The current exhibition at the Japanese American National Museum, entitled Sutra and Bible: Faith and the Japanese American World War II Incarceration, centers on the role of religion in the wartime Japanese American experience. It follows on the work of scholars such as Duncan Ryuken Williams, Anne Blankenship, and Beth Hessel, who have shed light on such topics as religious workers in camp and religious affiliation as a means of community formation. In fact, religion also played an important and largely unrecognized role in the mass official confinement of Japanese Canadians during World War II (often called the Japanese Canadian Internment), with people being separated according to religious affiliation, and Christians receiving favored treatment over Buddhists.

For those who are less informed on the history of the wartime events in Canada, let me summarize briefly: In the first half of 1942, reacting to war hysteria and political pressure from the West Coast, Canada’s Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King successively removed 22,000 Canadians of Japanese ancestry from Canada’s Pacific Coast. First, in January 1942, the government ordered all adult males of Japanese ancestry to be sent for work in road labor camps. When this failed to satisfy West Coast business and political interests, on February 24, 1942 Prime Minister King issued Order in Council P.C. 1486, which created a “protected area” of 100 miles along Canada’s Pacific Coast, from which all remaining persons of Japanese ancestry would be excluded. The government created a new civilian agency, the British Columbia Security Commission (BCSC), to supervise and undertake mass removal.

By late summer 1942, all Japanese Canadians had been moved off the West Coast. Approximately 1000 single men were sent to work on road labor camps. Another 3500 Japanese Canadians opted to sign contracts to work on sugar beet farms outside British Columbia, where they served as exploited labor. Approximately 1,000 more affluent Japanese Canadians were permitted to settle in so-called “self-supporting projects” at their own expense.

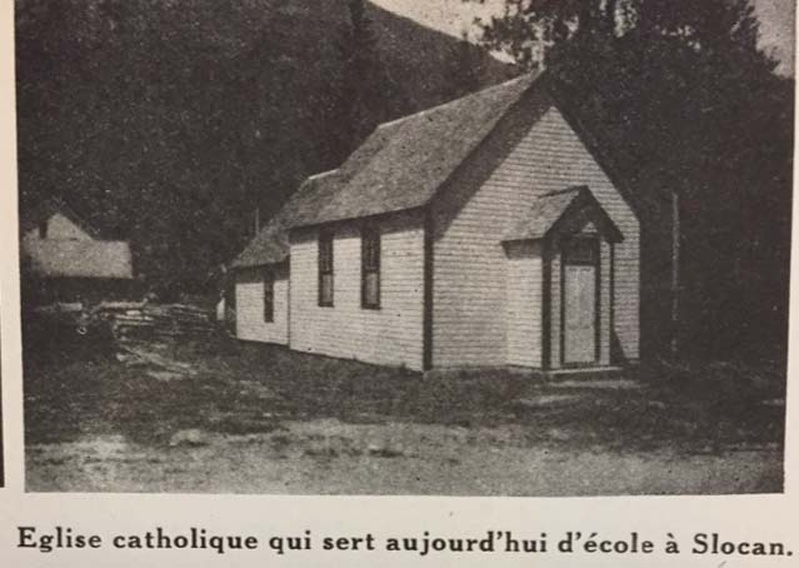

The vast majority of Japanese Canadians, over 12000 people, were sent to internal exile in B.C.’s Slocan Valley. There they were housed in what were euphemistically known as the interior housing centres, mainly in largely-abandoned mining towns, where the government refitted abandoned houses. The BCSC built one camp of shacks, which it dubbed Tashme (a combination of the first letters of the family names of the BCSC’s three directors).

The exclusion of West Coast Japanese Canadians led to a new surge of activism among Christian religious groups. First, representatives of the Roman Catholic Church in Vancouver proposed to the British Columbia Security Commission (BCSC) that the Church take charge of all Catholics of Japanese ancestry and arrange for them to move, en masse, to a Catholic-specific settlement in the interior. The Anglicans, the Salvation Army, and the United Church of Canada then joined the proposal, offering to assume control over their own communities of faithful. BCSC officials were aware that such voluntary church-led efforts would supplement their meager official budget. As a result, they acceeded in part to the request.

While they retained control over the logistics of removal, they agreed to divide inmates between different settlements based on religion, and granted each of the Christian denominations exclusive missionary privileges in its own camp or settlement. Although Buddhists represented a large majority of Issei and a sizable minority of Nisei, BCSC officials did not attempt to work out any similar arrangements with Buddhist churches.

