In the last chapter, I wrote about the NYK Seattle shipping route which made a great contribution to the development of Seattle. In this chapter, I’d like to talk about the growth of Japanese barbershop businesses in Seattle from 1918 in two parts by introducing articles about Japanese Barbershop Committee in Seattle and the Nisei who strove to start their own barbershop businesses around 1939.

JAPANESE BARBERSHOP BUSINESS IN SEATTLE

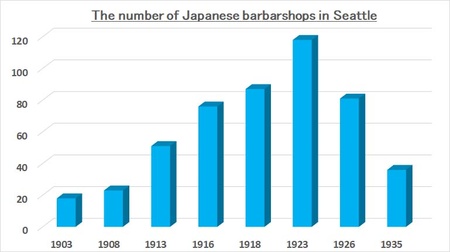

The Japanese barbershop business in Seattle experienced a large growth starting in 1910.1 In 1916, Seattle had 76 barbershops run by Japanese. In contrast, there were 325 barbershops run by Caucasians in the entire city in the same year. There was a movement by Caucasian-owned barbershops to eliminate Japanese-owned shops. Consequently, the Japanese Barbershop Committee, which was established in 1907 with Chuzaburo Ito as its head, devoted its time and effort to work in peace with their Caucasian peers. We can see traces of their hard work in The North American Times.

JAPANESE BARBERSHOP COMMITTEE IN SEATTLE

“General Assembly Meeting of the Barbershop Committee” (From the Jan. 14, 1918 issue)

“Yesterday the general assembly meeting of the Seattle Japanese Barbershop Committee started in the afternoon at the Japan Hall, followed by a New Year’s party which began at 7 p.m. There was a total of about 200 participants from the committee, including both males and females, and some guests including Consul Matsunaga, and Takahashi, Tukuno, and Kikutake from Hokubei Nihonjin-kai (North American Japanese Association). Others in attendance included Takeuchi from the Taihoku Nippo (Great Northern Daily News), Miyazaki from The North American Times, and on the Caucasian side barber examiners and vice chairpersons and their spouses. They had a banquet with catered food and boxed meals from Maneki (restaurant).

“As master of ceremony, Chuzaburo Ito introduced Consul Matsunaga, who gave his speech in both Japanese and English. Then the former examiner Ray, Chairperson of Hokubei Nihonjin-kai Takahashi, Vice Chairperson of the Caucasian Committee Ivy, Takeuchi from Taihoku Nippo, the current examiner McGauchie, Miyazaki from The North American Times and others made comments in turn. Interpreter Katayama translated English speeches into Japanese as the committee advisor and received a great round of applause each time. The banquet was followed by an after-party, where the participants enjoyed a variety of performances for which they gave a big round of applause. The level of excitement was something we had not experienced for a long time at any gathering.”

We can see that under the leadership of the Barbershop Committee, with Ito at its center, a lot of Japanese people in the barbershop business not only attended New Year’s parties, got along with their peers and formed a close bond, but they also worked hand-in-hand with their Caucasian peers to build a working environment where they could operate their businesses smoothly.

In the same issue, a section titled “What We’ve Seen and Heard” gave a detailed explanation of the Barbershop Committee.

“The Barbershop Committee currently has 175 members, 88 of whom are males and 87 are females. The number of females is just one short of the males, and the fact that they are all licensed and making a living in the barbershop business is highly encouraging. There is no other place in the United States with a Japanese barbershop committee as big and powerful as this one.

At the New Year’s party last night, the former examiner Ray sat next to me and whispered in my ear: ‘I was surprised to know that there were this many Japanese female barbers. Japanese women are prudent, immaculate and detail-oriented, so they are more popular than Caucasian female barbers. Particularly, since their hands are softer than males,’ once a Caucasian man gets his face shaved by a Japanese woman, he will become a regular for sure.’ He certainly had a point.”

From this article, we can estimate that as of January 1918, there were about 87 barbershops run by Japanese couples. My grandfather Yoemon, too, opened his shop at 163 Washington Street in 1918 and worked with his wife, and the business went well with many Caucasian customers.

