Frank Masuto Kono

When he heard about the Pearl Harbor attack, Frank Kono (the Issei who served as the secretary-treasurer of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society in Chicago and was arrested in 1943 with three other Japanese) was working at his restaurant, the Indiana Restaurant, at 4248 South Indiana Avenue in Chicago.1 Soon thereafter, the FBI came and searched Kono’s house not once but twice, and he was called in by the FBI and the Immigration and Naturalization Service a total of seven times. But they never found anything suspicious, and things appeared to be quiet for the next two years.

However, we now know that Kono had been closely watched during that time, and that a process of “spot check search and interview” began in October 1942,2 probably because the name “Black Dragon Society,” associated with Kono's name, was secretly reported to the police by an unknown informant . In addition, eighty-five Black radical cultists, who were suspected to be followers of “Takahashi” (real name Naka Nakane), and therefore possibly associated with the Black Dragon Society, were arrested in Chicago in September 1942.3

In an interview at his home, Kono was “closely questioned concerning his membership …with Koku-Ryu-Kai, the Black Dragon Society, but he denied membership in any organization other than the Japanese Mutual Aid Society.” Kono further stated that “the Koku-Ryu-Kai is not in existence in the Midwest but they did have an organization out on the West Coast prior to the war.” Kono denied any connection with African American organizations or individuals.4

A year later, Kono was apprehended on December 2, 19435, sent to the Cook County jail in Chicago, and then to a detention center in Detroit.6 At a hearing in January 1944, he was asked whether he knew Takahashi (aka Naka Nakane) and he answered “only [by Takahashi’s] reputation” and “denied any connection with Negro groups.”7 With no criminal record and no charges pending, he was given interim parole for travel to Chicago in February,8 sent back to Chicago for another hearing, and again back to Detroit after two weeks.9 After three months of detention in Detroit and Chicago, his parole was granted on March 4, 1944,10 and it continued until November 15, 1945, when it was terminated.11

Kono was born in Hiroshima in December 1895 and moved to Kauai Island, Hawaii in December 1915 when he was twenty years old, as his parents had been running a general store in Kapaa, Kauai since 1897. While helping out at his parents’ business over the course of five years, Kono took side jobs reporting for local Japanese newspapers such as the Kauai Shimpo and a branch of the Hawaii Shimpo. Soon thereafter, he went to Honolulu and worked at the main office of the Hawaii Shimpo.12

In April 1920, Kono traveled to San Francisco to look for new challenges, but since migration of Japanese laborers from Hawaii to the US mainland had been prohibited since 1907, he used the title “San Francisco Branch Manager of Hawaii Shimpo” to hide the fact that he was looking for work. He worked in San Francisco as the secretary of the Japanese Association and for Japanese newspapers such as The New World for two years.13

In San Francisco, Kono met Toyozo Tsukada, who was from Chicago,14 and decided to move to Chicago with him in April 1922.15 Kono was very ambitious and determined about pursuing a bachelor’s degree while employed as a “schoolboy” (male issei student working his way through school as a domestic helper) for a white Catholic family in Chicago.16

In an article published in the San Francisco newspaper he had worked for, he compared “schoolboy” life in California and Chicago, and reported that “schoolboy” life was much harder in Chicago —an almost impossible lifestyle. Although tuition was much higher in the Midwest and Kono wasted a year out of school since he was unable to pay tuition, Chicago was actually a good place to study for students with money, as there were a lot of schools, most of which were bent upon getting students to enroll and granted degrees for little work, except for the University of Chicago and Northwestern University. One very interesting observation Kono made was that the Japanese in Chicago were very indifferent to teach the Nisei how to speak and read or write the Japanese language.17

Having given up on college, Kono began working in restaurants to support himself. First he worked as a cashier at the Kobe Lunch, run by Tom Ito at 634 State Street. The restaurant never closed and its customers were poor laborers, so Kono could not expect any tips from them.18 After working for several years at various restaurants as a waiter and cook and saving enough money to buy the premises, in 1925, Kono opened a billiard parlor in a barber shop, the “American Pool Room and Barber Shop,” at 818 North Clark Street.

