One exceptional Nisei, the different pieces of whose life I have been trying to investigate, was a man by the name of Yoshitaka Wilfred Horiuchi. In the course of a 50-year career, operating in different places and under different names, he made contributions in a variety of fields, from the silver screen to government to education to business.

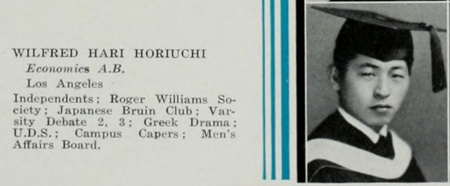

Yoshitaka Wilfred Horiuchi was born in Lihae, Hawaii, in 1909, the youngest son of six children of Tohei Horiuchi, a sugar plantation worker, and his wife Suye. He grew up on Kauai and attended Kauai High School. After graduation, he migrated to Los Angeles, where he joined his brother Kenji Horiuchi, eight years his senior, and Kenji’s wife Jane. The young Wilfred Horiuchi, as he was then known, enrolled at UCLA in 1928 as an Economics major.

As a UCLA freshman, Horiuchi started debating. In spring 1929, he and a classmate, Peter Takahashi, competed in debates organized by the local Japanese community. Later he and Goro Murata organized debate competitions among high school students at the Japanese YMCA in Little Tokyo. Horiuchi soon joined the varsity debating squad.

In March 1933, under the name Wilfred Hari, he participated in a radio debate on station KMTR entitled, “War Clouds Over Asia.” He defended the Japanese position on the Manchurian question, while another student, George Kwon, supported the Chinese position. Horiuchi remained active in student affairs as a member of the University Affairs Board and International Service chairman of the Roger Williams Society.

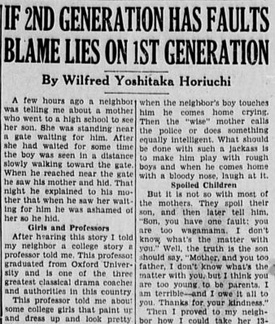

Meanwhile, Horiuchi dabbled in journalism. In 1930 he joined the newspaper Rafu Shimpo, and over the following years he wrote a regular column titled “Youth Speaks” (signing it variously as Wilfred Horiuchi, Wilfred Y. Horiuchi, Wilfred Yoshitaka Horiuchi, and Wilfred Hari). He also wrote for Shin Sekai. His columns often took a light-hearted, comic tone. In one 1933 column on mercenary brides, he cracked, “Talking about marriage reminds me of auctions. The highest bidder gets the emerald.” Yet he was capable of serious discussion. In fall 1931 he wrote in defense of “petting” (i.e. non-penetrative sex), citing white educators on the subject.

In October 1932 he published a provocative weeklong series in Shin Sekai on a question of great delicacy for Nisei. Horiuchi’s title succinctly expressed his skeptical views: “Does college education pay? (Don’t be too sure!)” With heavy irony, he advised, “Yes, you better send your son to college and then after he graduates he can become a policeman, a streetcar conductor, or a garbage collector. Look at me—l go to college and I'll work in the fruitstand after I graduate. That’s college education.” The series drew considerable attention (and some impassioned criticism) from readers. In 1933 he published a satirical playlet, “Mr. and Mrs. Cat,” which took the position that it was better for Japan to stay in Manchuria if the alternative was a takeover by the Soviet Union.

In his last year at UCLA, Horiuchi became involved in theater and was “bitten by the acting bug.” He began studying drama under Evalyn Thomas, director of classical Greek Drama. His first recorded performance came in Spring 1932, in a UCLA production of Aeschylus’s Agamemnon. In October 1932, he joined the Beverly Hills Community Players, in the cast of a play called Insult, acting under the stage name Wilfred Hari.

