In March 1942, the U.S. military decreed that all persons of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast must relocate eastward. About 9,000 voluntarily moved,1 and the War Relocation Authority (WRA) forcibly moved 120,000 people—about 80,000 being U.S. citizens and the remainder being immigrants—from their West Coast homes to remote relocation centers.2 The Relocation caused the closing of Japanese-speaking Christian churches and Buddhist temples and severely disrupted the religious lives of the relocated. Although some aspects of the history of the Relocation have been well covered, little has been documented about how the internees reconstituted their religious communities. This article helps to fill this historical gap by exploring stories of selected Buddhist altars and poems created by Japanese immigrants, particularly at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center, between 1942 and 1945.

Immigration and the Establishment of Japanese-Speaking Religions and Traditions

Japanese immigrants began to arrive in the West Coast around the end of the 19th century—about 50 years prior to 1942—and stopped arriving after 1924, due to U.S. exclusionary laws.3 By law, these immigrants could never become citizens. Consequently, at the time of Relocation, the older U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry were at least 25 to 30 years old, born in the United States, and able to speak and read both Japanese and English. These adult citizens were the leaders of official Relocation-center business, because those positions required citizenship. The official language of the Centers was English. However, the universally spoken language in the centers was Japanese, not English, because most of those who were relocated were immigrants and children (teenage and younger), all of whom spoke Japanese.4 Among the immigrants, the written Japanese language was in kanji, hiragana, and katakana. Even today, it is difficult to translate between written Japanese and English. Many immigrants continued using the Japanese calendar, even though they had lived in the United States for years and had daily contacts outside of the Japanese community. Dates were in reference to the Tokugawa Shogunate, and the later Meiji, Taisho, and Showa eras—eras after Japan’s self-imposed isolation, eras when the Western world discovered Hiroshige, Hokusai, and Japanese ceramics.

One may wonder why the words Issei and Nisei have not been used in the above discussion. In common American usage, Issei refers to a Japanese immigrant, and Nisei refers to a U.S.-born child of an immigrant. However, the kanji for Issei really means “first generation,”5 and Nisei means “second generation.” Therefore, the common American usage misrepresents the fact that the Japanese immigrant family often had multiple generations of immigrants (not just a single, “first” generation). This common usage also hides the fact that U.S.-born children were automatically U.S. citizens but Japanese immigrants were forbidden to become U.S. citizens until 1952, when citizenship was permitted and immigration quotas were established. In the stories being told here, U.S. citizenship—not generational differences—is the unique separating factor during Relocation for people of Japanese ancestry and this point would be lost by using Issei and Nisei.

Returning to the stories being told, it probably is not wise to give a single reason for Japanese immigration to the United States. Many immigrants left Japan permanently, but they did not leave behind their connections with Japan and they took their religions and traditions with them to the United States. Among the many religions in Japan that immigrants brought to the United States were Christianity, which existed in Japan long before immigrants left for the United States,6 several sects of Buddhism (e.g., Higashi Honganji, Nishi Honganji, Jodo Shu, Nichiren, Shingon, and Zen), and Shinto. The early immigrant communities would often ask religious centers in Japan to send ministers and priests to tend to their needs. Even after 1924, these Japanese ministers and priests were able to come to the United States because they were not covered by the 1924 exclusionary laws. As for traditions, the immigrants continued to recognize household deities and spirits, often presenting food offerings to them.7 Special days, such as Obon, Hana Matsuri, Boys Day, and Girls Day, were celebrated. Mochi-tsuki and other New Year’s Day traditions were especially preserved.

Religious Life During Relocation: Filling Vacuums and Voids

By 1941, many Japanese-language schools, community and entertainment centers, and Japanese-speaking Christian churches and Buddhist temples were established in the West Coast states. When the Relocation was proclaimed in 1942, these meeting places were all closed. However, the practice of Japanese religions was not prohibited during Relocation.8 The WRA permitted the practices of Japanese-speaking Christianity and Buddhism to continue, as witnessed by newspaper articles from the Relocation centers. (The newspapers did not contain articles on Shinto events; possibly none occurred.) In some Relocation centers, more than one Buddhist church was formed; for example, five were established in the Heart Mountain Center.

Altars are central to many sects of Buddhism, and the Relocation created an altar vacuum. For these sects, their newly formed churches lacked altars. Also, many Buddhists of these sects had left their home altars behind. In at least a few of the centers, internees filled the vacuum by making altars for personal home use. At the Heart Mountain Relocation Center an unusual collection of artisans built small altars for personal home use and larger ones for church use.

Large altars were not of central importance to the Zen Buddhists. Unlike the organized Buddhist churches in the Heart Mountain Relocation Center, which required large halls, the Zen Buddhists used small meeting places for meditating and performing their daily rituals. The renowned Zen priest Nyogen Senzaki established such a meeting place in the Heart Mountain Relocation Center. Additionally, he composed, for Zen Buddhists and others, poems and religious writings for special holidays. After abruptly leaving behind their established West Coast lives and arriving at the Heart Mountain Center, the internees found themselves in a Relocation-created void to endure a harsh, disorganized life of a Relocation Center. Using poetry, Senzaki reminded the internees of how the void in their new life could be filled by events such as the making of paper flowers or the rising of a winter morning sun. Perhaps this filling of the Relocation-created void was not as tangibly dramatic as the filling of the altar vacuum. Nonetheless its effect is subtly seen in Senzaki’s poems and writings, and in stories surrounding them.

In the following sections, stories of the many Buddhist altars built in the Heart Mountain Center, large and small, will be told. Stories involving Zen life and poetry at Heart Mountain will also be told.

