Booker T. Washington, Marcus Garvey, and Jitsuzo Harada in Chicago

Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, founded by Booker T. Washington in 1887, was well-known by certain Japanese because “Japanese who had read Up from Slavery in translation saw in Tuskegee methods one of the means of overcoming their nation’s technological lag behind the West” and Tuskegee was “a mecca for not only Africans but West Indians and Asians.”1 The first Japanese student at Tuskegee, who enrolled “as part of a national movement to become ‘westernized,’”2 was Iwana Kawahara of Tokyo. Kawahara first arrived at Tuskegee in 1906 and graduated in 1908. Washington’s internationalism also brought to Tuskegee numerous Indian students who had escaped British rule at the turn of the twentieth century,3 offering opportunities to connect with other internationalists such as Marcus Garvey and the Black Dragon Society, who were interested in world race politics.

A Jamaican radical activist, Marcus Garvey “viewed himself more as a disciple of Washington.”4 In return, Washington respected Garvey’s determination to set up a school in Jamaica.5 On the other hand, certain Japanese felt an affinity for Garvey, as his slogan, “Africa for Africans,” was mirrored in the Black Dragon Society's motto, “Asia for Asiatics.” Generally speaking, the Japanese public agreed with those slogans and the sentiments that they embodied. For example, several Japanese in New York were rumored to have attended meetings of Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association and even made speeches there6. In Los Angeles, Japanese businessmen “declared that the Oriental people desire the cooperation of the other Colored races and that the University of Japan, situated at Tokyo, and other Japanese institutions, are desirous of trading students with any Race institution in the country in order that the two races may become better acquainted with each other.”7

Another member of the international circle at Tuskegee was Lajpat Rai, who visited the campus in 1907.8 Laipat Rai was a leader of the Indian nationalist movement who visited Japan in 1915 and in July 1920, he contributed an article to the Asian Review, an English language journal published by the Black Dragon Society.9 His article, which was written in the epistolary form, or in the style of a letter, was entitled “Appeal of Indian Exile in the U.S. to Lloyd George, British Minister” and published in Japanese in Ajia Jiron, a publication of the Black Dragon Society.10

The relationship between Booker T. Washington and his Japanese admirers was actually rather cordial. Washington was interested enough in learning more about the Japanese that he responded to journalist, Naoichi Masaoka, who asked Washington to write the preface for his book on America. In 1912, Washington wrote to Masaoka in Tokyo that “the wonderful progress of the Japanese people and their sudden rise to the position of one of the great nations of the world has nowhere been studied with greater interest or enthusiasm than by the Negroes of America.”11

In appreciation of his interest and support, the Japanese consul in Seattle hosted a reception for Washington when he visited the West Coast in 1913, with four hundred local Japanese in attendance, and offered to sponsor a scholarship to Tuskegee Institute.12 At the same time, though, Washington discovered on this trip that Japanese and African Americans in cities on the West Coast were competing for jobs as waiters and hotel workers. Washington observed that “the Japanese are steady, reliable, sober and always on the job.”13

In Chicago, where the Chicago Tuskegee Club was founded in 1911,14 Harry Jituzo Harada was so interested in Booker T. Washington that he wrote him a letter in October 1913, asking for his opinion on racism toward the Japanese and restrictions on Japanese immigration.15 Harada was born in April 1888 in Osaka, came to the U.S. as student in November 1905,16 and arrived in Chicago around 1912. While maintaining a carefree, single life as a student and domestic servant,17 he wrote for various media. He was “an editor of the Middle-Western Japanese Year Book for 1914, published by the Japanese Christian Association in Chicago,” and an editor “of the Hokuto Sei (North Star), a bi-weekly review of literature and current events published in Japanese.”18 He was also a Chicago correspondent for the Japanese vernacular newspaper, the Nichibei Shuho in New York, and wrote articles about the African American community for this publication.19 He traveled in the South in 1918 to collect information for a book he was writing about African Americans, and his travel reports were published as a series in the Nichibei Shuho newspaper.20 He was one of the more interesting Chicago Japanese, and was naturalized in Chicago in December 1955 when he was sixty-eight years old.