“New Board Members of the Barbershop Committee” (From the Jan. 25, 1918 issue)

This issue reported on the new board members appointed at the regular general meeting held on January 13 with a list of their names. The breakdown of their home prefectures according to the directory source is as follows: 10 members from Yamaguchi, eight members from Fukuoka, two members from Hiroshima and one member from Shizuoka.

Councilor Ritsu Sato in Hokubei Hyakunen Zakura (100-Year Cherry Blossoms in North America) writes in detail about the history of hard-fought battles against the Caucasian Committee. When he came to Seattle in 1907, he started a barbershop business with the help of Ito, and supported Ito as Vice Chairperson with accountant Jitsuzo Hara before World War I. He opened a barbershop in Seattle after the war, too, but said that the world seemed to have changed quite a lot compared to his old, struggling days.

Fukujiro Iwami is another Councilor and is from Yamaguchi Prefecture. His name was on the funeral notice of my grandfather Yoemon on behalf of his friends when he died in an unforeseen accident in 1928. I also found the names of some family relatives from the same hometown as Yoemon, who were listed as board members—Takejiro Uesugi, Saisuke Yoshida, and Ryunosuke Yoshida2.

An article published on October 9, 1919 reported that a big farewell party was held at Gyokkoken (restaurant) before Saisuke Yoshida and Ryunosuke Yoshida left for Japan temporarily. Yoshida is the older brother of Ryunosuke, and he ran Oukaro (a Chinese restaurant). He was quite well known in Seattle.

PRICE INCREASES TO ALIGN WITH CAUCASIAN COMMITTEE

“Hideous Increase in Haircut Price” (From the Apr. 24, 1918 issue)

“What a bold decision to suddenly increase the haircut price from the recent 45 cents to 75 cents (50 cents for a haircut and 25 cents for a shave) overnight. We understand that the Japanese Barbershop Committee works hand-in-hand with the Caucasian Union, but there is no need to raise the price that much. We simply feel frustrated knowing that the decision was not made on their own will. We can’t avoid a price increase owing to inflation, but this is simply unthinkable.”

Forty-five cents back in the day was approximately 90 sen in Japanese currency and is about 900 yen at the current rate. Seventy-five cents was about 1 yen, 50 sen and is about 1,500 yen ($11.80) at the current rate of Japanese currency.

“Price Increase in Barbering” (From the Apr. 26, 1918 issue)

“As Committee Chairperson Ito came and told us, Caucasian barbershop owners had informed the Japanese side of their decision to set their price at 75 cents minimum. Baffled by such a sudden and big increase, he tried to negotiate, first to increase the price to 60 cents and then to 75 cents but it was not accepted. If they didn't follow the flow, Japanese barbers would lose union customers, so they had no choice but to raise the charge, knowing that it would puzzle many.”

The executive members of the Caucasian Committee showed an understanding of Ito’s suggestion, it seemed, but they couldn’t reach a consensus within the committee. The April 30 issue reported an “Independent Barber Plan” which was a movement to encourage people to leave the committee and operate businesses targeting only Japanese customers. However, in the end, to align with the Caucasian community, Ito made a tough decision and unwillingly agreed to the same price increase as on the Caucasian side.

In the Chapter 8 - Part 2, I will introduce some articles about the Seattle general strike and the Nisei who strove to start their own barbershop businesses around 1939.

Note:

1. The prosperity of the Japanese barbershop business in Seattle refers to “Yoemon Shinmasu – My Grandfather’s Life in Seattle—Part 2, Yoemon’s First Job and Life in Seattle.”

2. Ryunosuke is the father of Jim Yoshida who appears in The Two Worlds of Jim Yoshida.

References:

Hokubei Nenkan (North American Yearbook), Hokubei Jijisha, 1913.

Kojiro Takeuchi, History of Japanese Immigrants in the Northwestern United States, Taihoku Nippo-sha, 1929.

Kazuo Ito, Hokubei Hyakunen Zakura (100-Year Cherry Blossoms in North America), Nichibou Shuppan, 1969.

*The English version of this series is a collaboration between Discover Nikkei and The North American Post, Seattle’s bilingual community newspaper. This article was originally publishd on June 11, 2022 in The North American Post and is expanded for Discover Nikkei.

© 2022 Ikuo Shinmasu