It is a commonplace that the presence and contributions of racial minorities have been too long and thoroughly erased from the writing of America’s history. Yet, as the eminent historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. once observed, if racial conflict has remained excluded from the nation’s consciousness, as expressed by the writing of history, then the repressed has returned in its unconscious, as represented by literature—classic American works by Twain, Melville and others are awash in feelings, fantasies and fears over racial difference, with nonwhite characters playing crucial roles in these narratives.

At a different level, the same split is true of Japanese American society. In the first half of the 20th century, newspaper editorials and essays in the English-language Nikkei press centered on the struggles of Japanese immigrants and their descendants to adapt to life in white American society. Blacks seldom appeared as subjects of news reports or editorials, and such references as existed were certainly not always positive (it would be revealing to do an analysis of the diverse uses of the “N-words” in the prewar Nisei press).

True, in the postwar years a small circle of progressive activists and intellectuals, led by Pacific Citizen editor Larry Tajiri, reminded their readers that anti-Nisei prejudice was but a by-product of the larger discrimination against African Americans, and underlined their duty to join intergroup struggles for civil rights. Yet when the first generations of chroniclers, from Bradford Smith and Bill Hosokawa to Yuji Ichioka and Ronald Takaki, came to write the history of Japanese Americans, they failed to discuss the rich history of Black-Nisei connections, and downplayed the role of African Americans and anti-black racism in shaping the group’s development as a minority community. Still, if African Americans have been largely absent from the conscious memory of the Nikkei over the last 100 years, they have remained a powerful presence in community writing.

Indeed, in symbolic terms Nisei literature can be said to have started with African Americans. The very first published novel by an American-born Japanese, Karl S. Nakagawa’s 1928 potboiler The Rendezvous of Mysteries, opens with the introduction of Jeff Jenkins, an “elongated colored gentleman.” Jenkins engages in a conversation with white magnate Lewis Dalton, his seatmate on a train bound for Sacramento. Nakagawa (whose novel did not feature any Japanese characters) presents Jenkins’s character as rather comic—a “queer duck” as Dalton refers to him. Nakagawa even uses touches of minstrel humor. For example, Jenkins explains, in crudely rendered dialect, that he was once a “pugilis’” but that he no longer boxed: “kissin’ the canvas had become my habit…so I jes’ quit the game of fisticuffs.”

He also proudly states that he eats “at leas’ three good meals of po’k chops a day”. In an extended scene in the middle of the book, he is staying alone in a haunted house, where he brings a pair of large watermelons to eat, but is frightened away by “spooks” (a plot point that anticipates the antics of the “Feets, don’t fail me now” school of comically frightened black servants portrayed by actors such as Stepin Fetchit and Mantan Moreland in 1930s Hollywood).

However, as it turns out, Jenkins is not altogether a stereotype. He soon comes to realize that he has been duped, and at the story’s climax he shows bravery and saves a white woman who has been captured by the villains. The book closes with Jenkins, who had previously declared himself to be a “wimmin hatah fo’ life,” being rewarded by romancing Dinah, a black housemaid. In view of these developments, a case could perhaps be made that Nakagawa’s initial depiction of Jenkins in clichéd fashion was a way to set up his readers for the later surprise.

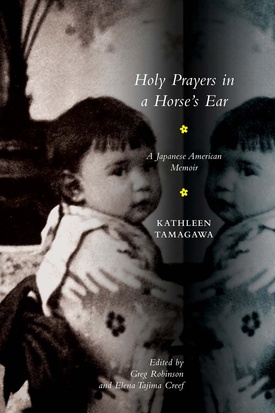

Another foundational piece of Japanese American literature, hapa Nisei writer Kathleen Tamagawa [Eldridge]’s 1932 memoir Holy Prayers in a Horse’s Ear, also references African Americans. Unlike Nakagawa, Tamagawa does not include any major black characters. Rather, her only black character with a speaking role is “old, fat Nan, the colored wash woman” who works for the family during the author’s girlhood in Chicago. When little Kathleen brings together a cat and dog and they quickly attack each other, Nan says, “Maybe cats and dogs don’t have no fights in Japan, but they sure do in the U-u-United States.”

For Tamagawa the phrase becomes a watchword of Americans’ cockeyed ideas of Japan, and their misidentification of her as Japanese. Such absurdity comes to a head years later, when the author is in a Southern hospital preparing to give birth. She hears an “animal-like cry.” The white head nurse is dismissive: “One of those half-n----r girls in the ward. It is her first baby. She has been going on like that for hours. You can hear her all over the place every time the door is opened.” Tamagawa asks whether anything can be done for her, and the nurse scoffs: “Oh, she’s alright. These n----rs make an awful ‘to-do’ about nothing.” The author understands that the nurse's bigotry is outrageous.

