On Wednesday, May 24, 2017, a meeting was held in Ubatuba to discuss the institution in the city's official calendar of a day in honor of Japanese immigrants in Brazil. The meeting took place in a room at the City Council and began at around ten-thirty in the morning.

Present were Mrs. Kazuco Sakiara Miyasaka, her husband Shiro Miyasaka and their daughter Melisa Miyasaka Sakamoto, as well as two members of the Associação Filhos da Ilha, Iara Ribeiro Dias and José Walther Cardoso, councilor Osmar Dias de Souza (PSD) and the legal attorney from the Chamber of Ubatuba, Isac Joaquim Mariano.

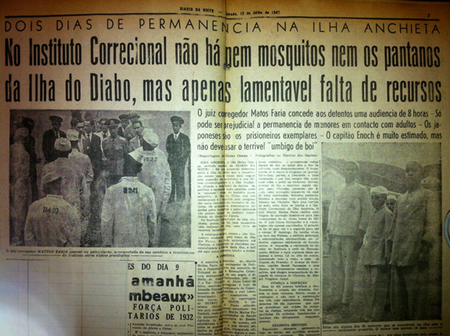

On the occasion, Melisa Sakamoto handed the councilor a written request about the institution of the date in Ubatuba. In justifying the importance of the proposition, Melisa cites the passage of 172 Japanese immigrants through the Ilha Anchieta prison from 1946 onwards. The councilor showed interest and said he would present a bill soon.

The idea comes a year after the institution of the Day for Bulgarian immigrants and Basrabian Gagaúzos in the Ubatuba calendar, which remembers the death of 151 people on Anchieta Island in 1926, just 20 years before the arrest of the Japanese. As you can see, the island was a beautiful setting for tragic stories, such as those about immigrants or the prisoner rebellion in 1952.

Interestingly, the prison finished being built in 1908, the year that marks the beginning of Japanese immigration to Brazil. Next year, in 2018, we will celebrate 110 years since the arrival of Asians in Brazilian lands.

Although there were some involved in cases of political assassinations within the context of the conflict between the so-called “victorists” and “defeatists”, the majority of those arrested were innocent.

To understand why these innocent people were arrested, it is necessary to look at the political context of the time. This is what researcher Mario Jun Okuhara did, who released the documentary “Yami no Ichinichi – The crime that shook the Japanese Colony in Brazil” in 2012.

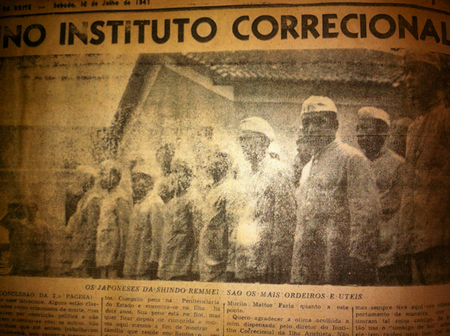

The documentary presents the historical context taking as its starting point the memories of Mr. Tokuichi Hidaka, arrested on the island in 1946 for his involvement in the murder of Colonel Jinsaku Wakiyama, in a crime attributed to the entity Shindo Renmei (League of the Paths of Subjects). In the film, Hidaka returns to Anchieta island, in Ubatuba, and recalls daily life during the prison era, walking through the ruins of the prison, in a rich and detailed account of this historical fact.

INTERVIEW WITH MARIO JUN OKUHARA

This Monday (29), we interviewed the author of the documentary to find out more about the prisoners on Anchieta Island and the political context at that time. According to Mario Jun Okuhara, at the time of Getúlio Vargas' Estado Novo (1937-1946), the Second World War (1939-1945) and the post-war period with military president Eurico Gaspar Dutra (1946-1951) there was legislation of repression of immigrants.

The documentary filmmaker observes that due to the “culture of shame”, little is said about the way the Brazilian State treated Japanese immigrants (and others).

