TW: Did your family help you in doing research about your grandfather? If so, what was it like to hear your family’s stories about your grandfather and was there anything interesting you learned from your family?

KY: My father especially is a treasure chest of stories of my grandfather, but so is my uncle Taro and so was my aunt Carol. Everyone had their own relationship with our grandfather, so all of their stories are different which was among my greatest challenges in making the book. How do you honor the essence of someone who had varied and complex impacts on different people’s lives? Sometimes my conversations with family left me with more questions than answers!

That said, there are so many family stories from every era of his life. From his childhood, my father recalls stories from the vibrant Japantown of Seattle that was his home community. There were many of stories of racism he experienced as a young architect in New York City (NYC), and then again in the metro Detroit area.

There were stories of his friendships with Walter Reuther and Eero Saarinen. There is a story of him taking his family to visit a dear friend at the Tuskegee Institute and getting into a loud, public argument with a racist bus driver en-route to the institute. There are stories of him studying watercolor painting at New York University and the toll and emotional weight of designing the World Trade Center (WTC). There are anxious letters written back and forth from NYC to his parents in Seattle in the weeks prior to Pearl Harbor.

My dad and grandpa worked together for many years at my grandfather’s office towards the end of his life so my father had the unique perspective of him as a dad, an artist, and a boss. One thing I hadn’t considered was how his work changed after designing the WTC and why. It is a complicated puzzle, but my grandfather took his job as a boss very seriously. He strove to create a healthy and inspired workplace environment prior to the WTC. The office was the size that could more easily accommodate the aspirational, humanist, artistic work that he endeavored to do.

When he won the commission to design the WTC, all of a sudden, the office grew exponentially to handle the pressures and responsibilities of the project and he became boss to many more people. And then when the job was done, it wasn’t as if he would just fire all of those architects. But the expense of operating that type of office meant bigger, more corporate developers, projects, etc. and that all comes at a cost creatively, personally, and in many other ways.

I hadn’t thought much about it from the human side, but I can imagine that the shift to those types of projects, based on stories I’ve heard, it was hard on him artistically and emotionally. It’s almost like you become too successful to do the type of work you set out to do in the first place. I’ve seen it play out in many visual artists, but hadn’t really considered it from his perspective until doing this project.

TW: When researching and writing this book, did you learn about your grandfather’s architectural process? What did you enjoy learning about his process? Also, what does it feel like to know that your grandfather had created some iconic pieces of architecture?

KY: Prior to doing this book, I hadn’t connected my grandfather’s early life with the work he created. How he was made to feel, as a young Asian-American man, in the spaces he inhabited. It is my belief that those early experiences impacted him profoundly and made him want to create spaces that lead to the opposite emotional response for people who would experience his buildings. Where as a young person, he was made to feel small, unseen, overpowered, unwelcome; he endeavored to create spaces where people felt, in his words, serenity, surprise, and delight.

In terms of iconic architecture, obviously the most iconic is the WTC. The symbols we create become the symbols we are beholden to and he would have been devastated to watch his most “iconic” building, the WTC, become a piece of pro-war propaganda for the war in Iraq.

I wish my grandfather had been able to do the works that were less globally recognizable and more locally beloved. The McGregor Memorial. The World’s Fair Science Pavilion in Seattle. Temple Beth-El. Robertson Hall at Princeton. Those buildings represent him best as an artist and human but might not be considered by the mainstream as iconic. I would want to free him of the burden of needing to be famous and leave him to do his most connected, humanist work.

TW: What is your favorite piece of architecture your grandfather created?

KY: McGregor Memorial Conference Center at Wayne State University in Detroit. His memorial was there, I was married there, and in a couple of months I’m excited to share this new book with a bunch of Detroit city kids at an event there. To me, it best represents the spirit of his work.

I also loved his home. I don’t know why he wanted to move to Bloomfield Hills in the 70s when they built there. He had been redlined out of that town, for being Japanese, when they had first relocated to Michigan. But he built his home there anyways, and we have wonderful memories of being all together in that house for many, many years.

TW: Why do you think peace is a big theme in the book?

KY: Our grandfather wanted to create spaces of peace that would be a respite from the chaos of daily life and our urban landscapes. I think sometimes we strive to create peace in our environments so that it might bring us peace inside, while also growing peace on a great scale. Growing up Asian in this country can be a physically and emotionally violent experience and I imagine that as much as he was striving to create environments of peace for the public, he was always on a personal quest for peace as well.

TW: Since you have written a number of books now and are also a muralist, do you find that there are any recurring themes in work?

KY: There are several recurring themes in my work, and in both my books and murals I am always trying to elevate stories of everyday people that too often go untold. Generally, my work is about the depth and humanity of everyday people. Bigger themes that contextualize the stories include justice, community, civil liberties, sovereignty, incarceration, diversity, and connectivity.

TW: How has your family inspired your artistic and creative endeavors? Do you have any other role models in the worlds of literature and art? Also, did your own cultural background influence your works?

KY: My mom is a lifelong kindergarten teacher and our rambling, old home was a free space of creativity. We painted murals on our windows, did sewing projects, baked bread in the shape of animals, and made brick and mud mortar forts. Both sides of my family overflow with lifelong activists, teachers, and artists, so I am just one of a bunch of people in my family who make work and tell stories and what I do is basically an extension of my family on both sides. I do not take for granted that I have always felt profoundly understood and appreciated artistically by my family and have always been encouraged to pursue my own way of art making. I know that is a privilege and a gift.

I found my way into children’s books through my beloved Aunty Carol. I was starting to consider art as a career, but I didn’t know what I would do with it beyond knowing that the gallery world was not for me. She introduced me to her longtime friend and Tai Chi companion, Ed Young, who was looking for someone to catalog the artwork for his, at that time, 80+ books for children. I lived with Ed and his family for a summer while I was in college and it set me on my path. It was the lightbulb moment of knowing exactly what I wanted to do.

I also had the opportunity in graduate school to study with Leo and Dianne Dillon and Marshall Arisman who were all spectacular teachers. That said, the majority of my other teachers have been my partners in my mural projects. My collaborators who I have found in schools, prisons, museums, housing occupations, hospitals, and after school programs for 20+ years.

Being Japanese-American and mixed race (my mom is French-Canadian and Irish), I have always tuned into how stories from both sides relate to the world we live in today. In particular, the mass incarceration of the Japanese-American community has inspired a lot of the work that I’ve done over the past 10+ years working with people and communities impacted by incarceration, both inside and outside of correctional facilities.

TW: What have been some of the most interesting or unexpected comments and reactions you have received from readers about Shapes, Lines, and Light?

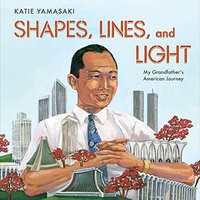

KY: I haven’t heard too much yet because the book has only recently been released, but what matters most to me is that my family connects with the book and feels that it honors our story. So far, they do. But more than any review, I care that it means something to them because our grandfather’s story is not mine. I just have the platform and I just hope that I’ve used it in a way that resonates with my family.

TW: Is there anything else you would like to share with the readers?

KY: I worked on this book during another brutal time in Asian-American history. It was triggering to be working through my grandfather’s experiences with Anti-Asian hate while so much was happening in real time around the country. I was glad to see this finally come into the public consciousness, since these acts and sentiments have been around as long as Asians have been in this country. But it was appalling to see the profound lack of societal evolution from his early days till now in this regard.

I hope that this book can be added to the cannon of books and media used to teach more, tell more stories, and in general, prohibit the continued invisiblizing of people of color, poor people, gender expansive people and everyone else living at the margins.

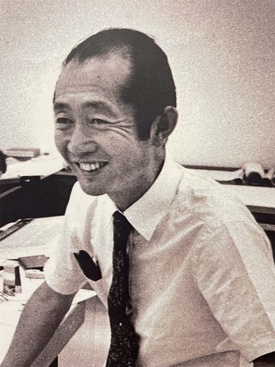

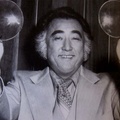

(*All photos courtesy of the Yamasaki Family)

Acknowledgement: Thank you to Katie Yamasaki for taking the time to do this interview and discussing her new book Shapes, Lines, and Light, as well as share the her family photos. Thank you to N. N. Norton Publishing for providing a review copy of Shapes, Lines, and Light for me to read and review.

* * * * *

Author Discussion—Shapes, Lines, & Light with Katie Yamasaki

Japanese American National Museum

December 3, 2022 from 11 a.m.

Join author Katie Yamasaki as she reads from and discusses her newest picture book that celebrates the life of her grandfather, the acclaimed Japanese American architect Minoru Yamasaki. She will also lead a short interactive art activity connected to the story.

For more information & RSVP >>

Shapes, Lines, and Light: My Grandfather’s American Journey is available at the JANM Store.

Katie Yamasaki is an author who has written a number of children’s books that focus on a wide variety of topics to help children understand the world around them. She is also an artist who makes murals for all with the same themes as her books.

© 2022 Taylor Wilson