In recent years, I have done a good deal of research on James Edmiston. Through my reading, I discovered that James Edmiston was director of the WRA resettlement office in San José at the close of World War II, as Japanese Americans returned to the coast, and that his support for them led to attacks on him as well. I also read James Edmiston’s 1955 novel Home Again, a “documentary novel” about a Japanese American clan through immigration, settlement, and wartime confinement, and their return to the West Coast.

Like many readers and commentators, I long assumed that the WRA official and the author were the same person. In fact, they were two different individuals—a father and son—who each led extraordinary lives.

The elder Edmiston was born James Ewen Edmiston on August 13, 1887, in Dayton, Washington (then a U.S. territory). He was the second child of Francis L. Edmiston, a carpenter from Arkansas, and his wife Mary. By 1900, the family was living in nearby Lewiston, Idaho. The young James Edmiston (known as “Jim” or “J.E.”) attended Lewiston High School, where he ran track and performed in the senior class play. He apparently attended two years of college.

Throughout his younger years, Edmiston seems to have been ever-restless. By 1910 he was living in Yakima, Washington, where he worked as a newspaper reporter, and also managed a local baseball team. Soon after, he moved to Wallace, Idaho, where he worked for the Wallace Times newspaper.

Soon after, he was elected president of the Coeur d'Alene League, an unofficial baseball league, and subsequently resigned his office to manage the Wallace club. On March 25, 1911, he married Florence E. Edmiston (the couple stated, no doubt tongue in check, that if they had not had the same uncommon family name, they would never have met and married).

Within a year of their marriage, Edmiston and his wife moved to the San Francisco Bay area. At first, they purchased a ranch near Sebastopol and farmed. James E. Edmiston joined the Petaluma Daily Morning Courier’s staff, then became a correspondent for the San Francisco Chronicle. In the next three years, the Edmistons had three children. Soon after, they settled in San Anselmo, CA. (In June 1915 “The Hearthstone City”, an original poem by J. E. Edmiston dedicated to San Anselmo, was read at a meeting of the local Hearthstone Club).

In addition to his newspaper work, in 1916 he became Secretary of the Central Marin Chamber of Commerce. As secretary, he took an active role in civic affairs and public welfare projects. In April 1917, after the United States entered World War I, he took a leave from the Chamber of Congress, and returned to newspaper work. He also offered his services to the federal government, and headed a local publicity committee for the Liberty Loan bond drive.

In 1919, following the end of World War I, J. E. Edmiston purchased the “Silverwood” orchard, a large piece of property in Jackson County, Oregon. In addition to his agricultural production on the ranch, he found a seam of coal underground on his property, which he expressed his intention to exploit. Soon after, he took a job as commercial secretary of the Oregon growers cooperative and subsequently became president of the Jackson County Farm Bureau.

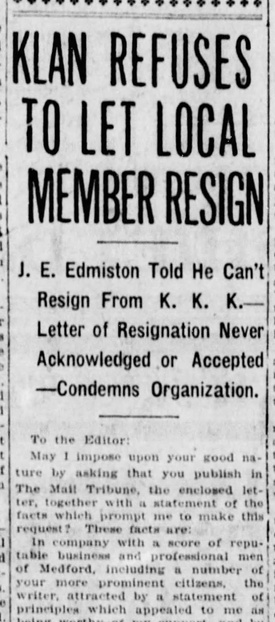

In early 1922, shortly after settling in Medford, Oregon, Edmiston joined the Ku Klux Klan. He later explained that he had been one of a number of local business and professional men who had been recruited by the Invisible Empire, whose leaders presented a statement of principles he considered worthy of support: For the privilege of joining the Invisible Empire, he stated facetiously, “I separated myself from ten (count ‘em) perfectly good American dollars [and] attached my name to a card.” He then went through a very brief initiation, in which he was informed that the Order was built on three doctrines for which its members would lay down their klanly lives:

1. Maintenance of white supremacy

2. Separation of Church and state

3. Law and order enforcement

While by his own account Edmiston was initially inactive in the Medford Klan branch, he was aroused to action in early 1922 when Klansmen kidnapped a local African American whom they accused of attacking white women. A trio of nightriders took the man out to a forest, strung him up as if to lynch him in order to make him “confess” (which he refused to do), then ran him out of town.

In response, Edmiston published an open letter in the Medford Mail-Tribune in which he denounced the Klan as a lawless institution and announced his resignation. He recounted the circumstances of his joining the Klan and asserted that he had originally not believed it responsible for the nightriders’ outrages, but that when he had asked its members to disavow them and aid in punishing them, they had failed to do so.

Following his resignation (which Edmiston claimed was not accepted), he was the recipient of threatening letters. In summer 1922 he testified before a grand jury about the lynching and the following year, he was a witness for the prosecution at the trials of three nightriders (who were acquitted by an all-white jury).

Despite his involvement in controversies over the Klan, Edmiston’s businesses prospered. In 1928 he bought a large tract of land, the Meridien Orchard, for which he and a partner, W.F. Biddle, paid the hefty sum of $85,000. He grew pears in the orchard. By 1930 he had taken the position of Fruit shipping manager for the C&E Fruit company, which distributed apples for his own and other orchards. (That year, Edmiston and his wife became embroiled in the case of Edmiston v. Kiersted, a lawsuit over a sale of property they owned, which was ultimately decided in their favor by the Oregon Supreme Court).

