by President Herbert Hoover (the choice rested less on his diplomatic skill than his personal fortune, which allowed him to maintain the costly US embassy in Tokyo). Throughout the 1930s he remained an advocate of peaceful engagement with Japan, and an admirer of Japanese culture.

In the period before Pearl Harbor, he was a central backer of the isolationist America First Committee, and testified before Congress against the Lend-Lease Act. In the years after 1945, he served as president of Garfield Memorial Hospital in Washington DC.

According to the Houghton Library’s description, William R. Castle’s diaries “contain an almost daily account of Castle's professional and social activities, and include comments on national and international affairs, the political scene, books, and movies.” Indeed, the entries, at least those covering the World War II era, reveal the thoughts of a bitter conservative critic of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal. Castle relates his discussions with friends and allies such as Chief Justice Harlan Stone, aviator Charles Lindbergh, and former president Herbert Hoover. Even John F. Kennedy, then a young Navy Lieutenant, makes a few appearances.

In addition, one thing Castle's diary entries powerfully reveal is his belief in the racial inferiority of African Americans and his strenuous opposition to equal rights for them. Still, his principal vituperation in relation to the “race question” is reserved for a single figure: Eleanor Roosevelt. Castle repeatedly vilifies the First Lady for her interference in social relations and for motivating blacks to act in arrogant fashion (Castle uses a slur similar to “uppity”). In fact, Castle seems to have made it his business to record in his diary the racist jokes he heard about Mrs. Roosevelt, as well as repeating outrageous stories about her supposed immorality and use of her public position for personal gain.

The diaries are likewise laced with anti-Semitic slurs. Castle repeatedly presents Jews as unpleasant people incapable of acting in the public interest. He particularly deplores what he considers Jewish influence in the Roosevelt administration, with Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter serving as the purported shadowy (and foreign) Jewish figure controlling the government. Oddly—possibly revealingly—even as he airs without reserve his feelings regarding Jews (couched at times in offensive language), Castle does not seem to consider himself an anti-Semite, and in fact he deplores the actions of “Jew haters.”

The reason that all this is of interest to the historian, other than giving an unvarnished picture of the ideas and beliefs of some elite white Americans of the wartime period, is that alongside his negative feelings about Blacks and Jews, Castle expresses warm feelings in his diary about the Japanese people and about Japanese Americans, especially those from his native Hawaii. Furthermore, his diary records his efforts to assist them in the face of widespread discrimination against them.

To begin with, in early February 1942 Castle offers sympathy to Ryo Arai [the son of Yoneo Arai, a Harvard-educated banker] who is having difficulty enlisting in the U.S. Army Air Force. Castle lauds him as a typical American boy but suspects that he will have trouble getting into military service, and will have a difficult time even if he does enlist, all because of his Japanese face. Soon after, Castle notes that he has heard again from Ryo Arai, who has been turned down by the War Department because of his Japanese ancestry. [In the end, Ryo Arai enlisted in the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) during 1942, and served in Southeast Asia during World War II]. Castle also records shortly afterwards that he has read an excellent article on Japan sent to him by its author Clarke Kawakami, the Hapa Nisei journalist who also later worked for the MIS.

In April 1942, Castle recounts a conversation with Colonel Thomas Spaulding and David Crawford of the University of Hawaii. Crawford deplores the official treatment of [West Coast] Japanese Americans, with authorities making no effort to separate the loyal from the disloyal. Castle says that the worst of it is that the Nisei are fervently loyal to the United States, more so than other Americans, and would even be ready to volunteer for a suicide squad if required. He adds that when he was Ambassador to Japan, he spoke to many Japanese Americans at the Embassy, and he was impressed by their outspoken patriotism.

Castle says that he hopes to help set up a media campaign to persuade newspaper columnists and radio commentators to praise the loyalty of Japanese Americans. He has the idea of contacting President Felix Morley of Haverford College (himself a leading prewar isolationist) to help with the campaign. Three months later, Castle recounts a dinner with Spaulding, who is still eager to help Japanese Americans. He reports with pleasure that Felix Morley has been trying to get scholarships for Japanese Americans and that Spaulding has been making similar efforts at the University of Michigan, his alma mater.

While Castle speaks no more of such efforts at assistance over the year that follows, in December 1943 he reports that he has been visited by Ned Lewis, who wishes to discuss the formation of a committee to look after and direct the many Nisei resettlers who are coming to work in Washington DC. Castle recounts that he is noncommittal about joining the proposed committee but glad to offer whatever help he can give.

Similarly, in August 1944, Castle reports on a meeting with an unnamed man who is responsible for running the organization to assist the newcomers. They have found a house on Washington Circle which they intend to transform into a hostel. Castle finds the man humane and sensible and repeats that he is ready to help their efforts, provided they avoid any sentimentality.

He repeats this warning in October 1944, when he hosts the new Japanese Relocation Committee for a meeting at his house. For example, while Castle favors the creation of the hostel, he insists that it should be put on a self-supporting basis as soon as possible—presumably it will be more respectable if it is not a public charge.

In late October 1944, Castle reports that he and his wife have been invited to a party at Fellowship House, where they spoke to a number of Nisei. Castle notes that it really feels like being in Japan for him, except that the Nisei do not have the same manners as their forebears. He says that he enjoyed the party, but was troubled by worries over the fate of the Nisei in American society, and whether they could be successfully integrated. He indicates that the question is whether interracial marriage could solve the “Japanese problem” but does not state his own view.

Castle adds that at the party he was pleased to meet Japanese American soldiers from Hawaii based in nearby camps. A few days later, he reports approvingly a visitor’s report that the Japanese American soldiers have been the freest from disciplinary action of all the American Expeditionary Force.

In February 1945, Castle reports that he attended a hearing of the community “War Chest” to decide allocation of local charity funds. Castle explains that he was there in support of funds to run the hostel for Japanese American resettlers for the coming year. Castle says that in his own testimony, he recommended that unless such financing was against the War Chest policy, it should be granted, if only to reward Japanese Americans for their patriotism and loyalty. However, he tells his diary that he doubts whether the money will be awarded, even though those advocating for it spoke well.

A March 1945 entry concerns a director at the Garfield Hospital who visits Castle and asks whether the hospital should hire more Nisei clerks, since they already have several, and also whether they should take on a dietician who is well-recommended. Castle replies that he should hire the clerk but not the dietician. The reason for this, he says, is that there is too much opposition to Japanese Americans by patients, and if there were any accident with spoiled food or food poisoning, the dietician would be surely blamed.

In an entry from April 1945, at the time of the United Nations Conference, Castle comments that there are many high-quality “Germans” and “Japanese” in the country who should be used in any postwar occupation of Axis countries.

William Castle’s diary entries remind us that Japanese Americans, even in the months after Executive Order 9066, still had important supporters. Castle admired the character and patriotism of the Nisei, some of whom were personal friends. Despite his horror of “sentimentality,” he was willing to help resettlers in Washington DC and even to lobby for community funds for their support. The fact that Castle, who showed such real concern and empathy in regard to Japanese Americans, was also so markedly hostile towards Blacks and Jews reminds us of the complexity of racial/ethnic dynamics.

Note:

1. It should be noted that the original gift of the diaries to the Houghton Library restricts use of their contents. The Library may permit paraphrasing of the entries, but only the Castle family may authorize any actual citation. While it is unclear whether this restriction still stands, I have decided not to make any direct quotes from the diaries here.

© 2021 Greg Robinson