Thus, in the process of mass removal and assignment to confinement sites, the BCSC segregated the Japanese Canadians by religion. United Church members were concentrated in the settlements at Lemon Creek and Kaslo. Confinement sites in the Slocan Valley such as Slocan City were set aside for Anglicans. Declared Catholics were sent to the Greenwood settlement. However, because of the relatively small number of Christians, each settlement also housed a large Buddhist population. Given the small number of Roman Catholics among the Japanese population, only 120 families of the 1,200 residents that were set to Greenwood were Catholic.

In addition to meeting the different spiitual needs of their faithful in the confinement sites, religious groups mobilized to open schools for children. The BCSC undertook to provide schooling only up through 8th grade, and built rough school buildings in all the settlements. However, the schooling was slipshod and poorly funded—barely $20 per student per year. More importantly, federal authorities refused to provide any funds for secondary education.

In response, Anglican and United Church authorities opened Christian schools and hired Nisei teachers to work in them. The Roman Catholic church dispatched the French Canadian Franciscan priest Father Gregoire Leger, plus a group of nuns, to come out from Quebec to the Greenwood site and open Catholic schools there. Japanese Buddhists did not have any grop of coreligionists outside to fund the opening of schools for their congregations, and were forced to recommend correspondence courses. In order to meet the needs of the Buddhist population in Slocan, Catholic Nuns from the Sisters of the Assumption under Sister Superior Marie-du-Crucifix meanwhile opened schools there.

In addition to providing assistance inside the confinement sites, church groups encouraged West Coast Japanese to leave camp and resettle in the East. At first, few individuals took the dramatc step of resettling. However, in 1944 Prime Minister Mackenzie King issued an Order-in-Council that required Japanese Canadians to relocate outside of British Columbia, on pain of being deported to Japan at the war’s end if they remained in the settlements. The order led to a mass movement of people out of the settlements. The largest fraction of new migrants, most of who were young, unmarried Nisei, moved to Ontario (though because of opposition from local whites to Japanese Canadian newcomers, Nikkei settlement within the city of Toronto remained restricted until 1946).

However, the influence of the Catholic Church was particularly apparent in the case of those migrants, approximately one-tenth of the total, who moved to Quebec. These were predominantly Japanese Catholics from Greenwood and others who had been encouraged by the Catholic missionaries.

In the end, the newcomers to Quebec settled almost exclusively in the Montreal area, whose Japanese population reached 1247 by the end of 1946 and over 1300 in 1949, making it the largest Japanese community in the Francophone world. A smaller number resettled in Farnham, in the Eastern Townships, where the federal government opened a hostel for resettlers.

As mentioned in a previous article [McGill University] Catholic and Anglican missionaries assisted refugees from the camps to settle in Montreal. Canon Percival Samuel Carson Powles, a former Anglican missionary in Japan, organized relief efforts through the Montreal Committee on Japanese Canadians. Catholic missionary groups, cut off by the war from their work in Asia, devoted their efforts to assisting Asian Canadians. Under the leadership of Mother Saint-Pierre, the Sisters of Christ the King worked to find housing and employment for the migrants. In 1945, they opened a hostel for young Nisei women. Even as Catholic groups took the lead in resettling migrants within the francophone community, a few Nisei students were admitted to the Catholic institution Université de Montréal.

Despite these efforts, the migrants faced significant discrimination in housing and employment, which church groups, whether Catholic or Protestant, made little progress in countering. A significant fraction of Issei and Nisei found work in the garment factories of Montreal’s Jewish community (who knew something about life as a minority), or were given opportunities by Jewish landlords and clients.

The support offered by the Catholic Church, in particular, to Japanese Canadian migrants to Montreal during World War II continued in the postwar era. When Father Jean-Claude Labreque returned to Montreal from a mission to Japan in 1950, he devoted himself to assisting Japanese Canadians. Out of his own pocket, he helped fund the purchase of a building on Sherbrooke Street that housed a kindergarten and French classes, and served as the first community center. Later the Grey nuns (les soeurs grises) donated land in Villeray for the building of the St Paul Ibaraki mission as a permanent community center.

When the building opened in 1964, Cardinal Jean-Emile Leger, the powerful self-described “prince of the Church,” who had served as a teacher in Japan in the 1930s, officiated and delivered a speech in Japanese. The mission later became the site of the Japanese Canadian Community Centre, which still stands. One result of the Church’s efforts was that Montreal’s Japanese community remained marked by a distinct cosmopolitan flavor.

© 2022 Greg Robinson