Not much about J. E. Edmiston appears in the public record during the 1930s. It is plausible to suppose from this that his business affairs did not prosper during the Great Depression. In April 1933, after the Roosevelt administration came to power and legalized the sale of 3.2 % beer (before sponsoring a Constitutional amendment to do away with Prohibition entirely), Edmiston formed a new company, Oregon Breweries and Hopyards, Affiliated, and announced to the Portland Chamber of commerce his intention to open a factory that would produce beer from locally-grown hops. It is not clear whether the project was ever realized.

Sometime between 1935 and 1940, he and his wife moved back to San Francisco, where he found work as manager of a bedding company. He subsequently moved to Sunnyvale, CA and worked as a salesman.

In March 1945, after the Takeda family returned from the Gila River camp to the San Jose area, they were attacked by terrorists, who doused their house with gasoline, set it on fire, then shot at the Takedas as they fled outside. In response, the WRA established a new office in San Jose and hired Edmiston to run it. Edmiston was charged with relocating returnees to the Santa Clara and San Joaquin counties.

Once installed in his new job, Edmiston formed a Relocation Council to advise on the work of resettlement, and helped organize a San Jose branch of the California Council for Civic Unity to secure outside assistance. He was initially optimistic, and publicly praised the general attitude in the Santa Clara valley toward the return of Japanese Americans, citing the cooperation he received. He concentrated on aiding students with resettlement and re-enrollment in college.

According to Stephanie Hinnershitz, he reported to the Council in April 1945 that Stanford University, San Jose State College, and the high schools of Santa Clara County were “warm and enthusiastic” in accepting Nisei students, despite still lingering feelings of anti-Japanese sentiment in the larger communities. By June, Edmiston had arranged for the return of some 711 persons of Japanese ancestry to Santa Clara county, whom he helped find housing and employment. He also defended their rights. When the San Jose Mercury Herald ran a story on a Nisei and used “Jap” in their headline, Edmiston published a letter to the editor protesting the use of the slur.

As more Japanese Americans returned to the area, racist opposition to their presence flared. Edmiston was active in investigating and reporting on acts of terrorism against returnees. He was targeted by ostracism and death threats.

The harassment climaxed in June, when unidentified persons came to his home and fired a shot through the breakfast room window. Although Edmiston was working outside in the garden at the time of the shooting, he heard shots fired, while his wife, daughter and two grandchildren were in the house at the time. He discovered the bullet and a shattered glass window in the breakfast room the next morning.

Santa Clara County Sheriff William J. Emig described the shooting as “accidental.” (Author Aaron I. Cavin noted that Emig subsequently refused to investigate incidents of violence against returnees, including the burning down of a house belonging to the Saito family, claiming all such acts as “accidental.”) Edmiston pointed to ballistics evidence that indicated the shots were intentionally fired from the street, at close range. The Sheriff pooh-poohed such evidence, stating that ballistics were “useless.”

H.B. Cozzens, assistant director of WRA in San Francisco, immediately requested a thorough investigation by the FBI, contending that “here was a deliberate attempt to intimidate a government agent during the performance of his duty.” Cozzens agreed that the shot could not have been accidental: its upward trajectory into the breakfast room proved that it was shot from nearby.

Edmiston continued his efforts even after the war officially ended. In September, he led the WRA to open a hostel for returnees at the Gilroy Hot Springs resort, in partnership with owner Frank Sakata and the Presbyterian Home Missions Board.

James Edmiston ran the San Jose office until the WRA closed in May 1946. He was dubbed “Suzuki” for his defense of Issei and Nisei. Edmiston asserted that his office had resettled a higher percentage of Nisei than any other district office in the United States. He told the Palo Alto Times that special recognition was due to, “the assistance of those stalwart Christians who recognize that human beings can be wrapped in pigmented skins.” In recognition of the work and progress made by the San Jose WRA office, some 40 returnees honored the staff with an Italian dinner, with James Maruyama serving as Master of Ceremonies.

According to one source, after the WRA closed its office, the U.S. State Department asked Edmiston, because of his positive experience with Japanese Americans, to come to Japan and serve in the US occupation. Edmiston seems to have declined, but his work clearly did not go unappreciated. In 1947, he helped organize a new social action group, The California Committee for Justice, “to help make Democracy work among minorities in the State.”

In 1955, upon the publication of his son’s book Home Again, James Edmiston was selected by the Palo Alto Fair Play Council, founded in 1945 to assist Japanese Americans, to be the guest speaker at their tenth anniversary meeting. In 1960, the government of Japan awarded Edmiston a citation for his humanitarian work with the WRA. He was invited to Japan to receive the award, but declined on account of old age.

In 1948, James Edmiston moved to Palo Alto. While in the 1950 census, he is listed as a “government worker,” he spent his later years working as an income tax preparer. Ms. Edmiston died in 1967, and James Edmiston moved thereafter to Monmouth, Oregon, where he died on September 27, 1973, at the age of 87.

J.E. Edmiston’s journey from Klansman to defender of democracy was unique. Twice his life was changed by racist outrages which he publicly opposed, and which led to attacks and death threats against him.

© 2022 Greg Robinson