According to a summary in Variety, the play’s main character is a princess, the daughter of a former British Ambassador to Japan, “Who has been imbued with oriental philosophy by her Japanese servant Oto-San.” The Daily Bruin praised Hari’s performance, “In the important role of the too-faithful Japanese houseman.” Variety countered,“Wilfred Hari, Japanese boy, was the servant, but lacks experience in a difficult part.” Whatever the critics’ strictures, Hari was cast soon after as Baron Yoshida in the play The Lausanne Conference, produced by the UCLA dramatic department. He was also featured in a student comic revue, Kampus Kaleidoscope.

In early 1933, he appeared in Henry Gordon’s play Undress Parade, a drama set in a Long Island roadhouse. The Los Angeles Daily News was scathing about the play: “A dirty turk located in a house of ill fame.” Soon after, he opened in two other plays, The Spider and The Middle Watch. He gained commercial theater experience in September, in a production of Gilda Veresi Archibald’s play, Enter Madam, at the Pasadena Playhouse. (Foreshadowing later roles, Hari portrayed a Japanese houseboy.) According to one source, he wrote two Japanese plays which were performed by a local Japanese organization. He also worked as a concert singer.

1934 was a banner theatrical year for Hari. That spring, he performed in a drama, Quicksand, at the Spotlight Theater. Hari played two parts. His character, “Togo,” for which he wrote his own lines, was a comic role described in Rafu Shimpo as a combination of Frank Watanabe (the caricatured “Japanese student” radio character of the era), Harold Lloyd, and Charlie Chaplin. He also portrayed “Angelo,” under the stage name “George Splevin.” Hari also appeared in Miner's Gold, by Agnes E. Peterson, and in Katherine Kavanaugh’s So This is Love, as a comic Japanese butler. He returned to UCLA for a production of Aeschylus’s Eumenides. In early 1935 he performed in another play, Soaring, at the Spotlight Theater.

Even as he pursued his theatrical career, he broke into Hollywood films, playing a variety of uncredited roles as “oriental” domestics speaking fractured English. His first movie, Melody in Spring (1934), was a musical about a radio singer (Lanny Ross) romancing a young lady (Ann Sothern). Hari had a walk-on as “Suzuki.” Soon after, he played Sato, the cook of Paul Lukas’s leading character, in Affairs of a Gentleman. When Enter Madam, the play in which he had previously appeared, was adapted for the screen, Hari was selected for the cast. He played Tamamoto, the Japanese chef of leading man Cary Grant.

Hari also had bit parts as domestics in a variety of pictures: Spring Tonic (1935) with Lew Ayres; The Cowboy Star (1936) with Charles Starrett; and Venus Makes Trouble (1937) with James Dunn and Patricia Ellis. In the 1936 movie Theodora Goes Wild (1936) starring Irene Dunne, he played Melvyn Douglas’ valet. This time, at least, his character spoke unaccented English and was given a comic bit, deploying a battery of alarm clocks to rouse his sleeping employer.

In October 1935, Hari was engaged as a writer and performer for a radio show, “Rain and Shine,” broadcast over station KHJ by the Don Lee radio network (a CBS affiliate). The program, which starred Captain Bill Royle as anchorman, was broadcast six days per week from 6 to 8. Hari not only played a comic role, but also presented recordings of Japanese music and sang Japanese songs. Los Angeles Times reviewer Carroll Nye praised the show, and especially the work of “Wilfred Hari, American-born Japanese with a flair for comedy.”

Hari was successful enough that shortly afterwards he signed another contract with the network to appear three times per a week in the “Happy-Go-Lucky Hour” (2 to 3 p.m.) over KHJ. Working under the name Togo Hari, he conducted the “Fountain of Knowledge,” giving advice on questions such as marriage, investments, and choosing careers. In 1937 Hari appeared as a comic Japanese houseboy in the radio series “House Party,” on KHJ. His voice was also heard on the Silver Theater radio series on CBS during fall 1937, in “First Love,” starring Rosalind Russell and James Stewart.

It should be mentioned that, beyond his skills as a performer, Hari had a knack for public relations and self-promotion. He audaciously advertised his acting services, including his photo and telephone number, in the trade newspaper Hollywood Pictograph. He was then featured in Pictograph articles puffing his accomplishments in films (with texts that sound suspiciously like he wrote them himself). For example, one stated:

“Hari is inimitable and versatile in his interpretations as an Oriental actor, and shows real class and ability with his capable work. He is also a baritone singer, and renders both popular and classic numbers worthy of special mention. Mr. Hari is up for another important role at one of the major studios. His good work speaks for itself.” (March 31, 1934).

In September 1937, Wilfred Horiuchi married Martha Haruko Sato. Over the next two years, Wilfred Hari largely disappeared from performing (One source lists him in the cast of the landmark 1939 movie “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” but this is unconfirmed). Like other Japanese American actors, he may have been victimized by blacklisting born of popular anti-Japanese hostility following Tokyo’s invasion of China, or he may have simply tired of the kinds of roles available to him. Whatever the case, he continued to write plays and radio scripts, and decided to return to his studies.

In fall 1938, Horiuchi announced that he would enroll at USC law school. While this seems not to have occurred, he entered the Graduate School of Economics at USC in 1939, majoring in economics and with an international relations minor. In July 1941, he was awarded an MBA degree by USC. His thesis was titled, “Japanese-American trade in raw cotton and raw silk with emphasis upon methods of financing.” He then undertook doctoral studies in international relations, with the declared thesis topic, “An Analysis of Interventionist and Isolationist Propaganda in the United States, 1939-41.” He later claimed that he had received a Ph.D. in International Relations, but this seems unlikely.

It was during his graduate school days that Wilfred Hari was recruited to appear in the Warner Brothers movie Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet, staring Edward G. Robinson (with the legendary cinematographer James Wong Howe behind the camera). The film told the story of the great scientist Paul Ehrlich, who discovered “Formula 606” (AKA salvarsan), a cure for syphilis. Hari portrayed the real-life Japanese researcher Dr. Sahachiro Hata. It was his most substantial screen role and the first in which he did not play a domestic.

Hari appears in several scenes. However, his only real dialogue comes in a single one, in which Dr. Hata greets a committee visiting Ehrlich’s laboratory. Its members. shocked to see an Asian doctor, ask Hata whether he is German, to which he replies in unaccented English that he is not. When the visitors inquire what his work is, Hata explains that it involves injecting laboratory animals—unlike his colleagues, he injects them with chemicals and not infectious disease germs. When asked what Dr. Ehrlich himself does, Hata replies with a smile, “he thinks.” The film rather underplays Hata’s contributions, portraying him simply as one member of a larger scientific team of Ehrlich’s assistants—in reality Hata was Ehrlich’s full partner and collaborator in developing salvarsan.

Yet his presence in the movie has a larger significance. The visitors complain to Ehrlich about his employing an “oriental” instead of a scientist of “pure German blood” and insist that he be discharged. Ehrlich refuses and asks the committee to leave. Although direct allusions to Ehrlich’s own Jewishness were apparently excised from the film, the scene serves to rebuke Nazi-era German racism. Writing in Nichi Bei, Larry Tajiri praised the scene for that reason:

“One of Dr. Ehrlich's principal assistants in his war on disease is the Japanese doctor, Hata, who is played by Wilfred Horiuchi trade-name Wilfred Hari, the only Nisei actor who is doing anything in Hollywood these days. Dr. Ehrlich’s employment of Hata. a non-Aryan, creates a minor stir among German bureaucrats of that day…Hollywood proves…that men of many races, European, Chinese, and Japanese, can work together, proves by this great film of the life of a Jewish scientist who was above all things, a great human being.”

Horiuchi’s draft card from fall 1940 lists him as a Warner Brothers employee, but he made no further films before December 1941.

To be continued ...

© 2022 Greg Robinson