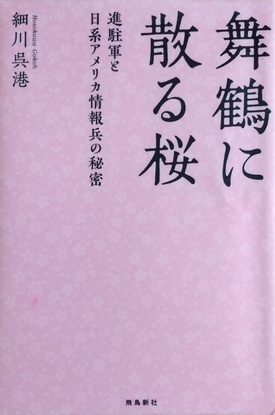

Sometime last year, I was in the non-fiction section of a bookstore when I came across a book called "Sakura Falling in Maizuru" (by Hosokawa Goko, Asuka Shinsha, published in 2020) that caught my eye because the subtitle read "The Secrets of the Occupation Army and Japanese American Intelligence Soldiers."

Maizuru (Kyoto Prefecture) is a port town facing the Sea of Japan, and is known as the gateway to Japan for Japanese soldiers and civilians who crossed the Sea of Japan after the war from mainland China, Siberia, and other places. But what does it have to do with the occupying forces and Japanese American soldiers? And what does the cherry blossom of Maizuru refer to? I read the book with interest and discovered a fact I had never known before.

According to the author profile at the end of the book, Hosokawa was born in Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture in 1944, and after working for a publishing company, he became a freelancer. He has been researching modern China, Manchuria, and Mongolia for a long time, and continues to uncover unknown people who lived in history.

In March 2018, the author learned that there was an event to plant cherry trees on a hill in Maizuru City. Nine former Japanese-American soldiers who had been stationed in Maizuru immediately after the war would be participating from Hawaii. They were former military personnel and associates who had belonged to the 100th Infantry Battalion, famous for its exploits on the European front during World War II, and the MIS (Military Intelligence Service) intelligence unit.

Why were they in Maizuru after the war, and why did they come to plant cherry trees there 73 years after the war? This book answers these questions by tracing the history of one Japanese American. Below, we will follow the main points of the book.

Thoughts of a former Japanese American soldier

After the war, 100 cherry trees were planted in a section of Kyoraku Park overlooking Maizuru Port by Japanese American soldiers of the occupying forces. Since then, the trees have grown and blossomed beautifully, but over time, the branches have withered and many trees have fallen.

A person living in Maizuru who learned about this wrote about it on his blog in 1996. People who planted cherry trees all over Japan and were also interested in Japanese people in Hawaii responded to the blog and decided to work together to plant cherry trees on the hills of Maizuru. Furthermore, former members of the 100th Infantry Battalion and MIS in Hawaii who had heard about this decided to visit Maizuru together.

But who was the one who first came up with the idea of planting this cherry tree? This remained a mystery for many years, but it was only in 1991 that it was revealed, after it was featured in a Japanese newspaper. The person in question was Fujio Takagi.

Fujio's father, Morisuke Takagi, immigrated to Hawaii from Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture, at the age of 20 in 1913 (Taisho 2). He had six children there and traveled back and forth between Hawaii and Japan, eventually returning to Japan in 1933 (Showa 8). All five of his children returned to Hawaii at the same time, but Fujio was left behind in Hawaii.

After graduating from high school in Honolulu, Fujio worked as a mechanic at a sugar factory, and then worked as a mechanic on a ship dredging Pearl Harbor. On the morning of December 7, 1941, he witnessed the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, during which he saw a Japanese fighter plane make an emergency landing on the water about 200 yards away. The plane soon sank, and the Japanese pilot aboard was floating on the water. Fujio approached to grab the man, but he soon sank underwater, so he retrieved his life jacket and other items.

There was something like a name tag sewn onto his jacket, and Fujio's comrades asked him to read the writing. However, he couldn't read it, so he was accused of being a spy, taken off the ship, and eventually fired. The frustration he felt at this time made Takagi decide to become an American, and he volunteered for the military. After two setbacks, he finally joined the MIS in 1943. After receiving intensive Japanese language training at Camp Savage in Minnesota on the American mainland, he was sent to the Pacific front.

After the war ended, Fujio was stationed in Japan, but during that time he visited his hometown of Iwakuni and reunited with his mother, whom he had not seen since childhood. Upon seeing the ruins of their house, he offered her some money, saying, "Please use this money to rebuild our house." However, his mother refused, saying, "Use that money to do something for all Japanese people."

In 1947, Fujio was assigned to Maizuru, where he and his team had a special mission. With the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union already underway, the MIS and CIC (Counter Intelligence Corps) of GHQ (General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers) stationed in Maizuru tried to find out about the state of affairs in the Soviet Union from Japanese soldiers returning from Siberia. They also tried to find those among the repatriates who had been influenced by Soviet ideology and to find Soviet spies.

The Maizuru Tourism Association has summarized the repatriates to Maizuru as follows:

"The repatriation to Maizuru Port began in October 1945, when the first repatriation ship, the Unzen Maru, arrived with 2,100 repatriates heading for their homeland. Repatriations from the former Soviet Union peaked in 1947, when 83 ships transported approximately 200,000 people and set foot on Maizuru soil. However, in 1950, repatriations from the Soviet Union were halted as people who had been captured by the Soviet Union and were being held in the freezing cold of Siberia were unable to return home. After the repatriation project was resumed, Maizuru Port continued to accept repatriates as the only repatriation port in Japan. In 1958, the last repatriation ship, the Hakusan Maru, brought 472 repatriates to Japanese soil, and the repatriation project at Maizuru Port was finally completed. In the end, Maizuru alone accepted over 660,000 repatriates..."

When Fujio was assigned to the post, the repatriation was at its peak, and he worked as the chief of CIC. During this time, Fujio miraculously met his younger brother who was among the repatriates.

Japanese people will be happy

While in Maizuru, Fujio was thinking about the words his mother had said to him, and came up with the idea of planting cherry trees. He thought, "The Japanese people would be happy." So he arranged for 100 cherry tree saplings to be sent to Maizuru, but the day after the saplings arrived at Higashi-Maizuru Station, he was transferred to another post and had to leave Maizuru. So he happened to meet some fellow second-generation Japanese American soldiers at the station and asked them to help him plant the trees. It is said that 70 cherry trees were planted on the hill of Kyoraku Park, and the rest at a nearby school. This was in 1949.

The cherry blossoms Fujio sent thus delighted the eyes of the people of Maizuru for a long time afterwards. Fujio never spoke about his act himself, so for many years the identity of the donor of the saplings was unknown, but it became clear in a 1991 article in the Yomiuri Shimbun commemorating the 50th anniversary of Pearl Harbor. In 1994, the city of Maizuru invited Fujio Takagi and his wife Yayoi, who were living in Hawaii, to visit Maizuru.

Fujio had visited Japan six years earlier, when he had tracked down the family home of a Japanese pilot whom he had rescued at Pearl Harbor. Thinking that the family would want to know about the soldier's final moments, he told them about his own experiences at Pearl Harbor.

After the war, when the Japanese people were suffering from food shortages, American soldiers asked Fujio why he sent them cherry blossoms instead of providing food. The answer to this question is probably explained by the cherry blossoms that are still loved today.

(Titles omitted)

© 2022 Ryusuke Kawai