In my previous article for Discover Nikkei, I uncovered the wartime newspaper coverage of the incarceration of Japanese Americans in the French press. In postwar France, the retelling of Japanese American history offers both a vivid example of foreign interest in United States history and a window into French views towards race and society. Studying the presentation of United States history abroad provides both a commentary on American issues abroad and an extra scope for understanding other people’s investment in historical narratives.

It should be noted that, even before World War II, the French people have long been intrigued by the topic of Japanese migration to the United States. By the turn of the 20th century, in tandem with an overall French fascination with Japanese culture, French writers began commenting on the growing population of Japanese immigrants in the United States and the issues raised by their presence. Author and Japanologist Louis Aubert discussed in his 1908 book Américains et Japonais the rise of “Yellow Peril” hatred in the United States and Canada, describing both movements for restriction of Japanese immigration in both countries, and their position within U.S. racial hierarchies. Several other books appeared in France in the following years. Yet after Jean Pajus’s doctoral thesis, published in the USA in 1937 as The Real Japanese California, the literature from France on Japanese Americans largely disappeared for the rest of the 20th century (Pajus taught economics at UC Berkeley at the time, and to this day a scholarship exists in his name for exchanges between Berkeley and French universities). French newspapers likewise scantly reported on Japanese American issues, though the Redress movement of the 1980s garnered a small amount of attention.

Rather, arguably the most visible and most-reported point of contact between Japanese Americans and France was the French commemoration of the Japanese American soldiers of the 442nd RCT. During the postwar years, several French communities commemorated their liberation by the Nisei soldiers, notably the town of Bruyères, where the 442nd had faced its greatest challenge.

The JACL maintained connections with the town of Bruyères as part of efforts to memorialize the soldiers of the 442nd. On October 30, 1947, the town of Bruyères installed a plaque gifted by the JACL as part of a monument to the soldiers of the 442nd that died in rescuing the Lost Battalion. In March 1948, the JACL sent 51 care packages to the town of Bruyères as a token of gratitude for the town’s help in constructing the memorial for the 442nd. Mayor Louis Gillon, a former resistance fighter, personally wrote to JACL president Hito Okada to thank him for the gifts. A year later in October 1949, The Pacific Citizens reported a large ceremony organized by the French military commemorating the courage of the 442nd, and noted the town’s invitation of former Nisei soldiers to make a pilgrimage to Bruyères.

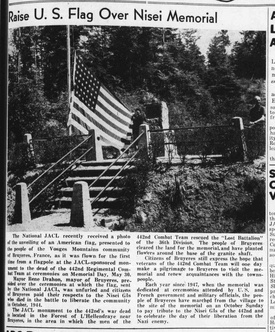

In August 1952, The Pacific Citizen printed photographs of a flag ceremony at the monument in Bruyères dedicated to the 442nd. The National JACL, which had helped sponsor the monument, sent an American flag, which citizens of the town unfurled yearly on Memorial Day, even as its residents expressed hopes of seeing their former liberators again. In 1961, the French newspaper Le Monde reported on a sister city ceremony between Bruyères and Honolulu, although the paper incorrectly identified the 100th Battalion as the “Texas battalion” and the 442nd as a “regiment formed of Hawaiians.” In 1994, the Netherlands-based Japanese American artist Shinkichi Tajiri, himself a 442nd veteran, dedicated in Bruyères his sculpture The Friendship Knot to the friendship between the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the people of Bruyères.

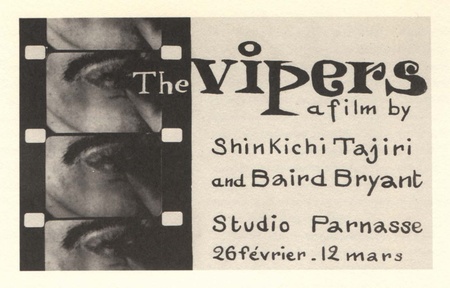

Several Japanese Americans established themselves in France during this period. The aforementioned Shinkichi Tajiri, although more known for his work in the Netherlands, originally began his artistic career in Paris in 1948 studying on the GI Bill, and became a protégée of French painter Ferdinand Léger and sculptor Ossip Zadkine. In 1955, Tajiri produced a short film titled The Vipers with Baird Bryant. The experimental film depicted Shinkichi, his wife Ferdi, and Baird and his girlfriend together smoking marijuana - a humorous response to Reefer Madness. According to his autobiography, Autobiographical Notations, Tajiri started the project after a Japanese Hawaiian sculptor loaned him a Kodak 16mm camera and told him to make a film. He decided to create a film that displayed the ritual of rolling a joint interspersed with images of getting high. The film was nominated for the Cannes Film Festival that year and received the Golden Lion Award for “Best Use of Film Language.”

Other Nisei such as Steve Wada and John Yoshinaga also studied in Paris. Fellow 442nd veteran and civil rights activist Robert Chino lived in France after the war, where his extended family remains to this day. And although not an American, Japanese-born artist Tsuguharu Foujita, who had been a renowned public figure in 1920s Paris and then worked briefly in the United States during the 1930s, returned to France after World War II, took the name Léonard and designed the Notre Dame de la Paix chapel in the French city of Reims (it is still colloquially known as the “chapelle Foujita”).

In the postwar years, a number of Japanese American soldiers were also stationed in France. Famed journalist and writer Gene Oishi recounts in his memoirs In Search of Hiroshi of his time stationed in the French village of Verdun, the site of the World War I battle, where he played the trombone with the soldier's band at various local nightclubs.

Yet at the national level, news coverage of the wartime incarceration would not reemerge until the late 1990s. By the early 2000s, French newspapers had begun to reference the internment of Japanese Americans - as part of what Bruno Rochette, in a 2004 review of Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine in Le Monde Diplomatique – as a “hidden” or “forgotten” history.

Often the references to the camps in these articles provided additional context to current issues in the United States, such as the restriction of civil liberties after 9/11. For example, in 2019, following the release of the AMC show The Terror: Infamy and in the wake of reports on the Trump Administration’s policy towards immigration, the radio program France Culture presented a program on the camps and the work of Miné Okubo, noting in particular the issues facing Japanese Americans resettling after leaving the camps.

Likewise, when Japanese American members of Congress protested the Islamaphobic language of Trump in 2019, Le Monde used the occasion to recount the history of Manzanar. In 2020, Le Monde and La Croix each reported on the apology issued by the California State Assembly towards the Japanese American community.

Films presented an alternative medium for discussing the Japanese American experience. Alan Parker’s 1989 film Come See the Paradise, while a box-office bomb in the U.S., received critical acclaim in European countries like France and received a nomination for the Palme d’Or at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival. In 2002 the Franco-German TV channel Arte screened Emiko Omori’s film Rabbit in the Moon, a film inspired in part by the work of French filmmaker Chris Marker.

Most revealing, though, is the life story of filmmaker Marcel Ophuls and his encounters with the incarceration. Originally born in Saarbrücken, Germany, as the Jewish son of filmmaker Max Ophuls, Marcel and his family fled Germany and France following the rise of Nazism and fall of France. Settling in Los Angeles in 1941, the young Marcel Ophuls went to high school with a number of Japanese Americans. He recalled in an interview with Studs Terkel the moments following Executive Order 9066 and forced removal:

“When I made movies – like The Sorrow and the Pity – about the behavior of ordinary people in crisis situations, one of the things that kept me from being too self-righteous is my memory of the Japanese kids who were in my class one day and gone the next. I have absolutely no recollection of protesting or questioning. I wasn’t a six-year-old child. I was fourteen, fifteen at the time. Why didn’t I react with more sensitivity? So, in my films, I can’t be a prosecutor or a hanging judge.”

The moment later inspired his film The Sorrow and the Pity, which documented the response of ordinary French citizens to the Holocaust and French collaboration with Nazi occupiers in the roundup of Jewish communities.

As with film, books on the wartime experience of Japanese Americans have also captured French audiences. In 1997, David Guterson’s novel Snow Falling on Cedars about the trial of a Japanese American man was translated into French. Miné Okubo’s book Citizen 13660, titled Citoyenne 13660, was translated into French in 2006. And, more recently, the French publishing house Les Éditions du Sonneur published Anne-Sylvie Homassel's translation of John Okada's No No Boy with help from U.S. journalist, filmmaker, and Okada scholar Frank Abe.

Despite the attention given to the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans, most French commentaries hesitate, unlike Ophuls, to compare it with examples from French history. Although French journalists and authors report on U.S. race relations and racism, discussions of racism in France are silenced by French officials because, according to sociologist Jean Beaman, discussing racism contravenes the republican values of equality conferred through citizenship. Arguably there are parallels to be made with French imperial history, such as the description of France’s actions during the Algerian War as “hidden” or “forgotten” history and the longstanding tensions over Muslim populations in France. Yet such connections with U.S. history, and the history of Japanese Americans, are yet to be seen.

*For more information on the European newspaper coverage of the Redress movement, see Jonathan van Harmelen's article “Lessons from a Different Shore: Portrayals of Japanese American Incarceration and the Redress Movement by Western European Newspapers” as featured in the Fall 2021 issue of the Journal of Transnational American Studies.

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen