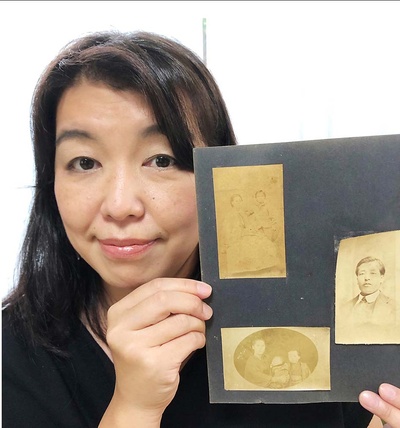

In past Japanese American historical documents, Nami is only mentioned as Sakichi Yanagisawa’s wife. But she had her own story, and above all, she was one of the pioneer women of early Japanese immigration in North America.

An 1869 document provided by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs lists a group of travelers who were issued passports and are believed to be the Wakamatsu colonists. Among the group, there is Nami’s name.

A Nichibei Shinbun article published June 24, 1934, includes an interview with Nami’s daughter Yone. Yone said that Nami returned to Japan to give birth to Yone because there were no good doctors and midwives in San Francisco at that time. After the birth, she returned to the U.S. a few months later with Yone.

Six years later, Nami returned to Japan again to give birth to a baby boy. She named him Sentaro, but he died at a young age. She returned to Japan each time for the birth of two more boys after that, but they also died.

When Yone was six years old, Nami and Yone were baptized at the China Mission in San Francisco by Dr. Gibson, like Sakichi. Nami worked as a cook at a mansion in Oakland and later worked as a housekeeper at a Japanese boarding house in San Francisco.

Then one day, tragedy happened.

Tragedy at the End of Madness

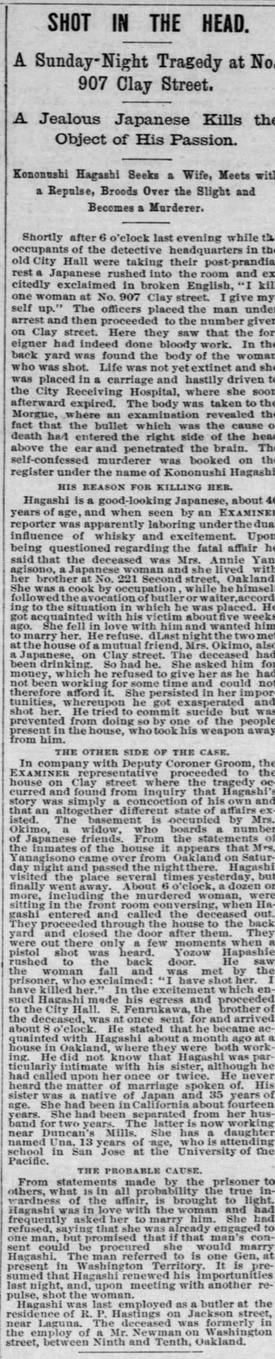

On Nov. 7, 1886, a man surrendered himself to the San Francisco Police Department.

“I killed a woman at 907 Clay St.,” he said.

The incident occurred at the boarding house in San Francisco at 6:30 p.m. on the same day.

When the police arrived at the scene, they found a woman lying in the backyard with a gunshot wound to the head. The woman was immediately taken to the hospital, but was pronounced dead shortly thereafter. According to the autopsy results, the cause of death was brain damage from the gunshot.

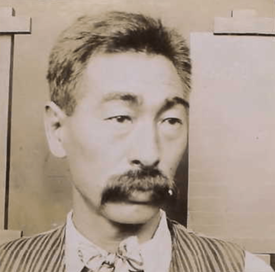

The perpetrator was a 30-year-old Japanese waiter. His name has been written in various ways due to misspellings, probably because Japanese names were unfamiliar to Americans at the time, but he corrected the true name in court as “Konomashi Hagashi,” so I will use Hagashi here.

He had fallen into madness after being rejected by a woman he had a crush on.

On the day of the incident, Hagashi had visited the boarding house several times. He left for a while, but at around 6 p.m., the bell rang.

“I want to see Mrs. Yanagisawa on important business at once,” he said.

Nami, who had been in the boarding house since the day before, was in the basement with other residents, but Hagashi called her and they went out to the backyard. Just a few minutes later, a gunshot rang out. When the residents rushed to the backyard, they found Nami lying on the ground.

“I have shot her. I have killed her,” Hagashi was said to be shouting loudly.

Local newspapers reported this incident. The San Francisco Examiner and San Francisco Chronicle reported the testimony of a witness and Nami’s brother soon after the incident.

Nami’s younger brother said that he met Hagashi about two months earlier while working as a gardener in Oakland. He didn’t know how Hagashi got to know Nami or if they were particularly close, but it seemed that he visited her once or twice.

According to the 1900 census, the koseki and other documents that were found this time, Nami’s younger brother is believed to be Seigoro Furukawa. He and his wife Yoshi had a son, Gentaro, who was born in 1875 and they also came to California.

Nami was 35 years old at the time of the incident and lived with her brother in Oakland, while her husband worked at Duncan’s Mills, Sonoma County, and they lived apart for about two years. Her brother said that Nami and her husband were not divorced, so her husband must be Sakichi.

It seems that there were other men who were attracted to Nami, a beautiful Japanese woman living apart from her husband.

Hagashi had a one-sided love for Nami and wanted to marry her, but she wouldn’t accept it. And then he pulled the trigger. It was a sudden tragedy caused by the man’s madness.

At the trial, Hagashi was sentenced to imprisonment for life at Folsom State Prison. According to prison records, Hagashi’s sentence was commuted to 20 years on Dec. 13, 1894 and he was released on May 22, 1899.

At the time of the incident, Nami’s daughter Yone was 13 years old and attended school in San Jose. Two letters from Yone were found in Nami’s possession.

Nami had been working hard to raise her child in a foreign country, hoping to give her a better education, but she never saw her daughter’s future growth.

Nami’s Final Resting Place of America

Nami’s final resting place is now believed to be at Greenlawn Memorial Park in Colma, a town just south of San Francisco.

According to the Greenlawn, Nami was originally buried in the International Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF) Cemetery in San Francisco. However, in the 1930s, the IOOF cemetery and three other cemeteries were moved from San Francisco to Colma and she was presumably reinterred at that time.

Today, Greenlawn has a section where the graves were transferred from the IOOF cemetery and there are about 26,000 graves in this section. There is no headstone for each deceased person, only a memorial cenotaph. It is quite difficult to identify her location to mourn for her, but we will never forget she was one of the Wakamatsu colonists, one of our pioneers who came to America aiming for a new life.

*This article was originally published in the Rafu Shimpo on January 13, 2022.

© 2022 Junko Yoshida / Rafu Shimpo