An example is Decree-Law No. 383, of April 1938, which prohibits foreigners from political activity in Brazil. The following month, Decree-Law No. 406 was instituted, whose article 2 establishes that “the Federal Government reserves the right to limit or suspend, for economic or social reasons, the entry of individuals of certain races or origins, after consulting the Council of Immigration and Colonization” . The regulations of this decree also provided that publications of any books, leaflets, magazines, newspapers and bulletins in a foreign language would be subject to authorization and prior registration with the Ministry of Justice.

When in 1942 Brazil decided to break diplomatically and commercially with the Axis countries (Japan, Germany and Italy), the lives of immigrants from these countries became even more difficult here. Vargas institutes Decree-Law 4,166 , establishing that the losses caused by the Axis countries to Brazil would be paid by the immigrants. The government taxed bank deposits from German, Japanese and Italian immigrants by up to 30%.

At the end of the second war (1945), part of the Japanese colony in Brazil did not believe in Japan's defeat, believing that the news circulating about the surrender of the Emperor of Japan was false. This generated conflict between those who believed in victory and those who admitted the country's defeat. It is in this troubled context that the Japanese arrive on Anchieta Island.

For Mario, the arrest of Japanese immigrants on Anchieta Island is an interesting case because there is a lack of memory spaces from that time. “This emblematic case on Anchieta Island not only reveals these violations against the human rights of these Japanese people in that post-war period, but it rescues everything that was done previously. There is a continuous line of violations that were carried out without interruption” , says Okuhara.

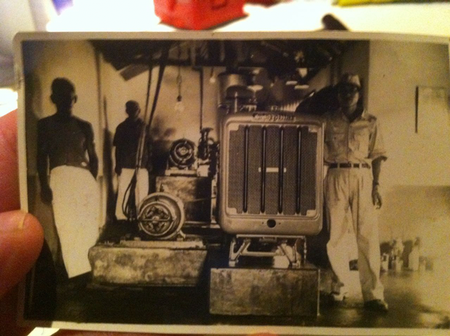

In addition to the ruins of the prison, there is a generator on the island from immigrant times that was repaired by two Japanese prisoners. The intention is for this generator to be exposed to visitors to the island, which is currently a State government Conservation Unit that receives tourists from different places.

“The institution of the day for Japanese immigrants in Ubatuba will strengthen the exposure of this generator, strengthen memory and encourage people to continue researching, because there is still a lot to be written” , said Okuhara.

The Japanese's stay on the island was marked by improvements in the functioning of the prison. “They organized themselves into skills. There was no shortage of farmers. There was a tailor, two 'mechanical engineers' and a series of professions to compensate for the prison's shortcomings,” said Mario. It is known that they fished, held a sumo championship and managed to create a vegetable garden, diversifying the prisoners' diet.

And what happened to these immigrants? According to Okuhara, those who committed the attacks served their sentences and the rest, who were innocent, obtained habeas corpus and returned home.

TRUTH COMMISSION

In October 2013, a public hearing was held on the “Cases of torture and death of Japanese immigrants – 1946 and 1947” at the Legislative Assembly of the State of São Paulo. The event occurred after the repercussion of Okuhara's documentary. “They told me that I had a complaint of political persecution and repression and all the violence that a dictatorship causes and they suggested looking for the Truth Commission” , said Mario.

The Truth Commission of the State of São Paulo “Rubens Paiva” addressed the case of the 172 Japanese detained at the Ilha Anchieta Correctional Institute, with testimonies of the violations against Fusatoshi Yamauchi and Fukuo Ikeda. According to Mario, the reports presented at the public hearing were able to verify an objective situation of exceptional acts carried out by agents of the Brazilian State against Japanese citizens.

LISTEN TO INFORMAR UBATUBA’S INTERVIEW WITH MARIO JUN OKUHARA:

* This article was originally published in InforMar Ubatuba – Notícias & Turismo on June 1, 2017.

© 2018 Renata Takahashi