The paintings of Dr. Henry Shimizu, retired Edmonton Nisei plastic surgeon, were presented in a show at the University of Victoria’s (UVic) Legacy Gallery entitled Isshoni: Dr. Henry Shimizu’s Paintings of New Denver Internment that brought together Nisei Dr. Shimizu, curators Yonsei Samantha Kuniko Marsh (Vancouver, BC), and Sansei Bryce Kanbara (Hamilton, ON).

Well timed during this year, the 80th anniversary of the internment, one might wonder: How are we Japanese Canadians going to remember the internment and, importantly, how do the stories of internment resonate with younger generations? The theme of this exhibition presents a great launch pad for these kinds of family discussions.

The paintings of Dr. Henry Shimizu were based on real pictures from family, friends, and his memories of being a teenaged internee in New Denver. Dr. Shimizu has been active in the JC community for decades including a stint chairing the Japanese Canadian Redress Foundation (1989-2001) and being awarded the Order of Canada (2003), the country’s highest award. His remarkable life spans unimaginable times of hardship and racism, overcoming it all to become an esteemed plastic surgeon.

Curator Yonsei Samantha Marsh, an American Nikkei, hails from San Francisco and was educated at the University of British Columbia (Anthropology) and University of Glasgow (MSc, Museum Studies). Since 2020, she’s been the program coordinator of the Vancouver’s Powell Street Festival.

Samantha shares her family background:

“My mother is Sansei and also grew up in California....My maternal grandmother (Mary Tsudaka, b. Bonners Ferry, 1938) grew up in Idaho, and her’s was the only Japanese family in their town. During WWII, her family’s assets were frozen. This prevented my great aunts from attending university, and the family was forced to borrow money from neighbours to keep their laundromat business running.

“I found out recently that my great-grandpa, Fred Motoshi Tsudaka, (b. Okayama, 1887; d. January 27, 1944 [pneumonia]) worked in Canada on the railroads before settling in Idaho. My maternal grandfather (Aki Shishido, b. Ola‘a, HI, 1933) grew up in Hawaii on the Big Island. As a child, he worked on a sugar cane plantation. He later registered with the military which allowed him to go to St. Louis to become a dentist.

“My grandfather’s parents came from Aizu-Wakamatsu (Fukushima prefecture) and Hiroshima or Yamaguchi prefecture.”

Recalling her early experiences participating in the Japanese American community, she says: “I found that growing up in San Francisco, I was surrounded by visible celebrations of Japanese American arts and culture. As a child, I remember visiting Ruth Asawa's public sculptures throughout the city, volunteering at the San Francisco Cherry Blossom Festival with my family, and visiting Uwajimaya to get ingredients for Oshōgatsu. I feel very fortunate to have grown up in an area where there was a thriving Japanese American scene in which I could explore this part of my identity.”

Dr. Shimizu (born 1928, Prince Rupert, BC) is pleased with the job that the University of Victoria and curators did to present his work: “The show is beautifully mounted and impressive,” he says.

These days when travelling, Dr. Shimizu still does some watercolours. Lately, he’s been staying closer to home in Victoria, BC with wife, Joan. Son Greg (Twilla) lives in Edmonton.

Dr. Shimizu says that the 27 paintings (oil on canvas) were painted between 1999 and 2002 and depict life between 1942 and 1946 as a teenager. They tell the story of Japanese Canadians who lived and worked there, who succeeded “despite the efforts of ‘bigots’ especially in BC who hated us because we tried so hard.”

The show is a relaunch of the 2012 one at UVic where the theft of the painting, Vegetable Gardens, promptly closed the show.

Samantha explains: “It’s a piece that displays the shiplap houses in the camp interspersed with neat rows of planter boxes. Henry describes that by the second year of internment, almost every house in the camp had its own vegetable garden. It is now 10 years since the painting was stolen, and we still do not know the motivations behind the theft of this particular painting, or where the painting is today. The loss of this painting resulted in the immediate closure of the exhibition. Not only was this a dear loss for the JC community, but it also contributed to the erasure of this important part of history.”

In 2020, social activist, researcher, and retired UVic professor, John Price, urged the university to remount the 2012 exhibition as an act of reconciliation and a statement against rising racism.

Henry’s Story….

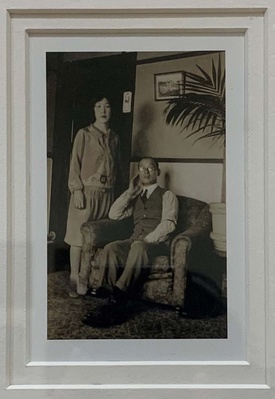

Dr. Shimizu’s story begins in 1915 when his father Shotaro (Tom) Shimizu and Y. (George) Nishikaze were partners in the Dominion Hotel and Restaurant, on Main Street in Prince Rupert, B.C. His father’s first wife died when she returned to Japan for her second child during the Spanish Flu pandemic. Her son, Andy, stayed in Japan and lived with the grandparents.

“My father returned to manage the Dominion Hotel. George Nishikaze continued there as the cook, an outstandingly fine cook for all kinds of Western food. The Dominion Cafe was very popular in Prince Rupert and the business prospered even during the Depression of the 1930s. My father remarried (Kimiko) in 1926 in Japan and I was born in 1928 in Prince Rupert. Our family continued to expand to include two girls and another boy. Then, in 1936, Papa’s first son returned to Prince Rupert to complete the family. With the beginning of WWll in 1939, Prince Rupert became a ship building centre that was as busy as a bee hive.”

Tom and George prospered until December 7th, 1941. On March 23, 1942 the family was removed by train first to Vancouver (Hastings Park):

“The train ride was about 24 to 36 hours; we arrived into Hastings Park in Vancouver in the late afternoon. Hastings Park was surrounded by a chain-link, 8-foot-high fence; there were several gates and there was train access with tracks for Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) cargo. It was an ideal manning depot and therefore used to round up all the Japanese people who lived outside greater Vancouver.” Meanwhile, his father and older brother, Shoji, had been sent earlier to work camps in the interior of BC. Six months later in September, the family was moved to the New Denver Internment camp.

“New Denver was a new experience for our two families. We were housed together in one of the largest houses. For the first time we had Japanese neighbours. Within a short time we were making friends with schoolmates and learning new skills like hockey and baseball.”

Recalling the topography of the New Denver internment camp, Dr. Shimizu says that:

“[it] was somehow constructed on a delta of land which was owned by an Italian farmer called ‘Watson.’ The whole area was farmland and there was an orchard. When they built the shiplap houses, they were placed to follow the contour of the delta land and to save as many of the fruit trees as possible. In fact, all of the large cottonwood and elm trees were saved as well as the evergreens. There were shoreline houses and view lots looking across Lake Slocan and the glaciers on the mountains. There was a bay and a large lot on the southern border of the camp where a TB sanitorium/hospital was being built with offices and nurses’ houses.

“As you approached the internment camp from the south highway hill, the area looked like a summer resort. Why didn’t they build the orderly rectangular ‘concentration’ shape like Tashme is a mystery. The presence of trees also changed the ambience. People were friendly, there were no ‘snoopers’ in the evening like in Tashme.

“Eventually, all of the people called the internment camp the Orchard. The ambience of the orchard was calming. In the summer, it was mellow in the evening. The climate was ideal for gardening and after the first year everyone had a vegetable garden, many had more than one. After the first year, New Denver became the site for the yearly summer school for new teachers, as the ‘ghost town’ teachers who taught in the internment camps would come to ‘brush up’ their skills as well as enjoy the pleasant surroundings. When we had our get together in 1999 at my sister’s house in Toronto, there were about a dozen people there each of whom had lived in the Orchard. His siblings are sisters Grace (1929), Eva (1935), and brother Kaien (1937).

“My sister said the Orchard and surrounding area felt safe. She remembered walking with a friend and taking one of the girls back to her home which was up a hill about a mile at midnight after a teen town dance at Bosun Hall. She remembered it was dark but they were not concerned. During the winter there was lots of snow but the weather was rarely below 0 temperature except during that first winter in 1942 when there were several weeks when it was below 0 and the shiplap shrunk and the cold entered the bedrooms.”

“The next year we split cedar shakes and covered the walls and some of the roofs. We never had that problem again. The New Denver internment camp was the last to be built and it never looked or felt like a ‘prison’. The chief builders, the Matsumotos, were a family of Japanese boat builders who had built the best Japanese fishing boats in Prince Rupert and had their shop in ‘Cow Bay.’

“As teenagers we spent most of our time at school or in the playground playing baseball and hiking in the woods as there were no fences. All kids had chores. As we grew older, in the summer there were forest fire workers or fruit pickers in the Okanagan. The young women were organizers of the teen dances, Sadie Hawkins, Valentine, Halloween, Christmas, and New Year’s.

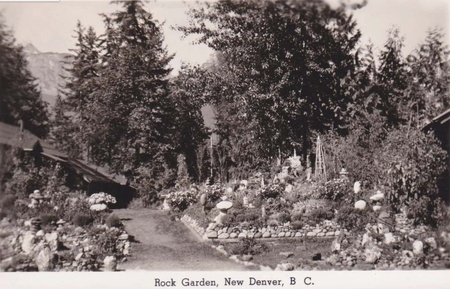

“There was a revival of Japanese culture—girls had odori and danced to records that they’d saved, wearing their heirloom kimonos. Despite the life savings that the elders lost, they enjoyed a social revival of ofuro (baths) and gossip. Every house had a vegetable garden, except the Shimizu/Nishikaze rock garden which kept getting larger and larger until it abutted the Watsons’ barn. One could even buy a postcard of the unique Japanese Garden in New Denver. It was an actual rock garden. Yes, George was Japanese but a cook, not a gardener.”

© 2022 Norm Masaji Ibuki