For most of its history, the leadership of the JACL has been composed largely of men. Figures such as Mike Masaoka, Saburo Kido, and Clifford Uyeda defined the various eras of the JACL’s existence, and it was not until the election of Lillian Kimura in 1992 that the JACL had a woman president. Still, from its earliest days, the JACL has been shaped by the contributions of women. In the early 1930s lobbyist Suma Sugi almost singlehandedly won repeal of the Cable Act. In the postwar years, individual women such as Mari Sabusawa and Ina Sugihara occupied leadership roles on a local level and joined the national board, and Guyo Tajiri ran the JACL journal Pacific Citizen alongside her husband Larry.

Even more vital for the JACL were the contributions of Teiko Ishida, who helped operate the organization during several crucial moments in its history. A talented fundraiser and administrator, Ishida headed the JACL’s Salt Lake City main office throughout the first years of the war. As National Secretary from 1943 to 1945, she led public campaigns to finance the organization and promote the patriotism of Japanese Americans.

Teiko Ishida was born on April 16, 1916 in San Francisco, California to Tsunegoro “Frank” and Take Ishida. Tsunegoro Ishida was well known among Japanese Americans as one of the first “pioneers” to come to San Francisco, having arrived in 1890. The family lived in the vicinity of Japantown, on 307 Broderick St.

In 1930, at age 14, Teiko attended San Francisco’s High School of Commerce. Ishida proved to be a gifted student and administrator: at 15, she worked as secretary to the dean of boys, and during her last year she took evening classes at MacMaster-Paine Business college. Soon after graduating from both the High School of Commerce and MacMaster-Paine, she found employment as a secretary in the offices of the Pacific Steamship Company.

Beginning in 1936, Ishida became involved with the San Francisco chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League. She soon became known throughout the Bay Area as a skilled organizer. In September 1936 Ishida attended the JACL national convention in Seattle alongside delegates Saburo Kido, future National JACL President, and Yasuo Abiko, the son of Nichi Bei owner Kyutaro Abiko.

In October 1936, Ishida was elected by fellow delegates to serve as secretary for the Japanese Young People’s Celebration committee, which prepared for the future opening of the Golden Gate Bridge in 1937. As part of her work for the event, she designed a robe worn by the Queen of the parade. In January 1937, members of the San Francisco JACL chapter elected Ishida to its board of governors, alongside Kido and Abiko.

In April 1937, Ishida planned another party for the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge. As “Chairman Miss Ishida,” she earned the cooperation of Fillmore merchants. For the talent portion of the event, Ishida enlisted Watson Humphrey, an NBC talent scout; Howard Imazeki of Shin Sekai, Nichi Bei editor Larry Tajiri, and Dr. Henry Takahashi to serve as judges. The event was lauded as a success, and garnered a crowd of over 1000 attendees.

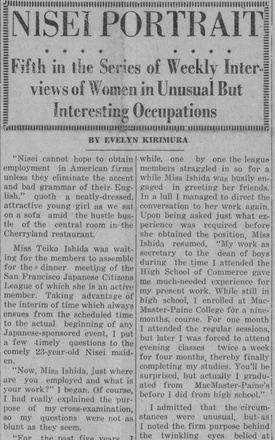

In July 1938, journalist Evelyn Kirimura interviewed Ishida as part of a series titled “Nisei Portrait,” which highlighted Nisei women in “unusual but interesting occupations.”

In the interview Ishida revealed her views on need for Japanese Americans to adapt to American culture: “Nisei cannot hope to obtain employment in American firms unless they eliminate the accent and bad grammar of their English.” Citing her own experience as the only woman at her workplace, Ishida stated that Nisei needed to be courageous and take up whatever opportunities were open to them: “What few gains a woman makes are hard-fought and she can only go so far and no more. I want to get to the top, but I’m afraid that I’ve gone as far as I can in this company. Nonetheless I intend to keep on trying. Now this is the kind of spirit all Nisei should adopt.” As evidence of her support for other women in the JACL, Ishida created and ran a Women’s Auxiliary wihin the San Francisco JACL.

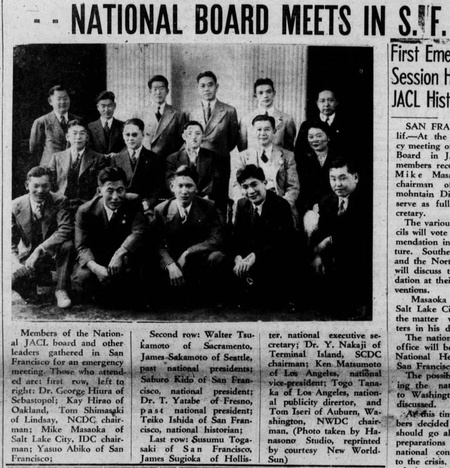

Ishida’s ambitions eventually paid off. In November 1938, JACL National President Walter Tsukamoto appointed her to be “co-chairman” of the National JACL committee and historian of the National JACL – the highest position held by a woman in the organization at the time. Although Ishida resigned from her previous position as head of the Women’s Auxiliary, she continued to maintain a presence at their various events.