At first Kono ran both the bililard and the barber shop by himself, but in October 1926, Rales, a Filipino, joined the management of the barber shop.19 While the owners of the barber shop were Japanese and Filipino, the actual barber was Filipino. Two-thirds of the customers were Filipino and one-third Japanese.20 The billiard parlor was so popular among the Japanese that it hosted a tournament in 1927, when Kinrei Matsuyama, an internationally-known, Japanese professional billiard champion, was in Chicago.21

Kono became more involved in the restaurant business from this point on. After gaining experience as manager of Tokyo Restaurant No. 3 on North Clark, which Charles Yamazaki owned,22 in 1926 Kono bought the Fuji restaurant on the corner of Clark and Division from Frank Sumida. Kono kept the Fuji open 24 hours a day, and worked from 8 AM to 8 PM.23 Kono also bought out Yamazaki’s restaurants, such as the one at 230 West Chicago Avenue24 in 1927, and the Indiana Restaurant in 1937. In 1931, Kono opened another restaurant at 5852 Wentworth Avenue and ran it until April 1933. Then he switched to a restaurant at 2422 West Madison Street.25 One of Kono’s restaurants, the Madison Restaurant, was reported to the Japanese government as having opened with capital of $2,000, claimed annual sales of $30,000, and had twelve employees.26

After the Japanese Mutual Aid Society was established in January 1935, Kono was actively involved as its treasurer from the very beginning. When the Japanese Young Men’s Christian Institute, (JYMCI, 747 E. 36th Street) started by Reverend Misaki Shimadzu in 1908, finally dissolved at the end of 1937, the Japanese Language School and Japanese Christian Church of the JYMCI moved to 214 West Oak Street in January 1938.27 Later, the school was put under the management of the Mutual Aid Society due to the financial difficulties it had endured since January 1939.28 Kono became a teacher, and later, a head teacher at the school.

Classes were usually held once a week on Saturdays, but were held twice a week during the summer months.29 The school had twenty Nisei students. Isamu Sato, a University of Chicago student who was to graduate in 1941,30 taught alongside Kono.31 The school had two classrooms, one on the North Side and one on the South Side, as Japanese were spread out all over the city, and it was very difficult to get all the students together in one class.32

The premises at 214 West Oak had become a social center for Japanese residents, as it housed the Chicago Japanese Club, a new group formed in May 1939,33 as well as the Japanese language school, the Japanese Christian Church, the Nisei Club, and the Mutual Aid Society. Kono maintained a residence on the premises.34

Since he was living at the center of Chicago's Japanese community, was engaged in Japanese language education and the “pro-Japan” activities of the Mutual Aid Society (such as contributing to the war effort in Japan through the Japanese Consulate in Chicago,) Kono was prepared to be arrested as a leader among the local Japanese residents.35 He was not, however, prepared to be arrested for suspicious connections with the Black Dragon Society, but there were a few signs that malicious minds were suspicious of Kono.

One such sign was the location and staff of the Indiana Restaurant, which he had operated since December 1937. It was located “in the section of the city which is wholly populated by negros and … all of his patrons with very few exceptions are of the negro race” and “he employed three colored girls, two Japanese Issei, and one colored male dishwasher at his restaurant.”36

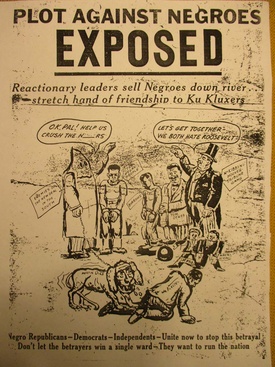

Other evidence was secured “as a result of a search made incidental to the apprehension of Frank Masuto Kono” at his place of business, 4248 South Indiana Avenue.37 This included “a memorandum pad, with no name to designate the owner” which had entries listing several meetings with the members of the Onward Movement of America,38 and the other was a “pro-negro propaganda pamphlet” containing the words “Plot Against Negroes EXPOSED-Reactionary leaders sell Negroes down river… stretch hand of friendship to Ku Kluxers.”39 Maybe Kono received this memorandum pad in 1939, when African Americans under the influence of Naka Nakane came to Chicago from Detroit and visited the Mutual Aid Society to meet Charles Yamazaki, president of the society, for the purposes of donating some money to Japanese soldiers in China.40

