On Feb. 19, 2022, Thomas Yoshioka will be 101 years young. There’s not much to his secret, he says. He simply states that his parents lived long—one of them into their mid 90s—and that he uses a pedal cycle almost every day to keep fit. Other than that, he shrugs at the initial look of surprise that most people give him and his son Jim Yoshioka—Thomas’s caretaker —who’s usually always by his side.

“We’re probably going to do a Zoom call with relatives and some cake to celebrate,” said Jim behind his face mask during the cover shoot for The Hawai‘i Herald. “Our family will be happy to see him.”

The pandemic and thousands of miles have separated Thomas from his roots back in San Jose, California, but he finds living on O‘ahu with his son, since July 2021, “very pleasant.”

“[My family and I] joke that Dad spent his first 100 years in California and his next 100 will be in Hawai‘i,” said Jim with a smile.

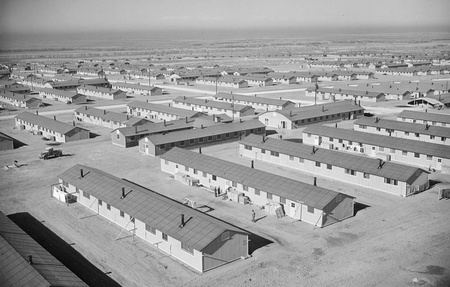

Though it’s apparent that Thomas has lived a long life, the experiences that he and his family have endured seem to belong to someone who has lived much longer. The Hawai‘i Herald learned of the Yoshioka family story while on assignment at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s John Young Museum of Art. On display that fall 2021 were prints of Dorothea Lange’s War Relocation Authority assignment, which were raw stills that captured the life of Americans who were captives under government authority due to their Japanese ancestry.

Jim—an event coordinator at UH Mānoa—had learned of the display through on-campus news and wanted to bring his father to the exhibit. When asked at that time if they had any connections to the pictures that they saw on display, Jim shared his family’s unique ties to the Japanese internment camps and how generous acts of kindness for both sides of his family at that time helped save them from losing everything.

Thomas’s memory of the time period may be slightly fogged but he’ll probably never forget that he shares his birthday with a poignant time in U.S. history. That Feb. 19 marks 80 years since President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, forcing the removal of American residents of Japanese ancestry from their deeply rooted homes to dusty barracks behind barbed wire fences. Eighty years filled with stories of hardship and resiliency for so many Americans, which resulted in lives forever altered, some lost, and an apology and a miniscule amount of reparations that came 40 years too late.

So much time has passed and yet 80 years later there is still work to be done. The coined term #StopAsianHate still had to be reminded and become viral in 2021 to increase awareness of the uptick in hate crimes against Asians Americans.

Though they were hesitant at first to be interviewed, mostly because Jim said his dad doesn’t like the “fuss,” the Yoshioka’s agreed to share their family’s story of a strong and supportive community that rallied behind them and many other Japanese American families in hopes to inspire others to work through their differences and “recognize our common humanity.”

This is their story.

* * * * *

The Escape and Internment

On Feb. 19, 1942, Thomas turned 21 years old. He was the son of Magoichi and Tsuru Yoshioka, who were ground crop farmers in San Jose, California. His parents came from Hiroshima, Japan, in hopes of pursuing a better life for themselves. A typical “American dream” story, familiar to many people and families at that time, where hard work is rewarded no matter who you were or where you were from.

Those American ideals and values were crushed when the United States was bombed by Japan’s empire and thrust into the second World War. Anger and prejudices were taken out on Japanese Americans. The final affirmation that not everyone could call themselves an American at that time was on the same day as Thomas’s birthday, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered all those of Japanese ancestry living within the western region of the United States be sent to an internment camp.

“We didn’t want our parents to have to go to the camps,” said Thomas during a Zoom call with The Hawai‘i Herald a few weeks prior to the photo shoot. His parents were of retirement age and the family feared that they wouldn’t do well there.

Soon after Executive Order 9066 was issued, Harry Yoshioka, Thomas’s older brother and the second oldest sibling, took the family car and drove east to scout another place of residence where the family could live. Once they decided on land south of Murray, Utah, Harry drove back to help pack up his siblings and whatever belongings could fit in their car, before heading back. Jim said the family then had their parents take a train to where they were so that they could avoid the long car ride.

After they lived in Utah for a bit, then Fort Collins, Colorado thereafter, they decided to move to a farming community north of Denver. Their new residence, 1,200 miles from home, is where they lived and worked, unsure of when they would or could return.

Jim’s mother, Kiyoko Asai, who was 13 at the time of the executive order announcement, had a different experience. She and her family—which included her father Seiichi, mother Shizuka, brothers Hideo, Yoshio, Hiroshi, Kiyoshi and his wife Shizuye (Susie), and their daughter Miye—were sent from their tight-knit farming community of Cortez, California to the Granada War Relocation Center, known to its survivors as “Camp Amache,” located in southeast Colorado. Kiyoshi, the eldest sibling, had his own space with his family, but Kiyoko, her parents and three other brothers lived in a cramped space no bigger than a living room. Although her father, and brother Kiyoshi, used scrap wood to turn some of the beds into bunk beds so that they could have more room to walk, it was still close quarters.

Other than a pot bellied stove to provide warmth during the cold winters, not much else was given to their family and other families that lived within Camp Amache. Winters were bitter cold and there were dust storms everywhere. Privacy was nonexistent as everyone had to share a common bathroom space with no doors, and for Kiyoko, being a teenager at the time, her changing body and new living arrangements were hard adjustments to make.

“Being sent to camp made her feel small,” said Jim as he read through notes he wrote back in 2012 when he last asked his mother what life was like for her at Camp Amache. “She also said, since the walls within the barracks didn’t go all the way up, you could hear everyone so you really had to be quiet in order to not disturb others.”

Snippets of normalcy were found in Kiyoko’s friends that she had made prior and during her time in camp. Her father and brother continued to do carpentry and repair work and got paid $20 a month while Hideo found work in the camp hospital. They also grew watermelon and tomatoes in the back of the barracks during the summer season. And because their neighbors, friends and mostly the entire Cortez community were of Japanese ancestry — and also sent to Camp Amache — the Asai family felt, in a way, some comfort while far away from home.

However there was still barbed wire fences that kept them from leaving; a constant reminder that they were deemed un-American, despite the fact that people like her brother Hiroshi Asai volunteered and served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. They were still prisoners of war and, according to Jim’s notes — even though he emphasizes that his mother and the rest of the Asai family didn’t like to focus on the negative aspects of their time in camp — it was still “not a nice place to live.”

*This article was originally published in the Hawai'i Herald on February 18, 2022.

© 2022 Kristen Namoto Jay / Hawai'i Herald