Sociologist Tadao Kawamura and the University of Chicago

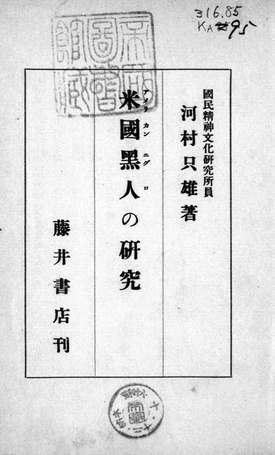

It is not known at this point whether Harry Jitsuzo Harada (the journalist who wrote to Booker T. Washington asking his opinion about Japanese immigration on December 15, 1919) ever completed his book on African Americans, but Tadao Kawamura actually did. Kawamura was a sociologist trained at the University of Chicago and his book, American Negro no Kenkyu (Research on American Negros) was considered the first Japanese book on African Americans that was professionally researched and written before the war.1 However, it is interesting that the book was not published until 1942, after Kawamura’s death in 1941.

Tadao Kawamura, born in Yamaguchi in 1893 and a 1920 graduate of Doshisha University School of Theology, came to Chicago in 1922 and enrolled in the junior class of the Chicago Theological Seminary.2 Many Doshisha graduates had attended Chicago Theological Seminary in the past, and, according to Kawamura, those Japanese graduates of the Seminary would become “the most active elements in the Japanese Congregational Church.”3

Although Kawamura was once tempted to attend Oberlin Seminary in Ohio with one of his friends, he stayed in Chicago and called the Chicago Seminary “my home.”4 At the same time, he attended classes at the University of Chicago's Department of Sociology, starting in the autumn quarter of 1922.5 He eventually earned an MA from the graduate Divinity School in August 1924 with a thesis titled “The Social Significance of the Horizontal Movement in Japan”6 and a PhD in sociology and anthropology in spring 1928 with a thesis titled “The Class Conflict in Japan as Affected by the Expansion of Japanese Industry and Trade.”7

At this point it is not clearly known whether Kawamura was ever a student of Robert Ezra Park, a “commonly considered central figure of Chicago Sociology”8 and professor at the University of Chicago, or if Kawamura somehow helped with Park’s 1924-25 Pacific Coast Survey, gathering life-history stories from Japanese immigrants in order to “reveal the mind of the Oriental to the American.”9 But we do know that after enjoying campus life as president of the Japanese Students’ Association10 and attending a national conference held at Princeton University as the Chicago representative of the Japanese Student Christian Association in 1926,11 Kawamura went back to Japan in 1928. He returned to Chicago in May 1929 as a staff member of the Japanese Student Investigation section of the Ministry of Education.12 Later, he was appointed research director of sociology at Kokumin Seishin Bunka Kenkyusho (Government Research Institute of National Culture.)13 He translated John Dewey’s essays, Impressions of Soviet Russia, and Robert Lowie’s Primitive Society into Japaneseand published them in 1930 and 1939 respectively.

Kawamura's thesis topic, class conflict, hints at his personal perspective towards Chicago's African American community. Hiroko Sato, who compared Kawamura’s book, American Negro no Kenkyu, withother Japanese scholars’ writings on African Americans, argued that Kawamura’s unique strength was his academic focus on Scott Nearing, a socialist/communist/radical activist who had been in the spotlight since the 1910s, who other Japanese scholars scarcely paid any attention.14 Was Kawamura’s attachment to Nearing somehow related to Kawamura’s Christian background, in the same way that early Japanese Christians were drawn to socialism in the beginning of the late 19th century?

In fact, Kawamura’s American Negro no Kenkyu wasn't an original work, it was a translated, abridged, edited and expanded version of Scott Nearing’s Black America, based on Nearing's writing but adding his own opinions and interpretations of African Americans history and culture, and his experiences in Chicago. For example, Kawamura's contributions included a long history of African Americans that included President Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, a section titled “Negros’ Cries at the Washington Naval Conference,” and detailed definitions of the National Association of Advancement of Colored People, the National Urban League, and the Commission of Interracial Corporation. Adding to Nearing’s description of the lives of African Americans living in Chicago's Southside, Kawamura commented, “This is the destiny that the U.S., which claims to be the number one country in the world, provides for its citizens.”15 Furthermore, he included an appendix on the history of Native Americans, which was not in Nearing’s book. Although it is not known why Kawamura added Native American history to his book on African Americans, he may have felt some sense of responsibility and owed an explanation to his Japanese readers when Nearing claimed in Black America: “the ruling class of the United States has come into intimate contact with two ‘different’ peoples; the American Indians and the Negros. Indian culture has been practically exterminated. The Indians that resisted the process are dead.”16

As president of the Japanese Club at the University of Chicago in 1926,17 Kawamura must have had some contact with African Americans in his daily life. His observations and ideas, which were based on his personal experience, emphasized the connection between Japanese and African Americans based on their shared experiences as “oppressed races” in the U.S. For example, he once befriended an African American waiter on a train from San Francisco and heard about this waiter’s life over the next few days. He learned that the waiter on the train was a college graduate and held a law degree from a respectable university in the Midwest, but could not find a job at his educational level.18 The experience led him to write about the extreme racial discrimination that African Americans faced finding employment, despite their education. With this example in mind, Kawamura observed that Japanese students also experienced similar discrimination when they looked for summer jobs in order to pay tuition.19

Was the following passage drawn from Kawamura’s own observation at the University of Chicago? In a chapter on educational discrimination, he wrote: “The chairs on both sides of a negro are empty, because white students don’t want to sit next to a negro. It is because of body odor. Racial discrimination is related to body odor. Japanese have a specific odor as Japanese. I remember that one of my American friends told me that Japanese stink. But Americans also stink to the Japanese.”20 Nearing did write about educational discrimination in his book,21 but he did not include these kinds of crude observations as examples.

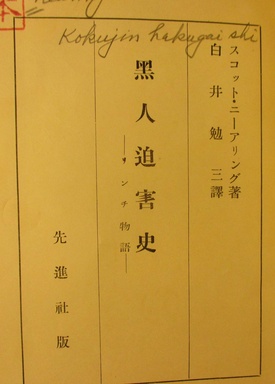

Although American Negro no Kenkyu was not published until after Kawamura’s death in 1942, his translation of Scott Nearing’s Black America, or Kokujin Hakugai-shi: Rinchi Monogatari (History of Black Oppression: Lynch Story) was published in 1931 under the pen name of Benzo Shirai. Shirai (aka Kawamura) was faithful in his translation to Nearing's original text except for a few interesting additions, including a list of books and publication cited. He also included six photos and a list of important facts from Nearing’s book, which American Negro no Kenkyu did not include. Kokujin Hakugai-shi: Rinchi Monogatari included two additional photos of the 1919 Chicago race riot, taken by Chicago Evening Post photographer Jun Fujita, accompanied by original captions by Shirai/Kawamura. Shirai/Kawamura also added text to the photo captions from the original book that he republished in Kokujin Hakugai-shi. . For example, to the photo that was originally captioned “White mob exulting over its dead victim. Burned to death in Mississippi,” Shirai added “ladies are laughing at the sight of the burned body of the victim;” and for the photo captioned “the mob enjoys the gruesome spectacle to the end, Waco, Texas,” he added that “White were watching the scene as if they were in a vaudeville theater.” Those editorial changes hint at Kawamura’s personal feelings toward African Americans.

Nearing ended Black America with a statement of hope for the future of human society, stating that “Emancipation for the American Negro, as for any other subject race under the capitalist imperialist system, can come only when Negro working masses have joined the white working masses in smashing the economic and social structure built upon individual and race exploitation, and by replacing it with a cooperative economic system under working-class control.”22 Shirai translated this paragraph and published it in Kokujin Hakugai-shi: Rinchi Monogatari. In comparison, Kawamura’s American Negro no Kenkyu skipped an entire segment of Part III, or “The Negro Struggle for Freedom” of Nearing’s Black America, in which he expressed his hope that socialism would help African Americans in their struggle for equality. Why this omission? And why did Kawamura use a pen name in the first place?

After Kawamura returned to Japan in 1928, he worked for the Japanese government, specifically in the Ministry of Education, investigating problems among students. He may not have felt at liberty to publish his sympathies and inclination towards socialism, and this may be why he had to use a pen name for his translation of Nearing’s book and delete its last chapter in American Negro no Kenkyu. Hiroko Sato argues that Kawamura’s goal in writing and publishing American Negro no Kenkyu wasnot to expose the “shame” of America, but simply because he believed in the future of the African American movement.23 Then, was the last chapter deleted by somebody else? The book’s preface, written by Enkichi Ito of Japan's Ministry of Education and Tadayoshi Kihara, a philosopher, emphasized the importance of the book's publication during World War II, as it exposed the harsh core of America's racist society, and Ito believed that the book would emphasize the importance of the Japanese imperialist motto of Hakko Ichiu, or all the world under one roof.24 Furthermore, the book's postscript ended with a statement claiming that America should not spread its philosophies to the world until its negro problems were resolved.25 Was this postscript written by someone other than Kawamura?

Although it is not known whether delaying publication of American Negro no Kenkyu until after his death was his decision or not, the fact that Kawamura did not see the book in print while he was alive may prove to be the ultimate expression of his scholarly consciousness as a sociologist. Did he delay publication because he predicted how the book would be interpreted in Japan’s political climate?

After the Immigration Act was signed by President Coolidge in May 1924, effectively ending Japanese immigration to the U.S., the Chicago Defender published an article titled “Exclusion Bill Should Teach Japanese Lesson.”26 The article, showed some sympathy by saying “We feel sorry as American citizens that Congress felt it necessary… to put this insult upon a proud and worthy people,”but the editor also criticized the Japanese by writing that “the Japs, like some of us, have been too busy courting the favor of the white man” and that “perhaps this will be a lesson to the proud Japanese to watch his white brother a little more closely and show more sympathy to his other dark skinned relatives.”

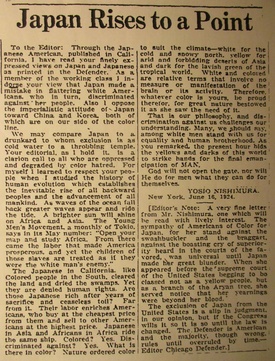

Yoshio Nishimura, a Japanese communist in New York who was a close comrade of Sen Katayama, responded to the Chicago Defender article as follows: “As a member of the working class I endorse your view that Japan made a mistake in flattering white Americans … Also I oppose the imperialistic attitude of Japan toward China and Korea, both of which are on our side of the color line…. Whatever color is yours, be proud therefor, … the present hour bids the yellows and darks of this world to strike hands for the final emancipation of MAN.”27

“Whatever color is yours, be proud therefor” reads as a form of self-identifying colorblind pride in the pursuit of the “emancipation of MAN” that enables Nishimura and others to get beyond differences in political ideologies and still take a stand against racism. In 1942, a similar tone of voice was heard in the Chicago Defender, this time from conservative assimilationist, Samuel Ichiye (S. I.) Hayakawa, a Canadian Japanese Nisei who “repeatedly expressed a determination not to be limited or pigeonholed by his Japanese background” and who “opposed ethnic-based organizations on principle.”28

Notes:

1. Sato, Hiroko, “Kawamura Tadao cho American Negro no Kenkyu Shokai”, Tokyo Women’s University Kiyo No. 39, page 66.

2. Chicago Theological Seminary Annual Catalogue, Sixty-Fifth Academic Year 1922-1923

3. Kawamura, Tadao, “The Stranger within the Gates”, Chicago Theological Seminary Register January 1925 Vol XV No1

4. Ibid

5. University Registrar, personal correspondence with University of Chicago Library Special Collection

6. University of Chicago Convocation Programs August 29, 1924

7. University of Chicago Convocation Programs March 20, 1928

8. Persons, Stow, Ethnic Studies at Chicago 1905-45, page 45

9. Ibid page 68

10. Cap & Gown, 1926

11. Shin Sekai, September 13, 1926

12. Shimadzu, Misaki, List of Visitors to the US Chicago Japanese YMCA

13. University of Chicago magazine, Vol 31, No7, April 1939

14. Sato, page 70

15. Kawamura, Tadao, American Negro no Kenkyu, page 106

16. Nearing, Scott, Black America, page 6

17. Daily Maroon, March 10, 1926

18. Kawamura, page 75

19. Ibid

20. Ibid, page 85

21. Nearing, page 176

22. Ibid, page 262

23. Sato, page 71

24. Kawamura, page 2-3

25. Kawamura,page 201

26. Chicago Defender, May 31, 1924

27. Chicago Defender, June 21, 1924

28. Robinson, Greg, The Great Unknown, page 291

© 2021 Takako Day