In September 1942, Kono married a Nisei woman, Mitsuye Maruyama, who was born in Billings, Montana, in 1908.41 During the interrogations in Detroit, it was Mitsuye who served as Kono's interpreter.42 According to an FBI report, Mitsuye made a very favorable impression with the authorities. She stated that she “would never have jeopardized her name or reputation or the reputation of her family by marrying an individual such as [Kono] at a time of war if she had the slightest notion that he was engaged in any subversive activities.”43

Kono’s name was included by the Japanese government on the manifest of the Gripsholm, a Swedish cruise ship that was used to transport civilians and prisoners of war between the U.S., Germany, Italy, and Japan. Kono was permitted to board the second exchange ship, which left New York in September 1943,44 but he did not go back to Japan and instead stayed in Chicago, where he became a U.S. citizen on December 13, 1955.45 After sixty-three years in Chicago, on November 24th 1985, he was finally allowed to go to his rest in the Japanese section of Montrose Cemetery, which he worked hard to obtain with fellow Issei activist and president of the Mutual Aid Society, Charles Yamazaki.

Notes:

1. Ito, Kazuo, Shikago ni Moyu, page 214.

2. FBI report 11/4/43, 146-13-2-23-1164, RG60, General Records of the Department of Justice, WWII Alien Enemy Interment Case Files 1941-1951 Box 272, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

3. Day, Takako "Suspicious Points of Contact in Pre-War Chicago—Eizo Yanagi - Part 1" (Discover Nikkei, March 27, 2019).

4. FBI report 11/4/43.

5. FBI report 3/7/44.

6. Ito, Kazuo, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-Shi, page 321.

7. FBI report 3/7/44.

8. Ibid.

9. Ito, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-Shi, page 321.

10. FBI report 3/7/44.

11. Ibid.

12. Ito, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-Shi, page 177.

13. Ito, Shikago ni Moyu, page 117.

14. Shimadzu, Misaki, List of Visitors to the US Chicago Japanese YMCA, page 211.

15. Ibid, page 77.

16. Ito, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-Shi, page 177.

17. Shin Sekai, October 2, 1924.

18. Ito, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-Shi, page 223.

19. New York Shimpo October 23, 1926.

20. Ito, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-Shi, page 227.

21. Nichibei Jiho, April 23, 1927.

22. FBI report 11/4/1943 .

23. Ito, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-Shi, page 223.

24. Chicago City Directory 1928-29.

25. FBI report 11/4/1943.

26. Kaigai Nihon Jitugyo-sha no Chosa, Vol 6.

27. Stotz, H.A, Relations of the Japanese Young Men’s Christian Institute to the Young Men’s Christian Association of Chicago, Chicago YMCA Collection, Chicago History Museum.

28. Nichibei Jiho, November 19, 1938.

29. Nichibei Jiho, July 8, 1939.

30. University of Chicago Magazine, February 1994.

31. Nichibei Jiho, November 4, 1939.

32. Nichibei Jiho, March 18, 1939.

33. Nichibei Jiho, May 27, 1939.

34. FBI report 11/3/1943.

35. Ito, Shikago ni Moyu, page 220.

36. FBI report 11/3/1943.

37. FBI report 1/19/1944.

38. Ibid.

39. Enclosure with FBI report 4/11/1944.

40. Day, Takako "Suspicious Points of Contact in Pre-War Chicago The Japanese Mutual Aid Society and Charles Yasuma Yamazaki - Part 2," (Discover Nikkei, June 19, 2019).

41. Petition for Naturalization, Chicago, September 23, 1955.

42. Ito, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-Shi, page 322.

43. FBI report 3/7/44.

44. Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Nichibei Kokan-sen Kankei, A-7-0-0-9-24-1.

45. Oath of Allegiance, December 13, 1955.

© 2021 Takako Day