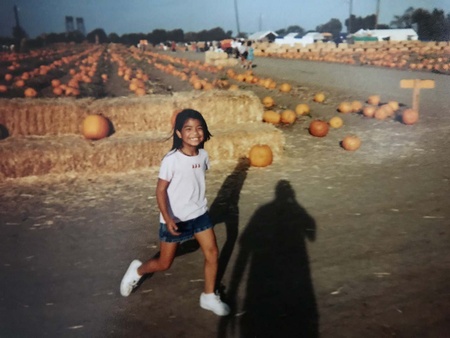

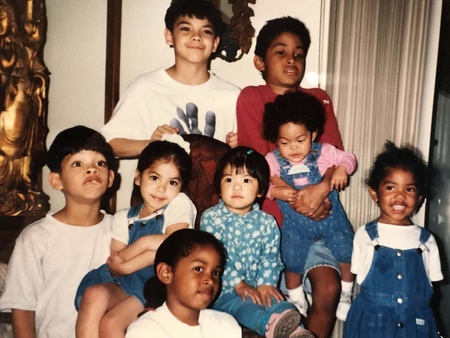

Emily Teraoka grew up around both the Japanese and Mexican cultures that are part of her heritage, but they were sprinkled into a mix of quintessentially American things—country music, pickup trucks, weekend sports, and big Halloween parties around her family’s home in Fresno, California. It wasn’t until college that she began exploring her yonsei Nikkei identity. Today, she is Lead Park Ranger for Minidoka National Historic Site, where she has the opportunity to build relationships and inspire conversations about the legacy of the WWII incarceration camps.

Discover Nikkei reached out to Emily as part of the monthly Inspire Forward series, profiling young leaders in the global Nikkei community.

Background

Emily grew up in California’s Central Valley, where her family has lived for four generations. Of mixed Japanese and Mexican descent, both sides of her family immigrated to the U.S. as farmers and farm laborers in the early 1900s. “My dad is full-Japanese third generation,” she says, “while my mom is half-Japanese (second generation) and half-Mexican. Her mother immigrated from Japan in the 1960s after marrying my grandfather.” The two of them met while her grandfather was stationed in Japan after serving the Korean War.

There was some Nikkei influence in Emily’s life growing up in Fresno. They sometimes ate Japanese food at home and watched Studio Ghibli movies (honestly, who doesn’t), and went to obon festivals, but they “did not have a strong connection to the larger Nikkei community.” This changed when she moved to Los Angeles at 9 years old, and again later when she went to college.

Larger numbers of a community do not necessarily guarantee a feeling of belonging. In Los Angeles, there were many second generation Asian Americans in Emily’s school, but she quickly found that the Asian American cultural identity there was tightly intertwined with expectations of “strict parents, intense academics, white collar careers,” and the pressure to excel in school. “There as a lot of pressure to conform to that specific version of Asian America. Being a mixed-race, monolingual, fourth-generation American with a (then-undiagnosed) learning disability, I couldn’t meet the expectations, so I took it as a personal failure. My mental health suffered as a result,” and she struggled with her racial identity.

College was the first place where she felt open to exploring her Nikkei identity by joining an Asian American club and taking classes on race and race relations. After earning a B.A. in English and MFA in Creative Writing, she found her way to public service through an internship at the Minidoka National Historic Site in Idaho.

Connection to WWII Nikkei History

Although it is a relatively young National Park Service (NPS) site—rangers have only worked there since 2017—Minidoka holds a critical place in U.S. Nikkei history. It was one of ten incarceration camps for Japanese Americans during WWII and operated from 1942-1945. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which allowed the secretary of war to begin forcibly removing Japanese Americans and Japanese from the West Coast. In total, over 120,000 Japanese Americans were held in one or more of ten camps. Over 13,000 people were jailed in the Minidoka camp alone over the course its three years of operation.

Emily Teraoka’s family was among those imprisoned, and it left a deep impact on them. Her father’s side of the family was imprisoned at the Jerome and Rohwer camps in Arkansas, and the Gila River concentration camp in Arizona during the war. “Most of them lost their homes and farms,” she says, “and one of my great-grandfathers died of cancer in the camp.”

Her Mexican American grandfather was also able to speak enough Japanese to build a relationship with her grandmother when he was stationed in Japan, because he had worked for Nikkei farmers as a young boy. “The family he farmed for had a son his age, so they grew up as close friends until the family was taken away and incarcerated during WWII.

Sadly, my grandfather lost contact with his friend and never saw him again.” She suspects that the trauma her family experienced in the camps was one of the reasons that Japanese culture played only a small part of her childhood, as her father’s family may have tried to assimilate into white American culture following their release from the camps.

This family history has strongly contributed to her passion for sharing Nikkei stories and building community as a park ranger.

A New Role

Emily is one of three all-new NPS hires at the Minidoka Historic Site, and together they have the responsibility to “interpret the exclusion and unjust incarceration of approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans during WWII…through education, research and historic preservation activities.” We asked Emily what she was most excited about in this role, and for her it is the chance to tell stories. She said it best herself…

“When it comes to families affected by the WWII incarceration of Nikkei, I’ve noticed a strong desire to connect through personal stories. While some families pass their memories down through the generations, there are some survivors who do not have anyone to tell their story to. And many younger Nikkei, including myself, have never met their grandparents or their families never discussed it.

Traumatic events are (understandably) difficult to discuss. Survivors may find the memories too painful to bring up, and descendants might not know how to ask questions without hurting their loved ones. But I think many Nikkei, of all generations, want to have these conversations to help them heal and to commemorate what happened—they just haven’t found an opportunity to do so yet. What I appreciate most about working at Minidoka is its power to facilitate such personal and meaningful conversations. When I meet a Nikkei visitor at the site, I never know if I’m going to laugh, cry, swap stories about our upbringings, or re-evaluate my perspective on life.

So for those who are ready to talk, I hope that both younger and older generations can find a way to find each other.”

Thank you for sharing your story, Emily, and for your public service! And thank you for your work to inspire Nikkei of all generations to heal through storytelling.

© 2022 Kimiko Medlock