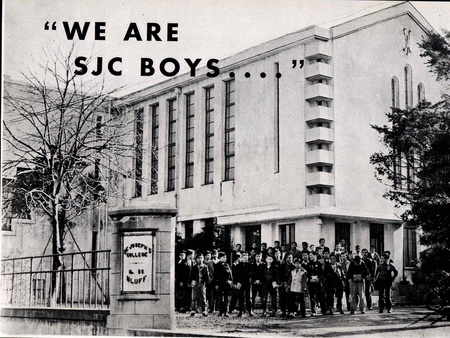

My move from the boonies of Shikoku to the Tokyo-Yokohama area took place in 1950 after I graduated from Japanese middle school (shinsei chugakko). My father rented a house in Hiyoshi, Kohoku-ku, Yokohama; Keio University was just beyond the tracks. Sakuragicho, the end of the Toyoko Line, was a forty-minute ride away and from there I got on a streetcar to take me to Motomachi. I climbed the long steps up the bluff to get to St. Joseph College.

I had arrived in the area in between school years and so I had to wait until 1951 to enter. I was already eighteen. And the Korean War had started. It was an uneasy year of waiting—but the shoe didn’t drop. I was not drafted, although my draft status was 1-A. Fortunately, I was overseas and the long arm of Uncle Sam did not reach me. So I spent the idle time getting acclimated to big city life.

The only other time I was in such surroundings was when I was growing up in the Los Angeles area as a child. That all changed when WWII broke out and we were uprooted to be dumped into concentration camps with my father arrested by the FBI for having access to a fishing vessel that could be used to contact nonexistent enemy submarines. He was placed in different detention centers throughout the United States.

Big city life in Tokyo included packed commuter trains, black market bazaars, movie theaters, eateries…a culture shock of the western and eastern customs and habits. The Tokyo/Yokohama area was home to the balanced chaos that was the result of the cultural crosscurrents finding an equilibrium. The Meiji Era ethos of embracing everything western which was impelled by the American presence in postwar Japan was alive and well: the people embraced the change, except for the nationalistic right-wing elements on one hand and the communists on the other. There were protests and clashes between the two. But all in all, life progressed along the lines established by SCAP under General Douglas MacArthur and the Japanese enjoyed the growth of a fledgling democracy.

All the verities that informed the western mind were transplanted on Japanese soil with the result of a hit-or-miss process of assimilation. Christian missionaries flooded the devastated land to bring Christian faith and ideals to the people, but they could not compete with the local religions of Shintoism and Buddhism. Christians represent only 1-1.5% of the population today.

SCAP—Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers—established all the overall rules and regulations that governed the land until the signing of the peace treaty in 1952 which brought imperial Japan and the American Occupation to an end. Among the arrangements was the assignment of train coaches specifically for Occupation personnel and their dependents.

I, a displaced American lookalike, stood in the Japanese section, although I carried my Alien Registration Card, identifying me as an American citizen. I probably could have sat in luxury in the specially designated coaches but I didn’t want to raise a fuss, so I stood among the packed bodies of the other Japanese in envy—and in conflict with my identity. Was I a Japanese or American? I was an American, of course. But I was an American caught in terrible circumstances.

At one point, a group of foreign Caucasians entered the special coach and I knew just by looking at them that they could not be Americans. Their mannerisms gave them away. And I thought looks do matter. If you look like an American, you can pass as one, even though you were born Turkish, Italian, German, Portuguese. Where did that put me? I felt inferior, left out in the cold. But I persevered—in my own way. I began to focus on my self—that final touchstone of reality. And it’s been a long road to completion.

After many long months of idleness, I finally matriculated in St. Joseph College in the fall of 1951 as a junior. I felt that at long last I will get an education that would fit my needs which were not met during the war and afterwards in Japanese school. Before the war disrupted everything, I went up to the beginning of the fourth grade, and I didn’t learn a thing in the camps primarily because I had to leave class each day early to participate in a special diet program for invalids. My mother enrolled me in the program since I had a bad case of asthma.

My first day at school at St. Joe’s was marked by the smell of the polished halls. The smell struck me as institutional and it was then that I realized I had entered a realm where teaching took priority over the other petty pursuits in life. And I was bound and determined to study hard and perform for the teachers. I wanted to be an excellent student.

I was already nineteen, a year beyond the normal graduation, and I would be over twenty-one by the time I graduated from high school. There was only one other student who was older than I—a Japanese national. My father, who was not interested in education, delayed my schooling which did not take precedence in his thinking, but as I restlessly approached exiting my teens, he must have felt it was time for me to complete my basic education. So I was entrusted to the care of the Marianist Brothers who were dedicated teachers, strict but fair.

