In my previous article for Discover Nikkei, I described my trip to the UC Davis archive and my research into William Koda’s papers. As part of my article, I mentioned discovering a letter sent by attorney Leslie Gillen to the Koda family that discussed the potential effect of William Koda’s death upon the family’s claim case. As the largest claim ever filed by a Japanese American family under the Evacuation Claims Act of 1948, the story of their claim and the legal battles fought over it tell another story of tragedy and triumph.

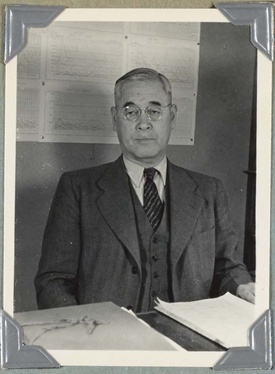

Although the hardships of the incarceration were incalculable for the mass of its victims, the Koda family likewise faced monumental financial losses. In August 1954, James M. Hanley, Jr., a representative of the Koda family, testified before the House Judiciary Committee as to the losses of the Koda family as a result of the incarceration.

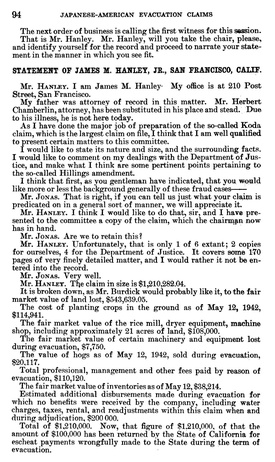

According to Hanley, on the eve of Pearl Harbor, the Koda family operated a 4,000 acre rice farm that also included a hog farm, rice inventories, and processing equipment. In total, the property value right before the incarceration amounted to $1.24 million, and even this sum did not take into account the $1.4 million in lost sales incurred by forced removal. In his words, Hanley described the farm as a “factory in the field,” borrowing the title of Carey McWilliams’s study of the same name.

Hanley testified that the Koda family’s financial losses happened not just because of forced removal itself, but also because outside members of the company’s board took advantage of the situation to defraud the family. In January 1942, a rice broker from San Francisco named John Mengola offered to purchase the Koda Farm’s rice mill – a mill valued at $100,000 - for $60,000. The Koda family refused the deal. In February 1942, with Executive Order 9066 decreed and anti-Japanese sentiment at its highest pitch, Mengola and his attorney, Marshall Leahy, approached the Koda family to lease the farm. The family agreed to the contract, and leased the farm to Mengola’s company.

In April 1942, California state Attorney General Earl Warren’s office filed an escheat case against the Koda family under California’s Alien Land Act. Coming at a time of forced removal, it was a stunning (and likely politically motivated) abuse of prosecutorial discretion. Thus, on the eve of their departure from their homes, William Koda and other Japanese American officers of the company took the step of resigning from the company’s board. John Mengola and a group of his employees then assumed management of the farm in their absence.

In the months that followed, the federal government government incarcerated the Koda family at the Merced Detention Center and later at the Amache Concentration Camp in Colorado. After entering camp, the Koda family did their best to conduct business on behalf of their fellow Japanese Americans. Keisaburo Koda served as president of the camp’s cooperative.

During their incarceration, the Koda family regularly met with employees of Mengola to discuss the farm’s management. Hanley subsequently testified that in August 1942, as a result of mismanagement by Mengola, an epidemic of hog cholera broke out. The Koda family, then in the last days before their transfer from Merced Detention Center to Amache Concentration Camp, failed to persuade the outside members of the board to change management of the company. At the same time, attorney Marshall Leahy pressured the family to donate to the campaign of his friend Robert Kenny, Democratic nominee for Attorney General, stating that his election would help end the escheat case. The family agreed, and Kenny was later elected.

Despite Kenny’s election, the threat of an escheat suit hung over the Kodas’ property.

Leahy and Mengola took advantage of the uncertainty to pressure the Koda family to transfer their property to Mengola temporarily, arguing that such a transfer would end the state’s escheat case. The Koda family finally agreed, and a company named Mill Farms took over the property. Once the property was placed under title of Mill Farms, employees of Mengola began selling parts of the farm property. Although the Koda family received word of this betrayal, camp administrators provided little assistance to the Koda family in stopping these actions. Even after the Koda family was released from camp in 1945, Mill Farms agents continued to sell parts of the original Koda property.

In late 1945, after returning to the area, the Koda family contacted an attorney, James Hanley, Sr., who filed fraud suits against Mill Farms. The Koda family was able to recover only 984 of their original 4000 acres, along with $30,000 in restitution. After resuming control of these remaining assets, the Koda family then used their funds to purchase a new mill to resume rice production. According to Hanley Jr., if it had not been for the success of the rice crop in the immediate postwar years, the family would have failed.

Following the death of James Hanley Sr., his son, James Hanley, Jr., took over their case. Hanley Jr., although not a practicing lawyer, helped to compile a claim for the family under the Evacuation Claims Act of 1948. The Koda family also hired attorney James C. Purcell – known for representing Mitsuye Endo in her case before the Supreme Court – to represent their claim.

The Koda family’s claim for losses of property and profits, which amounted to $2.4 million, represented the largest of the 26,500 claims submitted to the government under the Act. The text of the claim totaled 170 pages, and including statements from 200 witnesses.

In addition to testifying before the House Judiciary Committee on behalf of the Koda family, Hanley spoke to members of the committee about the limitations in the original 1948 Act that hindered the distribution of funds to claimants, and protested an amendment proposed by Representative Patrick Hillings that would limit repayment of all claims to 75 cents on the dollar of proposed claims. Hanley Jr.’s complaints, which were reproduced in the Rafu Shimpo, represented one of many against the Evacuation Claims Act, which failed to provide full financial restitution to families who suffered from the incarceration.

After submitting their claim, the Koda family faced pushback from the Justice Department. Justice Department lawyers claimed that the sales of the property under the farm managers constituted a legal transaction that benefited the family, despite the meager returns and the family’s inability to contest the sales while in camp.

Following a decade of legal arguments, the government at long last approved a claim of $362,500 for the Koda family on October 8, 1965. News of the claim appeared in such national newspapers as the Los Angeles Times, Rafu Shimpo, and Washington Post. A month later, on November 7th, 1965, a story in the Los Angeles Times profiled the Koda family, noting that, despite the deaths of Keisaburo and William Koda and the severe wartime reduction in their property, the farm’s operations still prospered, and the family had acquired new property in the postwar years. Commenting on the expansion of the farm, Ed Koda told the Times “you either go forward or you go backwards.”

Today, Koda farms still operates as one of the largest producers of rice in the state of California, producing Kokuho rice and Mochigome rice flower. The story of the Koda family and the reconstruction of their farm is a story of triumph over tragedy, but also a testament to the damages caused by forced removal and the failures of the Evacuation Claims Act.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen