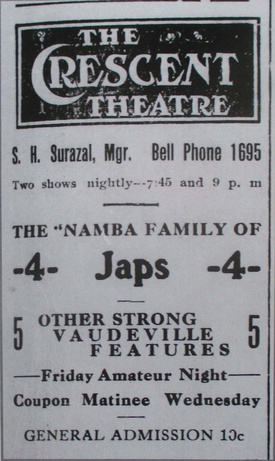

By the time the U.S. entered World War I, Namba had moved from 1227 E. 71st to 6348 Dante Avenue in Chicago. Known as the “Namba House,” this address was the haunting of many Japanese performers.1 The other residents were performers such as actor Toyokichi Totsuka, age twenty-four; Katsumi Sato, age twenty-three; Daigoro Fujisawa, age twenty-three; and Asashige Takagi, age twenty-three, who was a jiu-jitsu performer for the Ringling Bros Circus.2 A few years later, Katsumi Sato became an independent performer and ToyokichiTotsuka joined Sato’s troupe at 6544 Blackstone Avenue.3

Kumataro’s “son,” Kaichi Namba worked with his “father” as a performer,4 but his other “son,” Kiyo, was employed by K. Yamamoto at Revere House at 417 North Clark Street.5 The K. Yamamoto listed in the census was probably Kurushige Yamamoto. Kurushige and his wife, Laura, both from Japan, and who were twenty-four and twenty years old, were actors. They lived in Chicago for a while as part of a touring troupe that had more than eighty performers, including two Chinese and a performer by the name of Daigoro Fujisawa.6

Fujisawa was born in 1894 in Tokyo and had arrived in New York in 1908, when he was fourteen years old. He had previously lived with the Namba family at 6348 Dante Avenue in Chicago and was employed by the Kimiawa Troupe in Chicago.7 In the 1920 census, he was listed as being married to a Texas-born white woman by the name of Bertha.8

In 1916, actor Kaichi Arayama, who had been brought to the U.S. by “Mrs. Namba” in 1905, died and was buried at the Oak Woods cemetery in Southside Chicago. He was only sixteen years old, and Namba and Iku were recorded as his parents.9

The Namba troupe was well-known in the Japanese and Japanese American community in Chicago. When the Japanese Association of Chicago celebrated the Emperor’s birthday at the Drake Hotel on November, 3 1916, the Namba troupe performed,10 and was so well-received that they were invited to repeat their act in 1917.11 The Namba troupe also represented the Japanese community in a big Chicago Independence Day Celebration Parade.12

Although the numbers of both audiences, and members and employees of the acrobatic troupes declined due to the draft, Japanese performers were still active throughout World War I. For example, Jirosuke Tamaki and Hero Matsuoka were employed by the Ringling Brothers Circus and other troupes around 1918.13

After the war ended, the All-American Exposition was held at the Coliseum in Chicago from August 30 to September 14, 1919. September 9 was “Japan Day” at the Exposition, and local Japanese performers demonstrated talents such as singing, piano playing, koto and kendo demonstrations, and dancing. One performer, George Harada, executed an acrobatic bicycle act at the Exposition.14 Harada had settled down at 1710 Clybourn Avenue in Chicago as an actor in the early 1910s,15 and managed to survive by shifting from a performer to operating a Japanese goods store in or around 1926.

When World War I ended in 1918, Kumataro Namba was about forty-seven years old. He must have been waiting for the right time to change his career from performer to show proprietor. By 1917, it seems that he had succeeded in establishing himself as a respected businessman in Chicago.

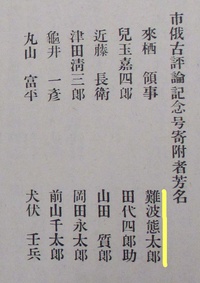

When the Chicago Japanese Business Association was founded in 1916, Namba was one of its twenty-eight original members.16 And in 1916, when the Japanese club at the University of Chicago published their bilingual magazine, Shikago Hyoron / Japanese Student Review, Namba was listed as one of twelve donors, which included Japanese Consul Saburo Kurusu.17

Furthermore, judging from the parties he was invited to, Namba was part of a respectable social circle; when a group of Japanese Diet members visited Chicago in November 15, 1917, they were invited to welcoming parties hosted by Consul Kurusu at the University Club and by the local Japanese community at the Morrison Hotel. Those who attended the parties with Japanese Consulate staff included prominent and successful businessmen such as Tomihei Maruyama, Sentaro Maeyama, Chisaburo Takito, and Charles Yamazaki, as well as community activists such as Christian minister Misaki Shimadzu and Shigeji Tani.18 Kumataro Namba also attended these parties.19

Did Kumataro Namba disband his troupe because he thought he had reached an important milestone in his life? Or did one of his “sons” take over the Namba troupe?