Let us return to Garvey. By the time of Booker T. Washington’s death in 1915, Garvey had learned from Washington “the ideals of economic solidarity, self-sufficiency, educational development and race conscious pride.”21 Garvey “originally came to New York City in 1916 to raise money for a school in Jamaica that would be modeled on Washington’s Tuskegee Institute.”22 Meanwhile, Garvey used “the methods of Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee to uplift darker people of the world”23 and placed Tuskegee in “the framework for more radical forms of pan-Africanism and Black nationalism.”24

Garvey came to Chicago only once, in the fall of 1919, “to promote his dream of a black Utopia on the continent of Africa, and galvanized the community with his message of racial independence.”25 The purpose of Garvey’s visit was to sell shares of stock in his new project, the Black Star Steamship Company, and to verbally attack Robert Abbot, founder of the Chicago Defender, who had criticized Garvey in the newspaper, in a public address. However, Garvey was not given a chance to make the speech, as he was arrested in front of his audience “on charges of violating Illinois’s blue-sky law, which regulated the sale of stocks and bonds,” “based on evidence (given) by a black private investigator in Abbot’s employ.”26 He was “fined $100 and costs” but finally his “company was licensed to do business under the laws of Illinois on October 22, 1919.”27 Unfortunately, Garvey never returned to Chicago after his release.28 Furthermore, Abbot intensified his animosity towards Garvey by indicating that he was “ready to cooperate with [the FBI] office on all investigations pertaining to Negro radical activities.”29

Takeo Shinichi Nosho

By the time Garvey came to visit Chicago in 1919, there had already been various radical African Americans who claimed solidarity with Japanese for social justice. For example, the International Peace and Brotherly Love Movement, advanced by Rabbi David Ben Itzoch, a Black Jew, called for participation in the movement for the betterment of humanity to all kinds of Jews, not only white and Black, but also “the Chinese Jew, the Japanese Jew and the red Jew.”30 “Jonah,” also known as “Jonah the preacher,” was a white missionary whose real name was Rupert Griffith, He demanded that “the Jim Crow schools and cars must be removed” and that “if the U.S. does not change its attitude in the next five years, (black Americans) will create a dangerous friendship for the Japanese. The friendship for the darker races of Mexico and South America will become a natural unification cemented with another race and Japan is quick to see the importance of this coalition.”31

Just before Garvey’s Chicago visit, an advertisement soliciting contributions to the World’s League (233 West 137th Street, New York) appeared in the April 5, 1919 Chicago Defender. In the advertisement, Dr. R. D. Jonas, an international organizer of the League, “claims that the Japanese are willing to finance the company to carry on a shipping trade between New York, Egypt and Liberia,”based on “information received from the Japanese ambassadors and representatives of high authority in that country.”

In this atmosphere of pro-Japan sentiment growing in some parts of Chicago's African American community, there lived a Japanese man who was likely influenced by the internationalist circles of certain African Americans and the Black Dragon Society. This man was Sinichi Nosho, who was born in March 1881 in Japan and employed as a pharmacist at Victor & Nosho Chemist Co., located at 3171 Ellis Ave.32 The earliest record of him of his life in Chicago is a 1915 letter that he wrote to a doctor in San Francisco for a Japanese patient that he had seen in Chicago, Yuji Nishi. However, instead of going to San Francisco to see the doctor, Nishi went to New York City, fell from a window at a Chinese restaurant, and died there.33 But from this letter we know that Nosho had established himself in Chicago before 1915.

