Karen Maeda Allman is the most prominent Japanese American promoter of books in the Greater Seattle area. During the 22 years she has worked with The Elliott Bay Book Company, she has promoted scores of Asian and diverse authors – from little known authors to authors who went on to become Nobel laureates. As a mixed-race white and Japanese American woman who is gay, she has overcome her own challenges while never losing her thrill and enthusiasm when she discovers a new author. Here is her story.

* * * * *

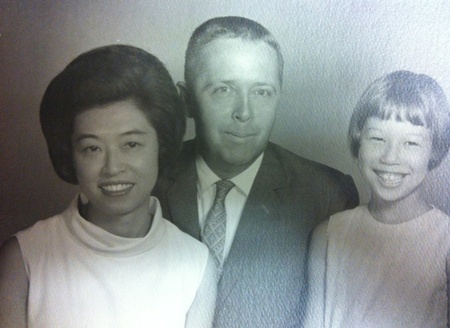

Let’s start with your parents. Your mother was born in Japan and met your Caucasian father while he was in military service. Tell us about them.

My mother grew up in a tiny rural town near Ise in the Kansai region. Everyone stayed in the area, farmed the land, and had an arranged marriage. I can’t imagine that anyone predicted that my mother would move to the big city (Tokyo), then meet and marry an American.

My parents, Joseph and Toshiko Kay Allman, married in Kobe and moved to the U.S. in 1957. This was after Congress passed the McCarran–Walter Act, which made it possible for people of Asian descent to become naturalized U.S. citizens. Interracial marriages were still illegal in about half the states in the U.S. and so my parents were posted to Kansas, a state where their marriage would be legal. (Later, I learned much more about this after reading the play Tea, produced in Seattle in 1995 by playwright Velina Hasu Houston, which tells the stories of some of these couples.)

We left Kansas for Okinawa, then settled in Phoenix, Arizona, which is where I grew up as an only child. For many years, my mother did alterations at a boutique dress shop. She was very stylish and had studied dressmaking in Tokyo and she could look at an outfit and make an exact copy. I always found that amazing!

My parents both spoke English and Japanese and my father also went to Japanese language school, where he learned to read and write Japanese, then worked alongside many Military Intelligence Service veterans in Okinawa after World War II.

However, they spoke less Japanese after my American elementary school told them I would have difficulty in school if they raised me to be bilingual. Of course, we now know that isn’t true, but like many Japanese American children, I never learned to speak Japanese.

At times, life was hard for my mother as a Japanese ex-pat. Interracial marriages had become legal in Arizona only a few years before they moved there. A Japanese American man from Tucson and his white fiancé had worked with the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) and successfully challenged the anti-miscegenation law.

It was not such an enlightened time. My mother was annoyed that whites didn’t seem to know the difference between Japanese and Chinese culture. She faced prejudice because people assumed that, because of her accent, she was uneducated.

I was asked at school if my mother was a geisha or if she had bound my feet. People would stare at us and make comments. And at the time, Japanese Americans weren’t always friendly to shin-Issei either or to people married to non-Japanese.

Yet, after they had lived in the community for a while, my parents were gradually accepted and made many close friends.

My mom died in 2012 and my dad in 2016. They never left Arizona, as for them, that was home.

Your father was very active in Japanese American redress and community work in Phoenix. Please tell us about his work.

My dad was deeply affected by the conditions of the incarceration camps after visiting a friend who was a guard at the Tule Lake camps, California, and seeing the conditions there.

During the organizing to seek redress from the government for the illegal incarceration during the 1970s-80s, my dad and his friend, Mas Inoshita, traveled around the Phoenix community speaking to any group, radio station or school who would host them. They both thought that two veterans, one white and one Japanese American, would have more of an impact as they tried to help people understand the deep injustice of the Japanese American incarceration and the need for a public apology and redress.

Mas had been incarcerated at Gila River, a camp located on the Gila River Indian Community’s reservation, near Phoenix, and he and my father worked for years to develop a relationship with this community. They joined the Ira Hayes American Legion Post on the reservation and helped produce a Gila Camp reunion. For years, my dad and Mas drove out to the reservation to clean up graffiti and trash at the Gila Camp site. They’d talk with young people as many of them didn’t know what had happened there.

You are a gay person who ‘came out’ in 1978. How did it impact you then, and fast forward to today as you are happily married to your wife. Tell us a bit about this impactful journey.

One of the first people I told was my Japanese American friend, who said, “I think you can get help for that!”

It was 1978 after all. I wrote and recorded a punk rock song about this and it was a little mean, but we both hung in there and we’re still close friends. During the next ten years, I only met one Asian American lesbian (gay female).

My early involvement in the Japanese American community in Seattle was complicated and difficult as I was gay, mixed race, and not from Seattle. The community can be quite conservative and even mixed marriages were controversial at the time. But I’ll never forget people like Mayumi Tsutakawa and Bob Shimabukuro, both members of the Asian Pacific AIDS Council, who supported us and raised consciousness about HIV/AIDS at the time and marched with us in the Gay Pride Parade.

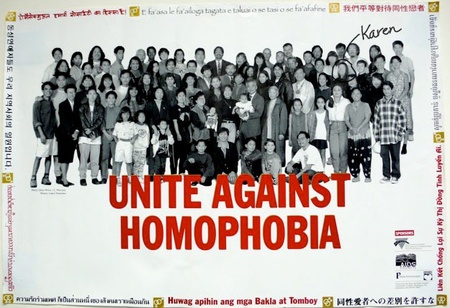

Bob, Judy Chen, Aldo Chan and others organized the “Unite Against Homophobia” poster project, which brought together many people from all sorts of backgrounds to pose for a group photo for the poster. Some of us were out, some were not. Many were straight (heterosexual) family and friends who wanted to stand by us. The posters were plastered all over the Chinatown-International District (CID) and beyond for many years. We became more courageous given that we had lost so many, so young, to HIV/AIDS during that period in time.

I never thought that marriage would be an option for me, but perhaps that was a failure of imagination. While my mother was skeptical of gay marriage and died before marriage equality legislation was passed in Washington State, she was supportive of my relationship with my wife, Elizabeth Wales.

I met Elizabeth at Red and Black Bookstore, a progressive independent bookstore on 15th Avenue East in Capitol Hill, in 1997. We got married the day after the Marriage Equality legislation was passed on December 6, 2012. She is a literary agent and works with authors, so we have a lot in common. We like to travel and we took a wonderful trip to Japan in 2019, traveling to Shirakawa-go, Kyoto, the Kiso Valley and my mother’s family’s home in Mie. Elizabeth has two children and they and their families are an unexpected gift. I love our two grandchildren who call me Ba-chan.

*This article was originally published in the North American Post on January 28, 2022.

© 2022 Elaine Ikoma Ko / The North American Post