The Large Altars of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center

Members of two major Nishi Honganji churches, one in Los Angeles and the other in San Jose, were relocated to Heart Mountain Relocation Center. Among those relocated from San Jose were several people associated with the Nishiura Construction Company. This company was established in the mid-1910s, and in 1937 it built the San Jose Buddhist Temple (Figure SJ), which was modeled after the famous Nishi Honganji Temple in Kyoto, Japan (see SJBCB). People connected to the Nishiura Construction Company who were sent to Heart Mountain included the brothers Shinzaburo and Gentaro Nishiura, who operated the company, as well as three of their employees: the skilled craftsmen Fumiji Harazawa, Choji Sakaguchi, and Suetsuna Okashima, all immigrants from Japan.9 The Nishiura brothers and this group of craftsmen, together with other talented helpers, built four large altars used in makeshift Buddhist churches during Relocation at the Heart Mountain Center: the Horiuchi Obutsudan, the Kubose Shumidan, the Aso Obutsudan, and the Shibata Obutsudan.

The Horiuchi Obutsudan

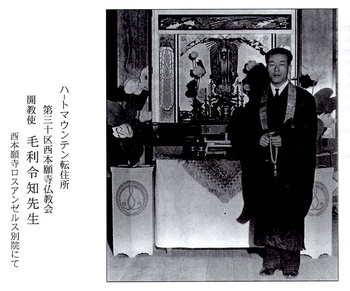

The Heart Mountain Center opened on August 12, 1942, and soon after, in October 1942, a Nishi Honganji Buddhist church was opened in Block 30, becoming the first Buddhist church to be opened in the center. The members of the Block-30 Church were from Los Angeles, San Jose, and Yakima, Washington. Its altar, which will be called the Horiuchi Obutsudan, was also the first to be built. (In kanji, obutsudan is the honorific form of the word butsudan.) The obutsudan was dedicated on April 18, 1943. The dedication photo (Figure 1) shows Reverend Reichi Mohri standing in front of the obutsudan. Note that the writing on the photo is in kanji and is read from top-to-bottom and right-to-left, in the usual Japanese way.

Information about the Horiuchi Obutsudan has been taken from Masuyama [pp 11, 15]. Figure 1 shows panels to the left and right of the obutsudan. They are actually panels of a four-panel folding door that covers the front of the box-like altar. The box is 5 feet wide, 4 feet tall and 30 inches deep. The cabinetry of the obutsudan was designed by Shinzaburo and Gentaro Nishiura. There is a photo in the Masuyama reference of Shinzaburo Nishiura building the altar in the Heart Mountain Center Cabinet Shop. Yutaka Shinohara, a U.S. citizen and a member of the Block-30 Church, designed some interior features—the top panel and the two side panels of elliptical hanging wisteria, which is called sagari fuji mon. In Figure 1, one of the side panels is behind Reverend Mohri. Koichi Konishi, a U.S. citizen, of the Heart Mountain Cabinet Shop carved the three panels. The exterior of the obutsudan is painted glossy black, except for the four panels of the door, which are trimmed in glossy black. Togoro Iguchi applied the interior gold paint. Enshrined in the altar is a statue of Amida Buddha that was brought from the Yakima Buddhist Church to Heart Mountain by Yonekichi Hashimoto.10

By the end of 1944, the March 1942 military decree on the West Coast exclusion of Japanese Americans had been rescinded, a day before the Supreme Court ruled that loyal U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry cannot be detained against their will.11 All Relocation centers were scheduled to be closed by the end of 1945. With the Heart Mountain Center closing in November 1945, the Block-30 Buddhist Church’s obutsudan was no longer needed. When Katsujiro Horiuchi, treasurer for the Block-30 Church, returned to Los Angeles, he took the obutsudan for his personal home use. The Amida Buddha statue found its way back to the Yakima Buddhist Church. During the years after it was moved to Los Angeles, the obutsudan was slightly damaged. In the early 1990s Horiuchi donated his obutsudan to the Japanese American National Museum.12

Notes: (*The references occur at the end of the fourth part.)

- This number is from WRA, page 3.

- For these numbers see NJAHS, page 28, and GR, page 41.

- For a brief informal survey of exclusionary laws, see NJAHS.

- For further breakdown of the numbers see NJAHS, page 26.

- Issei is the romanji version of the Japanese word, and it consists of two kanji characters, namely, the characters corresponding to is and sei. The kanji character for is means “first”; and there is a kanji character for sei meaning “generation,” although there are other characters for sei. (See SH, page 1648, where over 80 kanji characters for sei are listed with various meanings.) In the context of this article, only “generation” is appropriate. Common American usage has turned the meaning of Issei into “Japanese American immigrant,” which makes its use ambiguous in some contexts.

- See Kashihara, for instance.

- For an interesting book on spirits and traditions see Hearn’s Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan.

- See Mackey, pages 67-68, for partial information.

- The named craftsmen were members of the Heart Mountain Carpenters Club [HMCC]. The club had over 400 members. A small digression will be made here concerning the need for so many carpenters. Heart Mountain Relocation Center was built on empty land in Wyoming. The center opened in August 1942, and it was still being built when occupation began. The population went from zero to over 10,000 in a very short period of time. Families were placed in uninsulated barrack rooms with one overhead light and a potbellied coal-burning stove in each room, and were provided with just metal cots, mattresses, and blankets—even though a frigid winter would soon be arriving. No privacy was afforded parents and adult children; no furniture was to be found on arrival. Schools and a hospital had to be built and furnished; vital community centers had to be furnished. The carpentry needs were therefore great. The same was true with the feeding of the people of the newly created Center. For these aspects and many others of life in Heart Mountain Relocation Center, see Sakauye.

- See page 328 of BCA for the source of this statement. There is a conflicting statement on page 13 of Masuyama, which uses a secondary source.

- See NJAHS, page 64.

- See Masuyama, page 15.

© 2015 Togo Nishiura