In 1990, two years before the Japanese American National Museum opened to the public, curator Brian Niiya looked through a shabby old trunk in Albertson, New York. An elderly Japanese American gentleman and his wife had recently died. Neighbor and family friend Gloria Massimo had preserved the trunk full of letters, papers, class notes, printed materials about landscaping, and thousands of photographs. Urged by Museum charter member Lily Kiyasu, who had met and interviewed Shogo Myaida and his wife Grace, Ms. Massimo contacted the Museum’s collection department and eventually donated the trunk full of history to us.

Collection manager Grace Murakami and archivist and National Resource Center manager Debbie Henderson, tell how this large collection became accessible to researchers and scholars. Student intern Gary Colminar spent the summer of 1997 sorting through, inventorying, and cataloguing every item in the collection. A fascinating story emerged.

Shogo Maeda was already a well educated landscape architect and world traveler by the time he landed in New York in 1922. He was 25 years old, the son of a wealthy Japanese family—his father was a member of Parliament—and for the first time in his life was faced with making a living. He decided to stay in the United States since he was absorbed by the new architecture he saw all around him. At first he lived in a Japanese church rooming house with 15 or 20 other Japanese, whom he “didn’t like at all,” he remembered in a 1988 oral history interview. He considered himself to be very different from the others, who were sons of Japanese farmers and worked as domestic servants. “I got out as soon as I could get out,” he remembered, and indeed, for the rest of his life he seldom associated with other Japanese or Japanese Americans. He corresponded only occasionally with his family and never again visited Japan.

Myaida (who changed the spelling of his name so that Americans would be more likely to pronounce it correctly) considered that American culture had changed him to the point that he would not be accepted in Japan—“Japanese people were afraid of me because I come straight out…anything I wanted to say,” he recalled. “Japanese is different, hesitating and bowing and even talk doesn’t come…straight out.”

His mother, a writer and poet, also urged him to stay in the United States. He remembered her telling him that, as long as he was interested in what he was doing, he should stay to learn from American young people “to work and make living themselves, not like Japanese kids (who) just live on family wealth.”

Myaida began his career working in an architectural firm in New York and soon began to build a network of influential people who were able to help him to find bigger and better jobs. A friend at the New York Botanical Garden helped him to get a job rehabilitating the grounds of a girls college in Georgia. Later, he went to Florida and worked for several well known architects in Palm Beach, where he first met Marjorie Merriweather Post, the cereal heiress, whose magnificent homes in Palm Beach and Washington D.C. were legendary. Myaida went back to Long Island in 1926 where he worked for a large landscape contractor, creating and improving many private gardens.

During the Great Depression he scraped by, gardening and, in the winter, selling manure for mulch and sharing rent and food with fellow workers. “For many days,” he remembered, “we had rice and a big iron pot full of split pea soup on a big old coal stove in the kitchen.”

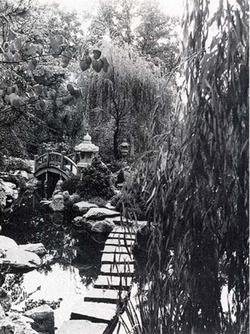

In 1938, recovered from the depression years, he supervised the landscape design for the New York World’s Fair Japanese Garden and was in charge of its maintenance during the run of the fair. He married his young American secretary and bookkeeper in 1941, “and shortly after Japanese started to fight with America. We had quite a time. The FBI came over and check all my house and everything I had and they said that as long as I stayed in Albertson (New York) I do not need to go to Ellis Island.” He found jobs working in greenhouses during the war, and “then when the war was over, and get freer so I started designing gardens all around again.”

In 1952, Myaida read in a newspaper that Japanese-born people could become American citizens, and he applied for and received American citizenship. Shortly afterward Mrs. Post’s landscape architect contacted him about doing a Japanese garden at Hillwood, Mrs. Post’s 25 acre estate in Washington D.C. Myaida modestly remembered that the garden was “quite good,” and then added, “supposed to be one of the best on the East Coast.” Today the estate is a museum and garden, open to the public, and Myaida’s beautiful garden is in the process of restoration.

Myaida retired in 1972, and in 1988 described his “happy, harmonious marriage with an American girl” as one of his life’s achievements. “We went through hardships, but we had happy days all through the last 47 years.” Grace Myaida died in March, 1989. Shogo Joseph Myaida followed her a few months later in May, 1989.

*Much of information in this article, and all of the direct quotes, are from the transcript of an interview conducted with Shogo Myaida on July 10, 1988 by Dorothy Rony, New York Chinatown History Project; Lorie Kitazano, Queens college, Asian History Studies; and Lily Y. Kiyasu, Garden City, New York.

*This article was originally published in the Japanese American National Museum Quarterly magazine, Summer 1998.

© 1998 Japanese American National Musem