However, rather than challenge the obviously unfair treatment, she resolves to be silent, even at the cost of great pain: “No-one would ever say, 'It’s that Jap girl in room 31, making an awful ‘to-do’ about nothing.'” Tamagawa is so fixated on being "decent" that she makes no sound at all, leading the nurses to conclude that she has had a PAINLESS birth, something the nurses claimed was previously known only in the Orient! In sum, the author’s reward for letting herself be silenced by racism, even if she considers it absurd, is to be orientalized.

In the decade that followed publication of Tamagawa’s book, the young Nisei living in Western communities established a prolific literary culture. The English-language Nikkei press ran short stories and poems in Sunday literature pages and holiday editions, while Nisei litterateurs put out a handful of literary journals, including Reimei, Gyo-Sho, and Leaves. James Omura’s monthly magazine Current Life, established in 1940, published fiction as well. In their essays, many Nisei lauded the talent of African American writers, who had well expressed the same feeling of being a minority and the associated “double consciousness” that they experienced.

In a 1937 article, writer Yasuo Sasaki praised the work of such figures as Booker T. Washington. James Weldon Johnson, Countee Cullen, and Langston Hughes. “Will there ever be an Oyama or Koyama to merit mention in the same breath as these men? Will there ever be a Marmaduke Watanabe to blurt out in in fiery print words that come from the very depths of him, words like [those] by James Weldon Johnson, he of The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man?”

All the same, only a tiny number of short stories in the Nisei press referred to blacks or had African American characters. Those that did were a mixed bag, both in terms of the depth of their portrayals and their viewpoint. The anonymous sketch, "Zip-Biff-Pow," which ran in New World in 1933, was the grittiest. It describes an altercation between Black and Nisei youngsters on a San Francisco street corner —the Nisei insults the black boy by snarling the “N-words,” whereupon his victim hurls a racist epithet back at him. The two start brawling, and attract a crowd. Finally they are called on to stop by a “colored gentleman,” who reprimands them both in the name of interracial solidarity: "Shame on you two boys. I'm surprised to see you two nationalities fighting like this. The Japanese and the negro races should be dependent on each other. We need each other—we should be like father and son.” While it is unclear which race he intends should assume the paternal role, and which the filial, his wise diplomacy brings the boys to apologize, shake hands, and separate.

Another African American character is featured in the poignant story, "The Chocolate Killer," which appeared in Nichi Bei Shimbun in 1936. The sketch was part of a series of sports stories authored by sportswriter/journalist Vince Tajiri. It tells of a black man, Joe, who shines the narrator’s shoes. The narrator notices that Joe has “cauliflower ears” and deduces that he used to be a boxer. He learns that Joe, known as “The Chocolate Killer,” was once a successful fighter and a title contender, until a car accident led to the amputation of his leg, and the end of his career. A different kind of story of loss is Kenny Murase's "Resurrection," which ran in Kashu Mainichi in June 1939. Murase depicts a Nisei embittered by prejudice who tells his tale of woe to an African American bartender, then is shocked to discover that the bartender was a brilliant scientist who made a great discovery, only to be defrauded by racist whites out of the fortune that it produced.

At the other end of the spectrum is Ayako Noguchi’s “Highway 99,” which ran in Nichi Bei Shimbun in October 1939. The narrator describes a sedan with three oversized Black women, who stop off at a roadside stand to eat watermelon. The car pulls in, and “for awhile, we couldn’t even tell if there was anybody inside it or not. Black car, black occupants… whatta plight!” The women’s speech is rendered in dialect (à la “It sho am sweet”) and the author plays up their grotesque size. The whole piece seems to the current-day reader to reflect a storehouse of ugly racial clichés, a sense heightened by the appearance of a blackface illustration by artist Roy Kawamoto alongside the story.

One exceptional story from the 1930s was “Lady in a Bathrobe,” which was published under the name Wataru Mori (which may have been a pseudonym for the prolific Nisei writer Joe Oyama) and appeared in two parts in Rafu Shimpo in 1937. Told from the point of view of a Nisei boy, it describes his curiosity over the secretive woman in the house next door. “She was neither white nor black. Nor was she brown. Her color was of a creamish tinge that verged on light and dark.” The young Nisei is unable to understand why Miss Julie wears a bathrobe all day, why she is continually visited by both Black and white men, and why his mother describes her as a “bad woman.” Finally he accepts an invitation to join Caesar, a neighborhood black boy, in running errands for her. When he enters Miss Julie’s house, she is friendly to him and pays him well, but he feels unable to return because of his mother’s disapproval.

The story attracted an unprecedented level of reader comment—not for its portrayal of African Americans, but its morally ambiguous tone and daring sex worker subject. After a half-dozen readers complained, the second half of the story was postponed, only to be reinstated in expurgated form after more readers responded by asking to see the conclusion.

To be continued...>>

© 2022 Greg Robinson, Brian Niiya