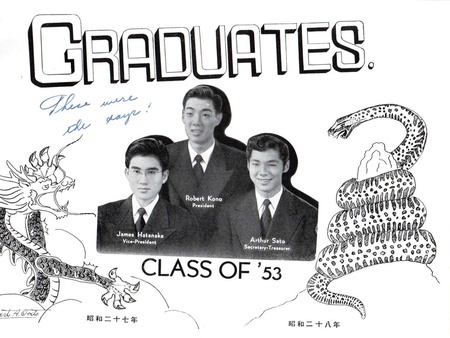

And I prospered as a student. I got good grades, in spite of the background commotion produced by my sick mother, forcing me to cover my ears as I concentrated on my studies. The lack of sleep, combined with my work at Ofuna Supply Depot as a night watchman, often made me late for class. But I survived to be elected senior class president in 1952.

My officers—vice president and secretary-treasurer—were both Nisei, a Japanese American and a Canadian Japanese. Mine was a Nikkei administration. And we thrived. I wound up with the highest grade point average and was selected the class valedictorian. In the meantime, I single-handedly wrote, directed, and acted in the school play that won first place in competition with the junior class. I say single-handed because no one else wanted to be part of the production: “It’s your idea, you do it.” So I got stuck with it. I’m glad to say it went well with my orchestrating the music and writing the lyrics of the song we sang as “The Three Cheers,” the title of the play.

We played softball, held school-wide track and field events, organized a crackerjack soccer team which repeatedly won the all-city championship. We formed debating teams, played fierce ping pong, went on school excursions. The one the senior class went on was to Takamatsu, Shikoku where I was able to use my knowledge of the local dialect, Shikoku-ben. We were forbidden from seeing certain movies but went anyway without being caught. We were also forbidden to smoke, and when someone did—usually in the john—he was severely reprimanded. After all, St. Joseph College was a Catholic boys school and the regimen was strict—but just…after a fashion. Some teachers resorted to corporeal punishment—with a ruler—which was always borne in silence.

My valedictorian speech was about God and country. As I was speaking, I was interrupted by an older alumni who corrected my pronunciation of a man’s name, and I made the adjustment as if nothing untoward had happened and continued on with my speech. Afterwards, a student who had graduated the previous year came up to me and asked: “How did you do it?” I just shrugged. I was on a roll—and nothing could stop me.

After I graduated in 1953, I went to Chapel Center in Tokyo one Sunday and was accosted by a man from CIA. I had belonged to the Chapel Teens for a number of years and was an officer of the group. He asked if I wasn’t interested in working for The Company. It was an opportunity to get out of the dead-end job I had with a foreign trading company, so I said, Yes. And I took a test to see if my translation skills were up to snuff and I passed and was given a hundred dollar salary in yen to work on the outside, translating sensitive documents. I couldn’t see myself working out of home, so I arranged to rent a room in a crowded Tokyo neighborhood disguised as a Japanese university student and worked on the outside for six months before I requested to come on board…a regular office job within CIA with a dollar salary and PX privileges.1

Several months passed. The slow bureaucratic wheels ground away. I wondered how CIA had heard of me to begin with. Was their reach so extensive and ubiquitous as to extend to the halls of learning at SJC and to the gatherings in church? I decided that it was indeed, that they could spread their interest into any corner of any institution or group they wanted. So began my association with the super secret organization.

Since I had to change my status from an alien national residing in Japan to a DAC (Department of Army Civilian), I was flown out of the country to Okinawa, an American territory in those days, and given a phony GS-9 grade to make my way back into the country as an important person. In actuality, I was given the grade of GS-4, the lowest grade possible, and paid an hourly wage. I had no contract, benefits, or pension. Thus began my career as a working stiff with CIA, a translator/interpreter at large, low man on the totem pole, with only a high school education whereas all the other Niseis had either college degrees or were veterans.

But I didn’t complain. How could I? We were penniless and destitute, with no prospects for the future. I needed to support my parents and that dollar-an-hour salary had to stretch. And I made it stretch by budgeting everything. No extravagances. And no debts. Running up a debt was anathema in my book. My father had lived a life of debt and I vowed to never be like him.

I turned out to be the jack-of-all-trades. Not only was I a translator/interpreter of highly sensitive material, but I was also a manager and errand boy working out of a mansion, a secret cover organization, that housed the overt part in the front of the building and the covert part in the rear separated by a single sliding door. I was the manager for the household staff which included three servants, a cook and a couple of Japanese guards stationed at the entrance. I served as a mail courier when the regular was incapacitated. All of that while maintaining high-quality translations and interpreting at high level meetings between Japanese government officials and ranking U.S. military personnel.

Although I was a mere translator, the kinds of documents that crossed my desk covered the entire scope of the U.S. presence in Asia. It gave me an overview, albeit piecemeal, of the entire functioning of U.S. intelligence as it applied primarily to the entrenchment of communism in Japan, Red China, and North Vietnam during the height of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. The experience turned me into a staunch anti-communist, even more of a one than before. I’ve always said: “Communism is unfit for human consumption.”

All in all, I can say that my experiences at St. Joseph College and CIA made me more cognizant of the concomitants of national security from the faith-based vision for our country to a resistance to communism. Our politics, economy, culture, and freedoms may be challenged but what must remain inviolate, under all circumstances, is our commitment to help one another, regardless of race or creed.

Note:

1. Post Exchange (US Army base retail store)

© 2021 Robert Kono