By the time he went back to Japan with his wife and son, George Tsune, in 1919,20 he had fully retired as a performer and assumed the role of a merchant and provider of rare exhibits. On this trip to Japan, Namba was in charge of bringing back twenty-one boxes of rare and ferocious animals from Texas, including large snakes, raccoon dogs, and wildcats that were used for sideshow attractions at various temple festivals in Japan.21

However, he kept the Chicago address where his sons still lived, and eventually returned to the city as a show proprietor. At the Tokyo Peace Memorial Exhibition in Ueno Park from March to July 1922, Namba Kumataro was hired as a talent scout by Yumindo Kushibiki, the so-called “Exhibition King,” who was commissioned to provide the entertainment.

In February 1922, Kushibiki sent Namba to the U.S. to look for American entertainers, and just two weeks later, Namba brought back fifteen American performers, including three dancers, two acrobats, four musicians, a cowboy and cowgirl, a Christian shepherd, and a three-member chorus.22 They probably performed at an entertainment hall located in the section called “International Street” at the Fair.23

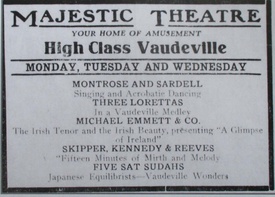

While it is unknown how long Namba actually kept his residence in Chicago, the Namba Japs—two highly accomplished performers, one of whom was Kiyo Namba—were still on the road performing at the County Fair in Oklahoma in May 192824 and at the Fall Festival in Missouri in October 1928.25 We do know that Kumataro Namba was in Chicago in 1929. That was the year that Otoichi Kinoshita came to Chicago as a member of a delegation to investigate the “industrial rationalization” movement in America and met Kumataro and Iku Namba in the Japanese Lunch Room at the Stevens Hotel.

In his account, Kinoshita described Namba’s voice in conversation as that of a sea captain scolding other fishermen working on the rough waves of the Japan Sea.26 The Lunch Room was decorated with a mural that depicted scenes reminiscent of the Tokaido Gojyu-san tsugi (53 Stations of the Tokaido). Kinoshita purportedly observed several white women observing Iku, and comparing her to the Japanese women painted in the mural.

Notes:

1. Ito, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-shi, page 251.

2. World War I Registration.

3. 1920 Census.

4. World War I Registration.

5. Ibid.

6. 1920 census.

7. World War I Registration.

8. 1920 census.

9. Illinois death index.

10. Nichibei Shuho, November 16, 1916.

11. Nichibei Shuho, November 17, 1917.

12. Nichibei Shuho, July 13, 1918.

13. World War I Registration.

14. Nichibei Jiho, September 3, 1919.

15. 1914 Chicago City Directory.

16. Cororado Shimbun, August 3, 1916.

17. The Student Review, May 1916.

18. Day, Takako, Japanese Christians in Chicago “Chapter 2: Misaki Shimazu — Birth of the Japanese Christian Community in Chicago,” (Discover Nikkei, July 25, 2021).

19. Yamada, Kiichi, “Zaibei Nikki”, Senji oyobi Sengo no Beikoku.

20. Nichibei Shuho, May 24, 1919.

21. Nichibei Shimbun, June 9, 1919.

22. Shin-Sekai, February 9, 1922, Nichibei Shimbun, February 17, 1922.

23. Heiwa Kinen Tokyo Hakuran Kai Shashin-cho, National Diet Digital Collection.

24. The Perry Journal, May 26, 1928.

25. Daily Democrat-Forum and Maryville Tribune, October 2, 1928.

26. Kinoshita, Otochi, Amerika no Sangyo Gori-ka Undo wo Miru.

© 2022 Takako Day