Who inspires me to be better? I think my oba does. Although I still don’t know how she overcame so many challenges, became successful, and helped others. And just like a heroine, she never expected anything in return.

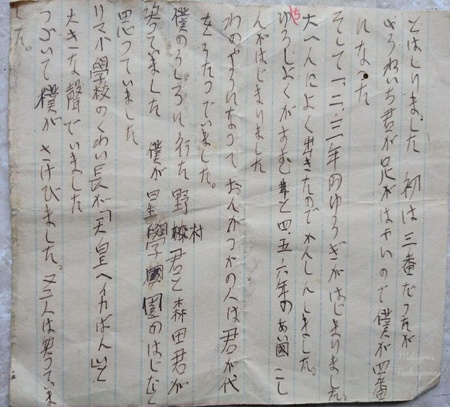

My oba was 92 when she died and I was 9. The difference in our ages was more than 80 years! I think that gave my oba a certain “halo” of mystery. She never told me the story of her life. She rarely spoke spontaneously; just four or five words at a time and I’ve been storing them in my memory. Actually, her Spanish wasn't much help. When I was 30 years old I started to reconstruct my oba’s life story based on my mother’s memories, notes that I found on the backs of old photos, documents that were so old they disintegrated, and even by Googling on the Internet to check them against historical events. My oba told my mother about the shizoku origins of the family even though she didn’t know how to explain her own history. She is my oba on my mother's side and I lived with her for 9 years.

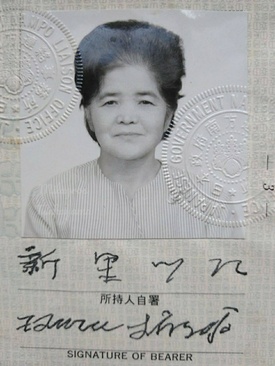

My oba’s name was Tsuru Shiroma; her name was changed to Tsuru Shinzato when she got married. After converting to Catholicism she chose the name of Isabel. And among her fellow Japanese immigrants in the neighborhood, she was known as Malambito obasan (because her business was located on Malambito Street). Oba, as the family called her, arrived in Peru in October 1918 on board the Anyo Maru. “It was her honeymoon,” my mother told me. My oba was 21 years-old and had recently married. She and oji (my grandfather) chose Peru as their destination thinking they would only live there temporarily.

They worked at the Paramonga sugar plantation, for an unknown period of time but the way I discovered that fact still makes me smile even today. One day I went crying to my oba carrying a roll of toilet paper in my hand. “They called me monga,” I told her. My older sister had played a joke on me and gave me the roll of toilet paper, saying “Para monga” (“for monga”), making a pun. “Para monga” referred to the name of the Paramonga factory that made the toilet paper, but “monga” also means “stupid”. As if it were a spark of nostalgia oba looked at the toilet paper and said in broken Spanish: “Why does that bother you? I worked at Paramonga,” and that was it. I was just five years-old so I didn't understand what she meant. But with similar anecdotes it was as if I compiled her own life story.

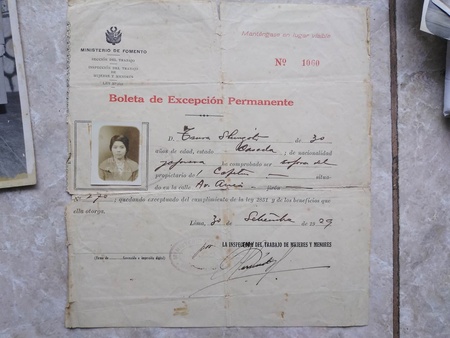

No one in the family knows much about what happened in the years immediately following my grandparents’ arrival in Peru. But in 1929 oba and oji opened a small café according to a document that I still have in my possession.

Years later, she bought the “ranch” that we all knew even her grandchildren. It was a bakery but my grandparents converted it into a cafe as well as their home. They called it a ranch because it had an area of 200 square meters. But as people began leaving, its vastness became more noticeable. The war was to blame. My oba sent the older children to Okinawa to study. The chonan (oldest son) attended the Okinawa Ken Ritsu Dai Ni Chuugakko secondary school. But, when Japan began recruiting people for the army Chisei decided to stay and fight, while his sisters sought refuge in Naichi (Japan).

