Throughout the postwar years, up until the late 1960s and 1970s, there was a relative dearth of Japanese American literature in general, and while the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements drew much attention in the Japanese American press, they exerted little discernable influence in the Japanese American literature that appeared during this period.

One partial exception can be found in the regular contributions of Joe Ide (also known as "Joseph Patrick Ide" and "Joseph Ide") to the Rafu Shimpo holiday editions. Ide lived in south Los Angeles and worked for the All Peoples Christian Church/Center from 1951 until his retirement in 1984, becoming executive director in 1977. Throughout that period, he contributed annual stories to the Rafu holiday edition, most of which were autobiographical pieces or pieces about his family. Since he lived and worked in a multi-ethnic area that included African Americans, African American characters turn up on occasion in his stories.

A particularly interesting example comes from his 1969 contribution, "When I Was 21… Was It a Very Good Year?" Inspired by one of his sons turning twenty-one, Ide reflects on the very different world he and his peers faced when they were twenty-one. He also tells the story of one of his son's classmates, a young African American man named Mack, who had been "quiet, unobtrusive, and never spoke unless spoken to," but after two years of college and involvement with African American student organizations, had transformed into "an angry activist, a militant among the black students." Ide also uses Mack as a foil to his son, contrasting the former's race-based dilemmas—which he implies are similar to the ones Nisei once faced—to the more universal issues of education, occupation and dating/marriage that his son faced, suggesting that Sansei did not face the same sorts of racial issues as African Americans or Nisei. Many years later, one of Ide's sons—who also goes by "Joe Ide"—became the author of a best-selling series of crime novels whose protagonist is African American.

By contrast, a 1960s Nikkei novel with African American characters, Kazuo Miyamoto's Hawaii: End of the Rainbow, reads as if such social movements hadn't occurred at all. There is some explanation for this, however: Miyamoto, an older Nisei (born in 1897) who was a physician from Hawai`i, began writing his autobiographical novel while incarcerated in various American concentration camps during World War II, with the sections involving African Americans taking place in the 1920s.

In the novel, Miyamoto's alter ego and protagonist, Minoru Murayama, attends medical school at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri from 1924 to 1927. He is one of seventy-five students, and the only one who isn't white. Minoru initially enjoys the "the open-heartedness and the geniality of his [new] friends" and notes the "goodwill among all." He also professes to being intrigued by the African American community in the city and to being "a great admirer" of Booker T. Washington. He is thus taken aback when his genial lab partner Mullinex expresses overt hostility to African Americans and tells him about having watched a lynching in Columbus, stating that "The only good n… is a dead one!" While Minoru makes it clear he disapproves of such attitudes, he also explains how it may be understandable, noting that newly arrived African Americans who migrated to St. Louis from more restrictive Southern locales "would become cocky in his exercise of this freedom," thus irritating whites. (Miyamoto makes no mention of the giant anti-black pogrom in neighboring East St Louis that had occurred less than a decade earlier). It is an oddly anachronistic passage in a novel published in 1964, particularly since Miyamoto writes that one of his goals in writing was so that "America may not repeat the gross mistakes of the past."

In his time in St. Louis, Minoru also has many first-hand encounters with African American patients and medical staff. During a stint in the Negro ward of a local hospital, he encounters "a large mulatto" patient who is initially hostile, but whom Minoru wins over in the course of his three-week stay. Later, he describes an encounter with "a very intelligent looking, clean-cut young patient" named Brown, who is a Pullman waiter. Upon finding out that Brown had gone to medical school, but had dropped out of the medical profession due to the discrimination he faced, Minoru proceeds to chew him out for "shirking" his duty to his people. Later, in describing obstetrical training, Minoru notes that "all students preferred Negro homes to those of poor white people," since they "were more grateful and cooperative" and that the homes were cleaner. After he graduates, Minoru tries to secure an internship, and encounters racial discrimination for what he claims is the first time. Here, he finds common ground with the African American (and Jewish) doctors who are limited in the number of hospitals they could potentially work for. Along the way, he visits a "Negro" hospital in St. Louis and finds that members of its staff "were excellent in any company." Over his four years in St. Louis, Minoru seems to gain a better understanding of the plight of African Americans, and in the end, comes to identify with them to some degree when he too faces racial discrimination as a Japanese American.

A later work that shares some characteristics with the sections set in St. Louis from Hawaii: End of the Rainbow is Clifford I. Uyeda’s memoir Suspended, published in 2000. Uyeda describes how he spent the World War II years studying medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans, as he faced educational discrimination on the West Coast. While he was accepted as “white,” Uyeda remained disturbed by the prevailing racial segregation as unjust and irrational. Uyeda describes a conversation he had with a black student at his workplace. The student explains that he wishes to teach American history and intends to enroll at a Northern university where he can be free from Jim Crow, and Uyeda sees the parallel with his own move from the West Coast.

Meanwhile, another novel by a Hawai`i Nisei, published eight years after Hawaii: End of the Rainbow, parallels Miyamoto’s work a different way. Jon Shirota's 1972 novel Pineapple White is also about a Japanese American from Hawai'i who finds himself on the continent, where he encounters racial attitudes that are alien to him. But this time, the author largely plays off these encounters as comedy.

Pineapple White follows its protagonist Jiro Saiki, a sixty-five year old Issei former plantation worker, as he journeys to Los Angeles from Hawai'i in 1949 to live out his retirement with his son and daughter-in-law. The story centers on Jiro's bewilderment at big city life, and much of his puzzlement stems from the racial composition of Los Angeles vis-à-vis what he is used to in Hawai'i. On a drive with his son Mitsuo when he first arrives, Jiro remarks that there are "So many Kanakas," using a colloquial term for Native Hawaiians. His son is amused by this, telling the old man that "They're not Kanakas… Negroes." Jiro replies, "They sure look like Moku's children in Waipahu." His confusion about race continues throughout the novel, as he insists that a Latino cab driver he encounters—along with essentially anyone with darker skin—must be a "Kanaka." When asked by his son's white mother-in-law if there are many African Americans in Hawai'i, Jiro replies "Maybe, Maybe not." "Rotsa black boys down Waikiki Beach." When she replies that Native Hawaiians are not the same as African Americans, he replies "What difference?... Some Kanaka more black than Negro, some Japanese more black than Kanaka."

The ever-amiable Jiro interacts with a number African American characters in the book and forms a friendship with Sammy, an African American newspaper seller in Little Tokyo. Implicitly embracing Jiro's naïve but open-hearted acceptance of everyone he encounters, Pineapple White conveys the message that African Americans should be accepted like anyone else.

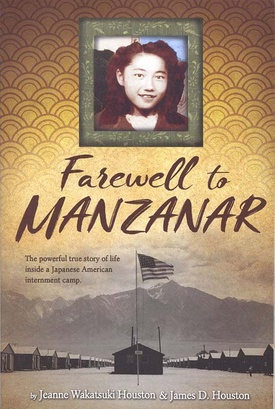

The following year saw the publication of Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James Houston's Farewell to Manzanar, perhaps the most widely read book on the Japanese American incarceration written by a Japanese American. Written from the perspective of an adult looking back on her childhood spent in part incarcerated at Manzanar, the book contains a passage that recalls a neighbor at Manzanar "with light mulatto skin." Young Jeanne played with the woman's adopted daughter in camp and noted that she was "taller than anyone in camp" and "wore an Aunt Jemima scarf around her head." The adult Jeanne comes to the realization that the woman was in fact African American and that the covering of her hair was part of her effort to pass as Japanese so as to be able to stay with her Nikkei husband and child.

To be continued ... >>

© 2022 Greg Robinson, Brian Niiya