“I had it in my backpack. I couldn’t wash it. Okaasan collected 1,000 stitches at Tule Lake from 1,000 different women, one stitch for one. If you were born in the Year of Tiger, you can stitch as many as you want because tigers are strong and it’s good luck.”

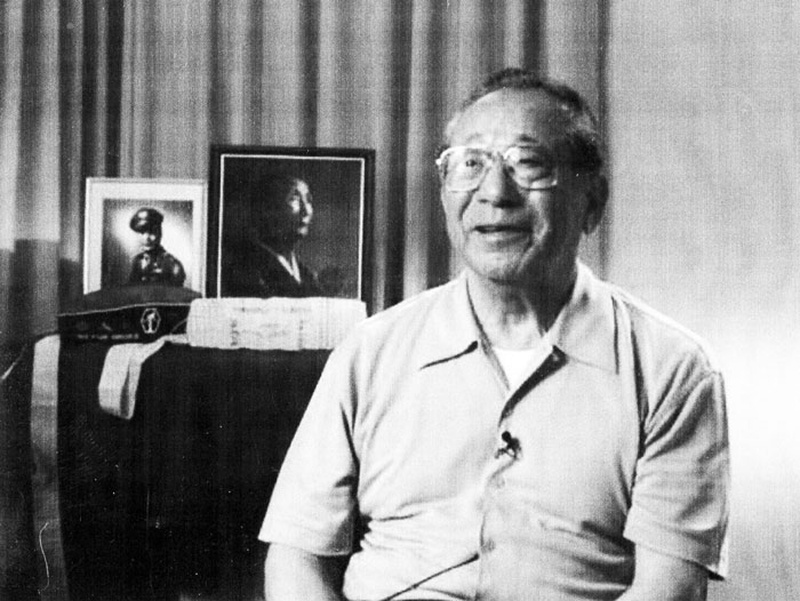

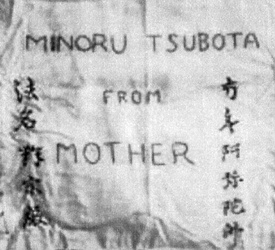

Min Tsubota, a 442nd Regimental Combat Team veteran, was showing his 60-year-old “senninbari,” a long sash with 1,000 stitches. Though it has a few small stains, it still looks almost brand-new; it is made of a rice sack. He thinks life must have been particularly hard at the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, California, where there was a major conflict between the Yes-Yes and No-No Boys.

Min explains about the sash.

“That’s a mother’s love. She never told me (she was doing this). I never asked. I thought about it afterward.”

Min was born in Kent in 1918, the youngest of ten children. His parents came from Hiroshima in 1901. His father, Sentaro, had a sawmill in Kent to make railroad ties for domestic use and sometimes shipped them to Japan. His mother’s given name was Fusano.

Min volunteered for the army in March 1941. He had basic training at Camp Roberts, California, and was then sent to Camp San Luis Obispo to join its 40th Infantry Division. There, he became a member of the 160th Army band, playing the saxophone that he had kept since high school.

“There were professional musicians from Hollywood. Studio and big dance-band musicians volunteered for the California National Guard because at that time, they were exempt from the draft. But 3,4,5 months later, the army activated them and they became the 160th Infantry Regimental Band. I was lucky to have met and played with professional musicians from all parts of the US.”

Meanwhile, the war broke out, and Min’s family was sent to the Tule Lake camp. In January 1942, the 40th Infantry Division which included the 160th Regiment, received orders to the South Pacific Theatre of Operations with specific orders that no soldiers of Japanese ancestry would accompany them. Min and 185 other Nikkei soldiers from the 40th Division were immediately transferred and assigned to Reception Center, Fort Bliss, Texas, near El Paso. The group left Los Angeles by train about 3 AM with MPs (military police) stationed at each end of the rail car and with blinds pulled so that they would not be observed.

However, it turned out that Min could use his Japanese ancestry and bilingual skill at Fort Bliss where he worked at the headquarters. He became an interpreter for a general court-martial for the wrongful deaths of two Issei shot at the Lordsburg internment camp, New Mexico.

When the war broke out, the FBI already had a list of teachers, kaicho (leader types), and other important persons to pick up. The fishing industry was on its list because boats had radios on them. Immediately, they picked up two fishermen, even though one’s back was bent from being crushed between boats and the other had TB. Together with 132 other Issei from the Fort Missoula, Montana internment camp, they were shipped to Lordsburg.

