Greenwood, British Columbia, in Canada became the first internment center when Nikkei people were uprooted and “relocated” from the coast of B.C. On December 7, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, and shortly after Canada declared war on Japan when Hong Kong, a British Commonwealth, fell to the Japanese army. This started a chain reaction of government decisions to remove the Japanese Canadians from the coast. With the War Measures Act enforced, Japanese Canadians were helpless. Maybe that’s where the term “shikata ga nai” came to be. It can’t be helped. Those who protested were sent to POW camps in Petawawa or Angler in the province of Ontario. In order to understand the “why” and “how” Greenwood was chosen, one needs to go back to the early 1900s.

Powell Street was coined “Japantown” by the mainstream Vancouver population. Hastings Sawmill hired mostly Japanese immigrants to do manual labour as early as the late 1800s. As a result, a Japanese community sprang up when workers needed boarding houses and places to eat. Hotels, shops, restaurants, stores, and bath houses were established to cater to the needs of the labourers. Japantown’s population increased considerably when single men called for wives over from Japan to start a family. Powell Street was booming. Japanese Language School was established. They even had a shibai (drama) contest each year, and the Shiga-ken actors usually took first prize with their lively rendition of songs and dances.

According to Jacqueline Gresko’s research article, Kathleen O’Melia was an Anglican missionary in East Vancouver in 1902. By 1912, Kathleen converted to Catholicism when she had a calling to help the Japanese on Powell Street. Kathleen was called O’Melia-san by the Japanese. In 1926, she was ordained Sister Mary Stella at the age of 57.

Sr. Mary Stella started the Japanese Catholic Mission on Dunlevy and Cordova Street. The Sisters opened up a kindergarten class and a daycare center for the Japanese children. Those parents who were called away from Vancouver to do contract work left the children with the Sisters. By 1930, there was a small group of converts. Father Benedict Quigley was a Friar back then who learned the Wakayama dialect to speak to his parishioners.

In 1931, the Franciscan Sisters and Friars of the Atonement from Graymoor, New York, opened another Japanese Catholic Mission in Steveston. There was a large Japanese community there with mainly families employed in the fishing industry. Sr. Antoinette and Sr. Mary Stella knocked on the doors of the cannery row houses where the Japanese families lived. In a short time, they had over 200 converts and four men training in priesthood. Unfortunately, Sr. Mary Stella died in 1939. She was unable to see her dream become a reality, but others continued on to help achieve her goal to establish Japanese Canadian missions. Fr. Peter Baptist Katsuno became the first Japanese Canadian who was ordained in the Franciscan Order. By 1941, the overall “Japanese” population had risen to 2,000 out of 2,500 in Steveston.

World War II changed the course of history for the Japanese Canadians. Hastings Park Exhibition Ground was the holding center for all the Japanese Canadians who lived on Vancouver Island and up the coast of Prince Rupert. Those who lived in Steveston and Vancouver were able to live in their homes until such time they were called to move out.

This is where the Franciscan Sisters and Friars played a pivotal role in the internment process. Many of the parishioners asked the Sisters to find them a safe place. Fr. Benedict Quigley went above and beyond the call of duty to make this possible. He drove all the way to Nelson, B.C., in the interior to see if he could find a town that would accept the Japanese Canadians.

Bishop Martin Johnson suggested that Greenwood, slowly becoming a ghost town, might accept them. Father Benedict drove to Greenwood to meet with then mayor W.E. McArthur Sr. There were a few issues that needed to be resolved. First, the mayor told Fr. Benedict that the town folks were concerned with safety if he accepted the “Japanese”. Father explained to the mayor that it was the complete opposite. The Nikkei people were the ones afraid because they had no place to go! This was told to me by Mitsi (Sasaki) Fugeta.

Eventually, the mayor agreed to have a town meeting to cast a vote. According to Molly (Madokoro) Fukui, mayor McArthur tried to convince the local folks at the meeting that Greenwood needed people, and that the Japanese from the coast had nowhere to go. After several meetings, the town folks agreed to accept the incarcerated Japanese Canadians only if the Franciscan Sisters and Friars would guarantee the safety of the local people and that they would take full responsibility. In the end, the vote was almost unanimous. Only two still voted no.

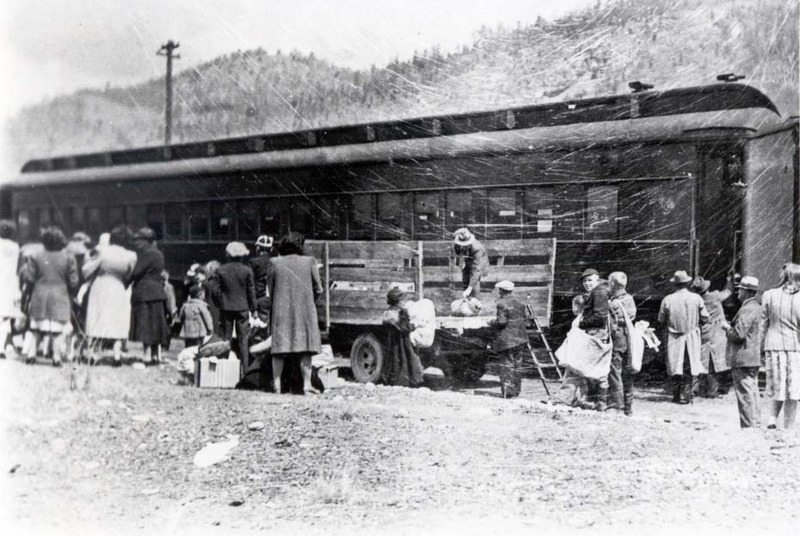

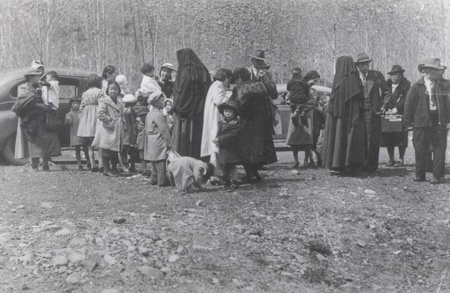

Sr. Jerome Kelliher and Sr. Eugenia Koppas took an 18-hour train ride to Greenwood a day ahead to make sure there were familiar faces when the first trainload arrived. On April 26, 1942, the train reached Greenwood with mostly elderly men, women, and children. Young men were sent to road camps.

Mayor McArthur had his welcoming party to greet the first Japanese Canadians to step off the train. The Sisters were there to greet the Catholic parishioners. A truck was waiting to load the suitcases and some of the people to their accommodations. There were many vacant hotels available when Greenwood was once a booming smelter processing city of 3,000. In 1918, the copper price dropped so low that the smelter ceased operation. The population dropped drastically to under 200. Nearly 1,200 Nikkei filled the rooms of the old hotels and houses.

Once these well-dressed city people from the coast proved themselves to be honest, hard-working citizens, the anxiety of the local folks waned. There were several sawmills established to take advantage of the great labour force when the men came back from the road camps. Greenwood once again boomed.

When war ended in 1945, the government was adamant that they did not wish the Japanese Canadians to return to the coast. Therefore, the ultimatum of the government was, “Go East of the Rockies or Repatriate to Japan.” Greenwood Board of Trade protested this unfair legislation. When other communities agreed with the government’s sanction, Greenwood did not. Thus, the Nikkei families were not pressured to accept the “rock and a hard place” choice given to them. Finally in 1949, the government under criticism allowed the Japanese Canadians to return to the coast and have all the freedoms of a Canadian citizen.

The Nikkei residents must give thanks to the people of Greenwood for the support that they have demonstrated to keep the “adopted” locals in the community. The Nikkei population was still around 700 after 1949. The total population was close to a thousand in the ’50s. When other internment camps closed down, many families had to choose their destination. Most of them went to Ontario and Quebec. Some went to the prairies. Nearly 4,000 chose Japan.

That is how and why Greenwood became the first internment center. The make-shift camps in Lemon Creek, Popoff, Bay Farm, and Rosebery in the Slocan Valley and the self-supporting camp of Lillooet in the Cariboo were dismantled and have disappeared. They are just a distant memory with only a farmers’ field as evidence. Only New Denver had a small Nikkei community after the war. The Nikkei Internment Memorial Museum is located in this town.

In Kaslo, the last remaining Nisei passed away this year. Former teacher, Aya Higashi, was very well-respected and her name is honoured at St. Andrew’s United Church and at the Langham Hotel Museum. A handful of Nikkei residents remained in New Denver. However, Greenwood still has about 30 Nikkei who planted their roots and have never left. Of course, many have died in Greenwood or have moved away to be close to their sons and daughters.

Greenwood Museum has a Nikkei history section and a Nikkei Legacy Park being upgraded. The Franciscan Order of the Atonement played a huge role in bringing the Japanese Canadians to Greenwood. The United Church played a small role as well. It is the “what if” question. How different the Nikkei history could have turned out if it wasn’t for Mayor McArthur’s decision to accept the Japanese Canadians to Greenwood? We could very well have been picking sugar beets in the prairies or shipped off to Japan, a country where most Nisei had never visited. Greenwood Nikkei were indeed very fortunate.

© 2016 Chuck Tasaka