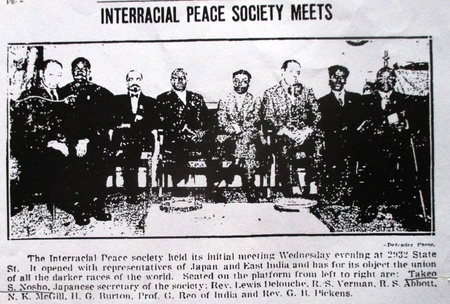

In 1926, Nosho served as the secretary of a newly organized institution, The Interracial Peace Society, which was located at 2932 State Street in Chicago. The goal of the Society was to unify the non-European, darker races of the world, as internationalists such as Marcus Garvey and the Black Dragon Society were advocating for. The society was reported to have 600 followers, and among the attendees at its first meeting, there were two representatives from India (R. S. Verman and Professor G. Reo from the University of Bombay,) other African Americans (including R. S. Abbott, editor and publisher of the Chicago Defender,) and Nosho.34 We must wonder what brought Asian Indians, Japanese and African Americans together in Chicago, and why a Japanese person was assigned to be the secretary of a group that was founded by the African American community. Perhaps it was because Nosho actually initiated the group, and could thus easily assume a leadership role.

Furthermore, it is peculiar that Asian Indians would have attended the meeting unless they were deeply committed to the objective, a kind of Pan-Asianism that the Black Dragon Society had advocated. The 1920 census showed that there were a few Asian Indians living in Chicago, but they were counted together with Filipinos, Koreans, Hawaiians, Malay, Siamese, Samoans, and Maoris for a total of 231. Abbott, founder of the Chicago Defender who was already collaborating with FBI, may have been there to spy on the meetings. While internationalism was rising in popularity among Chicago's African Americans, a new black town named Liberia was planned for establishment, just east of Joliet (southwest of Chicago) and opening ceremonies were scheduled for July 17, 1925.35

As the relationship between the U.S. and Japan worsened in the late 1920s, Japanese attitudes toward African Americans shifted; what had once been a genuine interest became a self-centered, nationalistic attitude largely influenced by a political desire to shame American society and discredit the United States. For example, on December 15, 1919, headlines such as “American’s Massacre of Black People”and “Corpses Filled in a River” led an article in the Maeli Sinbo, a journalistic organ of the Japanese colonial government in Korea, and achieved its goal of influencing its readers. As a result, Japanese attitudes toward African Americans became distorted and completely removed from reality.36

Notes:

1. Harlan, Louis R, Booker T Washington, page 276.

2. McClure, Brian, Educating the Globe: Foreign Students and Cultural Exchange at Tuskegee Institute, 1898-1935, page 179.

3. Ibid.

4. McClure, page 131.

5. Ibid, page 129.

6. Nichibei Jiho, September 5, 1925.

7. Chicago Defender, December 3, 1921.

8. McClure, page 199.

9. The Asian Review, July 1920 page 564.

10. Ajia Jiron, December 1917.

11. Booker T. Washington Papers, Vol 12, page 84.

12. Chicago Defender, March 29, 1913.

13. Chicago Defender, April 5, 1913.

14. Booker T. Washington Papers Vol 13 Page 92.

15. Ibid, Vol 12 Page 328-329.

16. Washington, Passenger and Crew Lists.

17. WWI registration, 1920 census, 1930 census, WWII registration.

18. Booker T. Washington Papers Vol 12 Page 328-329 .

19. Nichibei Shuho, January 19, 1918.

20. Nichibei Shuho, May 11, 1918.

21. McClure, page 131.

22. Michaeli, page123-124.

23. McClure, page vi.

24. McClure, page vi.

25. Michaeli, page 123.

26. Ibid, page 125.

27. Chicago Tribune, June 23, 1920.

28. Michaeli, page 125.

29. Michaeli, page 126.

30. Chicago Defender, August 23, 1913.

31. Chicago Defender, January 22, 1916.

32. WWI registration, 1920 census.

33. Nichibei Shuho, May 22, 1915.

34. Chicago Defender, February 6, 1926.

35. Chicago History, Summer 1975, Page 120.

36. Sato, Hiroko, “Kawamura Tadao cho American Negro no Kenkyu Shokai”, Tokyo Women’s University Kiyo No. 39, page 66.

© 2021 Takako Day