In September, the court-martial proceedings were held at Fort Bliss where 23 Issei witnesses came forward. The prosecution tried to prove that the two victims were too sick to run but the MP guarding them said they were killed because they started to run away.

“I interpreted for them. I felt bad but we couldn’t prove at the trial (that they couldn’t run). Nobody else was there to witness the incident.”

Meanwhile, Min received a letter from his mother in Tule Lake telling him to be sure to visit a cousin living in Utah.

“I went to visit him and met Cherrie. The cousin was married to her older sister.”

Min and Cherrie couldn’t see each other, so they just exchanged letters until Min was transferred to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, to join the 442nd RCT. He proposed to her and they were married in March 1943.

“She came all the way across the United States, to St. Louis, then to Jackson, Mississippi. I am so grateful. She came all the way alone in a train packed with strangers, the only Asian.”

His mother, wishing him a safe return, asked the 1,000 ladies to help her make the traditional senninbari sash and sent it to Min before he was shipped overseas.

Assigned to the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, Min departed Hampton Roads, Virginia in May 1944, leaving a three-day-old daughter and beloved wife behind. The large convoy carrying 101 ships zigzagged across the Atlantic Ocean. It took 30-31 days to get to Brindisi, Italy.

In August 1944, Min was wounded. He describes the battle as “the most frightening moment of my life” when Germans fired at them south of Florence, Italy. His comrades tried to hide in the opening of a big water drainage pipe but he was unable to do so.

“They fired a first time, a second time, and the next one will be on target!”

Min knew the procedure too well and that gave him a fright.

“I was so scared that my whole body could crawl into my helmet. And when I thought I would die, I remembered my childhood, my mother, my father just like a movie.”

Sure enough, the third shell exploded near him and shrapnel went through his back.

“I had a dozen letters from Cherrie in my back pockets. The shrapnel went through the letters but I was saved.” Cherrie’s letters acted as a shield.

“Without it, it could have gone to the vital organs. I really think that Cherrie’s letters and my mother’s senninbari saved me,” said Min. Recognizing the support from these two beloved women, he smiled radiantly.

In August 1945, the 522nd reached the concentration camp in Dachau, Germany and saw all the Jewish bodies piled up in a boxcar.

“There are some people who say that that didn’t exist (the Holocaust) but we were there. We saw it,” says Min.

They were ordered not to give any food to the Jews because they were too weak and frail from hunger.

“We were helping Jewish people there but at home, my mother and all other Japanese were interned. I felt it was ironic.”

Min came back on December 24, 1945 and was discharged in March 1946 from Ft. Douglas, Utah.

“Some people asked, ‘How did you greet your mother when you came back?’ But you know Issei — even between oyako (parents and kids), we don’t embrace. She was just happy that I came back, just held my hands, her tears running down.”

Min’s mother passed away in 1977.

“When I think back, I feel like I should have embraced her.”

His reminiscences and his love for her never die.

Min was asked to join the Military Intelligence Service to go to Japan but his family was too important to him. He decided to leave the army.

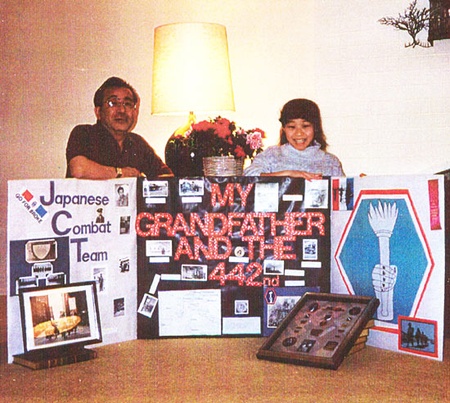

Several years ago, his granddaughter, Karen, a middle school student from Mercer Island, did a presentation about her grandpa and the 442nd.

“I didn’t know anything about this. She did it all on her own. She was so proud.”

And Min is so proud of her, too. Min also remains quietly proud of Cherrie, who went all the way across the country to marry him and who raised their baby while he was on duty. The love Min’s kind heart received from his mother carries on from generation to generation. The power of a mother’s senninbari is as strong as the ocean’s current, invisible beneath the ripples.

*This article was originally published in The North American Post-Northwest Nikkei on February 28, 2004. The North American Post recently edited and republished it on their website on July 11, 2021.

© 2004 Mikiko Amagai