“He didn't have to do it,” my oba said according to my mother. Because he was the chonan, he was allowed to choose whether to go with his family or stay and fight. “But they brainwashed him,” my mother said. So many false promises, which cut short his future and my oba’s hopes. A bomb fell on the place where my uncle was assigned. Although they didn’t find the body, the news came quickly. Not even the compensation money that my oba received helped alleviate her deep sadness. But, I have to acknowledge that it did save us during another struggle: surviving an economic crisis. It was the mid-1980s when my father died and in Peru the economic crisis was severe. My mother had become a widow and her sole means of support at that time was my oba. With oba’s help we managed to survive. Oba gave us part of the compensation funds that she received each month, so that we wouldn’t lack for anything.

When she was widowed, my mother's experience was almost identical to that of my oba. She had small children, a business to run, and the grief of losing a life partner who hadn’t even reached his 50th birthday. But my mother was lucky to have the support of her mother, my oba. My oba, on the other hand, only had herself and a few close relatives to rely on when she became a widow.

I never saw her cry or complain. And the memory that is still etched in my mind is oba in her bedroom sitting on the bed or in a chair smoking silently, her gaze lost on the wall. “To keep herself company in her solitude,” my mother said. And it's true. Silence can sometimes be the best company or the best balm for alleviating sorrow for the family she left in Okinawa, the husband or son who is no longer there, or the bad decisions she made thinking they were the right ones, always thinking about the family.

My oba was successful in business at the café that many referred to as “the gold mine.” But she never had that ambition that everyone now says you should have, the kind that’s called “entrepreneurial vision.” My oba never thought about expanding the café or opening a second one and was happy with the café she had opened along with her husband. It remained in business for more than 50 years. “It's enough for me that the family is together and doing well,” she seemed to say. I don't think money mattered to her very much and in fact, she shared it with her family.

When she traveled to Okinawa to visit her family after the war she brought them gold watches, rings, and bracelets as souvenirs or omiyage because, she said, “There is no gold in Nihon.” Deep down she knew that her gifts would help pay for the things they needed. And she often “loaned” money to family members and close friends in Peru although she never expected anything in return. My oba was very good to my father and I think she viewed him as the son she had lost.

Despite all of the problems she faced, oba never lost her desire to keep going and succeed. Maybe she was motivated by the affection of her family; I’m not sure.

My oba was so reserved that even in photos she rarely smiled. Although later I discovered that one’s face reflects all of life’s hard knocks and it can harden your gestures even on the happiest day of your life such as when your youngest daughter gets married or your first grandchild is born. My oba carried her sorrow inside so much it seems that she began to hide her happiness inside as well. I can't imagine how hard life must have been in her time with a war that caused anti-Japanese prejudice in the West, being a woman running a business alone, and the latent sexist mentality of that time. My oba never became a Peruvian citizen and never forgot to renew her passport. “Some day,” maybe. I think she always wanted to return to Okinawa just as she and my oji had planned. But once her grandchildren were born in Peru perhaps that desire gradually disappeared like the puffs of smoke from her cigarette.

But even so with her “strange” customs, her “magic words” that cured almost everything and that in reality were unchinaaguchi (the Okinawan language) like the mabuyaa to help me when I was scared or the chino miku miku duu gan jyuukupara that “always has” new clothes; all of that made her even more mysterious. Especially the silence that became part of her to hide her sadness and keep her family from worrying. Although she wasn’t even five feet tall and spoke broken or “chewed up” Spanish my oba inspired respect. We could never use the informal Spanish “tu” when speaking to her and always used the formal “usted” even though she never asked us to. I believe that my oba had what makes heroes inspiring: you respected her for what she had experienced and what she had done. Although she left us 30 years ago my oba continues to inspire (and surprise) me. She passed away on November 25, 1989.

© 2019 Milagros Tsukayama Shinzato