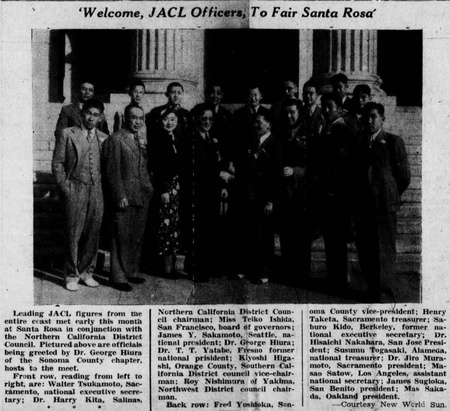

As part of her work with the National JACL, Ishida became an important figure in outreach efforts between the organization and the general public. In March 1939, Ishida organized a large event in appreciation of the schoolteachers of San Francisco at the Hall of Western States on Treasure Island (JACL leaders did not seem to appreciate the irony of celebrating schoolteachers when Nisei teachers were excluded on racial grounds from teaching jobs). Over 1000 people attended the event.

Then-San Francisco JACL chairman Saburo Kido singled out Ishida for praise, describing her as “a strong leader and a good organizer with an aggressive spirit mixed with the required initiative. The city is indeed fortunate to have such a leader.” In April 1939, Ishida appeared alongside Kay Kitagawa and Ruth Tanbara on San Francisco’s radio station KSAN. The recording, based on a script written by Ishida, Saburo Kido, and Iwao Kawakami, documented the history of the JACL and its present goals.

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Ishida and other JACL members mobilized to enlist Japanese American support for the war effort. In February 1942, Ishida joined several JACL members in persuading Issei community members to register as ”enemy aliens,” as a demonstration of their own patriotism.

Following the announcement in April 1942 that Japanese Americans would be forcibly removed from the West Coast, the JACL hired Ishida to become office secretary at the new National Headquarters in Salt Lake City. On March 29—days before the exclusion order went into effect—Ishida filled her Studebaker with the records and the files of the JACL and set off for Salt Lake City. Joining Ishida for the ride was Larry Tajiri, who assumed the position of assistant to national secretary Mike Masaoka and editor of The Pacific Citizen, and his wife Guyo.

During her time as secretary for the national office, Ishida served as the first point of communication between the JACL and outside organizations. Ishida corresponded with several university presidents, such as Remsen Bird of Occidental College, as well as Allen Blaisdell, director of UC Berkeley's International House, about the status of Japanese American students. (Sadly, because of her leadership position and ambiguous name, she was often misgendered as “Mr. Teiko Ishida” in correspondence.) She also sent reports to various government agencies, such as the Department of Interior and Western Defense Command, regarding the status of Japanese Americans in the Armed Forces.

She also wrote as a regular columnist for the Pacific Citizen, titled “Calling All Chapters,” from 1942 to 1943. Her columns summarized the news of the various JACL chapters and included updates from the National Headquarters, along with information on funding for the organization. Some of her early columns included moving descriptions of incarcerees boarding the trains for the permanent WRA camps, and was told not to state the dates of the transfers due to their classification as “military information.” Her first column in the June 1942 issue of the Pacific Citizen, and ran until 1944, when Hito Okada took over the column.

Perhaps Ishida’s most controversial decision occurred during the Loyalty Questionnaire crisis. The matter of loyalty oaths for JACL members became a significant detail of Deborah Lim’s 1990 investigation into the history of the JACL. As later revealed in Lim’s Report, in May 1943 JACL President Saburo Kido sent an internal memo to Ishida discussing the status of loyal JACL members. In the memo, Kido mentioned that he concurred with Mike Masaoka’s decision that any individuals who responded “no-no” to questions 27 and 28—the questions regarding loyalty to the U.S. and willingness to serve in the Armed Forces—should be removed from the organization:

Regarding members who answered “no,” Mike suggests that we send out a bulletin to all chapters that such members will be suspended. He believes this is necessary for our records; that is, we should be clear as to the loyalty of our members. Also we cannot accept anyone who has answered, “no.”

In response, Ishida communicated to Kido that Masaoka had agreed to the removal policy, but cautioned against sending an official bulletin to all chapters. Rather, Ishida stated, the JACL should ask the WRA to furnish a list of “no-nos”:

As far as the “no-no” ones are concerned, I don’t think we can possibly find out so the best thing is just issue the request to sign the loyalty pledge of all associated members. Then if there is a chapter, issue a special letter to the chapter that the “no-no” ones will have to be suspended until such time as the records are cleared. And if they have any reason for changing the answer to yes, possibly we can suggest to write to the WRA. It is the best that we do this and protect our position.

Kido responded that waiting for a report from the WRA would take too long. Making an executive decision, Kido informed Ishida and JACL treasurer Hito Okada that he would send out individual loyalty oaths to all JACL chapters.

On August 8, 1943, Teiko’s mother, Take, died at Holy Cross Hospital in Salt Lake City. Following her death, Teiko and her brother George, then a private in the Army stationed at Camp Shelby, attended her funeral at Topaz camp. Shortly thereafter, Ishida received clearance from the War Relocation Authority to take her mother’s ashes to San Francisco, under guard by a WRA official.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen