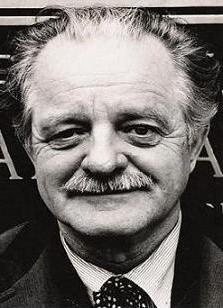

Kenneth Rexroth (1905-1982) is, in many ways, California’s poet. Although born in Indiana and having spent most of his young adult years in Chicago, Rexroth left for California at age 22, and spent the remainder of his life there. During those subsequent fifty-five years, Rexroth embarked on an ambitious career as a poet, painter, and political activist, living the first half of his California years in San Francisco and his later years in Santa Barbara, where he was a professor of English at University of California, Santa Barbara.

As poet Donald Hall described Rexroth in a 1980 overview of the poet’s career for the New York Times, Rexroth was both “the most erotic of the modern American poets, and one of the most political.” Already a “Wobbly,” or member of the International Workers of the World, from his early days in Chicago, Rexroth aligned himself with Marxists of the John Reed club once he arrived in San Francisco. The trial and execution of Sacco and Vanzetti in 1927 for Rexroth was, according to Hall, the “great event of his young life,” one that inspired him to pen the poem “Climbing Milestone Mountain.” Throughout his career, Rexroth laced his anarchist political views and his philosophies on the human condition throughout his poems.

Although San Francisco possessed a distinct culture as a crossroads of the Pacific by the time that Rexroth arrived in 1927, his literary sketches of San Francisco would represent one of the many marks he would leave upon the city. Beginning in 1936, Rexroth was hired by the Federal Writers Project, and served as a contributor to the famed WPA guides on San Francisco and California. These guides, created as part of its New Deal initiative to hire unemployed workers and document the culture of American cities, allowed Rexroth and other writers to define the culture of San Francisco.

Unlike most white residents of the West Coast, though, Rexroth was troubled by the racism he saw there. Perhaps no event shook Rexroth morally as much as the wartime removal and incarceration of his Japanese American neighbors during World War II. His actions to support Japanese Americans in camp are deeds that should be remembered.

Already from the outset of war, Rexroth anticipated a rise of anti-Japanese sentiment of California. In a letter dated December 28, 1941 that Rexroth wrote to his friend, poet, and publisher James Laughlin, he discussed the state of opinion in California following U.S. entry to the war. Rexroth attested to the racial hysteria prevalent in California, stating “people seem to take an invasion attempt for granted, and expect our yellow brothers to wage a war of literal extermination against California.”

In describing to Laughlin the state of affairs on the West Coast, Rexroth bluntly stated his outrage over West Coast racism: “the prejudice against Orientals in California has always sickened me. Maybe the constituents of Senator [Hiram] Johnson realize they are being called to a terrible accounting for the Oriental Exclusion Act.”

Following the outbreak of war, Rexroth joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a pacifist religious group noted for social activism. As historians Greg Robinson and Peter Eisenstadt have noted, the San Francisco chapter of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, led by African American theologian Howard Thurman, would play an important role in supporting Japanese Americans in the latter stages of the war.

After the announcement of forced removal by the War Department in March 1942, Rexroth stepped into action. He and his wife, Marie Kass Rexroth, began collecting books to help confined Japanese Americans to organize a library. He described the process to his friend, artist, and poet Weldon Kees:

“We are trying to collect all the Japanese books we can to establish a library service from the camps [i.e. Assembly Centers] and later the relocation projects. Miss Gillis of the State Library will handle distribution…the county librarians in the counties where there are camps and projects will help in whatever setup is necessary and will act as physical contacts with the Japanese librarians within.”

The system that Rexroth helped to organize would continue to provide books to inmates for the duration of the incarceration, with each camp possessing a small library of books for both leisure reading and for students enrolled in the camp schools.

Following the forced removal of Japanese Americans, Kenneth and Marie Rexroth made regular visits to the nearby Tanforan Assembly Center, starting in April 1942. Constructed on the grounds of the Tanforan Racetrack near San Bruno, the Army’s so-called “assembly center” held thousands of Japanese Americans, mostly from the Bay Area, who were confined in crude tarpaper barracks and horse stalls.

During each visit to Tanforan, the Rexroths delivered supplies to Japanese Americans there. Kenneth Rexroth helped organize the library and assisted with art projects in the camp. Marie Rexroth, a nurse, donated her vacation hours from work to volunteer as a public health nurse at the camp. Although Japanese American health care workers did staff the camp hospitals, the need for additional doctors and nurses remained constant.

Rexroth was particularly sensitive to the problems facing the Issei, or first-generation Japanese immigrants. As part of his library project, Rexroth requested reading materials in Japanese that would provide Issei readers with texts that they could connect with: “the big problem is to find and save and organize the distribution of the books in the Japanese language. Otherwise the Issei will have nothing to read for the duration, some of them.”

At a time when law enforcement officials suspected Japanese-language materials of any kind as ‘treasonous’ and led Japanese American families to destroy any possessions connected to Japan, Rexroth’s desire to collect Japanese language text is remarkable. Sadly, the Army barred possession of Japanese-language books by the inmates and army staff at most of the assembly centers, including Tanforan, purged Japanese-language books from the libraries.

According to the Densho Encyclopedia, only the Sacramento Assembly Center housed a significant collection of Japanese-language texts. While over time the more permanent War Relocation Authority camps slowly began allowing Japanese books, problems of supply and public relations kept them largely unavailable.

The experience of the Japanese Americans horrified Rexroth. After visiting Tanforan in Spring 1942, he confided his negative reaction to Weldon Kees: “We took another trip to Tanforan Concentration Camp – just as appalling as ever, and twice as hard to get into. Honest to God Weldon – you just don’t know how horrible it is.” It is impressive to note here that in letters to various friends like Kees, Rexroth consistently described Tanforan as a “concentration camp,” rather than refer to it by the Army’s euphemistic title of “assembly center.”

At the same time, Rexroth befriended a number of Japanese Americans, and provided moral support for resistance. Rexroth instructed Kees, then living in Denver, to get in touch with several Japanese Americans who had “voluntarily” left the West Coast. One such individual was James Omura, a noted journalist and activist who had vocally protested the incarceration policy in Congressional hearings, and then had moved to Denver to avoid camp. Rexroth described Omura as “as a good man” and a “solemn oaf,” and noted “he is considered a Trotskyiste-Fascist or something similar to Isamu Noguchi and pals.”

Rexroth also assisted Japanese American college students enroll in the Midwest Art Academy of Chicago as a means of getting out of camp. According to Rexroth biographer Linda Hamalian, Rexroth came up with the idea of acquiring educational passes for students hoping to leave the exclusion zone after one student, Hazel Takeshita, told him she wanted to learn how to crochet, in order to design dresses for a living. Rexroth asked Army officials about enrolling students in outside schools. Already busied with creating the camps, they hastily agreed to Rexroth’s idea but left it to him to execute. In the end, Kenneth and Marie Rexroth helped dozens of students to avoid years of confinement, and frequently saw students off at the train station, many of them leaving their possessions with Rexroth as they departed.

One individual who particularly benefited from Rexroth’s help was activist Lincoln Seiichi Kanai. Originally from Hawaii, Kanai had served as executive secretary of the Buchanan Street YMCA in San Francisco starting in the prewar years. After the announcement of Executive Order 9066, Kanai worked tirelessly to persuade military leaders to avoid sending U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry to the camps, especially those individuals with health problems.

During this time, Kanai developed a close relationship with the Rexroths, frequenting their house on 124 Moreland Street in San Francisco. Kanai intentionally violated the Army’s exclusion order by leaving San Francisco in May 1942 in over to take a tour of the Midwest and East Coast colleges.

Upon his departure, Kanai left possessions and letters with Kenneth. As Kanai embarked on his tour, Kenneth served as a go-between to permit friends in camp to keep in touch with Kanai. Rexroth wrote to Weldon Kees to instruct him to take in Kanai if he visited, and described the Nisei to his friend as “a pearl without price. The real saint of the evacuation.”

On July 11, 1942, when Kanai was in Wisconsin on his tour, he was arrested by the FBI. Tried before a federal judge, Lincoln Kanai argued unsuccessfully that the exclusion order was unconstitutional – a similar argument as that which Fred Korematsu would raise before the Supreme Court two years later. Following trial on August 27 Lincoln Kanai was sentenced to a six-month prison sentence at Fort Lewis, Washington.

In October 1942, the Army closed the Tanforan Assembly Center and transported the Japanese Americans incarcerated there to one of ten long-term concentration camps operated by the civilian agency known as the War Relocation Authority. Rexroth chose not to move east with Japanese Americans, citing his own projects in San Francisco and his desire to not “become morally involved with the procedure.”

Undoubtedly, the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans left a deep impression on Kenneth Rexroth. In later years, Rexroth learned Japanese to begin translating poems, and promoted Japanese poetry in his 1955 translation book One Hundred Poems From the Japanese.

While Rexroth is part of a long tradition of Western poets influenced by Japanese poetry and aesthetics – he saw productions of Ezra Pound’s translations of Noh plays during his youth in Chicago – his support of Japanese Americans and translation work distinguished him from other poets. Perhaps only John Gould Fletcher, the Southern Imagist poet who studied haiku and mentored Japanese American haiku expert Kenneth Yasuda, shared a similar rapport with Japanese Americans. Both in his own works and in his translations of Japanese poetry, readers can sense Rexroth’s deep respect for Japanese culture, one that many Beat writers of the time arguably treated with fleeting interest.

Although Kenneth Rexroth was not the sole supporter of Japanese Americans among West Coast whites, his willingness to devote countless days to helping the community amidst persecution attests to his courage and strong sense of morality.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen