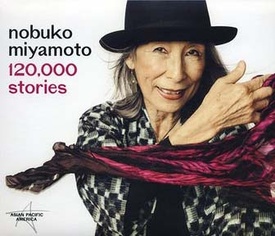

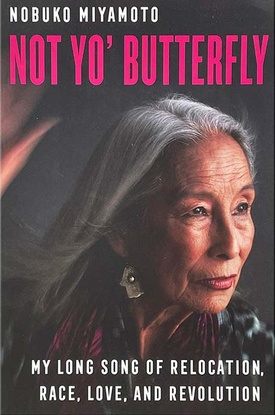

Despite the pandemic, 2021 was a landmark year for Great Leap Artistic Director and activist, Nobuko Miyamoto. Her autobiography, Not Yo’ Butterfly, My Long Song of Relocation, Race,Love, and Revolution was published in June by the University of California Press. Her double CD set, 120,000 Songs, was released in February by Smithsonian Folkways and included new songs as well as re-recorded oldies. A Nobuko Miyamoto Christmas Ornament was featured in the Japanese American National Museum’s (JANM) holiday catalog (the previous year's catalog featured an ornament honoring Yuri Kochiyama).

Looking forward to this year’s events: February 19 and 20, 2022, Nobuko will perform a live concert of 120,000 Songs for Day of Remembrance at the Getty Center, cosponsored by JANM. Her interview will be featured on NPR’s program Snap Judgment. She is creating a new Obon piece and planning another FandangObon with producer Alison De La Cruz. She will also be featured in an episode of KCET’s Artbound in the fall.

After Detroit activist/philosopher Grace Lee Boggs advised Nobuko to write a book, she began working on it in small segments for six years. Her autobiography is divided into three “movements” like a performance. Each section covers a different “movement” of her life: childhood/dance training, political activism, and single motherhood/artistic life. She transitions from shy JoAnne (“JoJo” as a child) to Nobuko, finding her voice through political activism and performance. Her Intro poem sings, “i grew up without a song that sang me.”

Nobuko's journey takes her from concentration camp at Santa Anita racetrack to performing in Hollywood musicals such as Flower Drum Song and West Side Story (with Rita Moreno). She leaves Hollywood for New York and becomes a revolutionary political activist. She writes and performs songs about Asian American identity with activist/musician, Chris Iijima. Along the way, she falls in love and has her son, Kamau. Kamau's father, Attallah Ayubbi, is shot and killed while planning a Harlem mosque. Nobuko continues on through single motherhood, bonding with the Senshin Temple (Los Angeles) community, and creating Asian American art. She founded the nonprofit arts organization, Great Leap, in 1978. She is married to artist Tarabu Betserai Kirkland.

Not Yo’ Butterfly is a story about resilience and struggle, about Nobuko finding her voice. It is about how the past civil rights struggles are connected to the present Black Lives Matter movement and current struggles. It expresses optimism despite the threat of global warming, pandemic, and political strife. Above all, it is about the love and support of family and community, which make life worth living.

We spoke via Zoom on December 2, 2021. This interview has been edited.

* * * * *

Why Asians need a voice:

I feel even now that Asians need a voice. They need diverse voices. They need to be heard, they need to be seen. And these last two years have been a testament to that reality. The violence against Asians and the easy riling up of these old stereotypes that made it easy for people to violate our rights and (not) see us as human beings. The metaphor of song is so we’re not invisible. We each have a song, we each have a story. We each have something to say.

On the title of the book:

The book was originally called What Can a Song Do? But the publisher didn't think that was a catching title. So then he pushed me to find something more provoking, I guess. Then I searched and searched and I finally went back to a song called Not Yo' Butterfly. It was on the album and when he heard it he said, “That's it.” And he said, “I like the Yo'.” That's a black colloquial word. He said, “Because your life defends it. Your life stands up to that.” So that's why we ended up with Not Yo' Butterfly.

On writing a book:

What writing the book was really, was sort of a retreat for me and deep moments of reflection. Because in all these years of living and working, and being a single mother, and running an arts organization, I have not had time to sit and reflect on my work or my life. And having Grace Lee Boggs tell me it was time for me to write my book. She was again teaching me a lesson, I think. She said it changed her life to do that.

She was a philosopher and she had written other books. But when she wrote her personal story it (not only) shifted something inside of her but it also shifted how people looked at her. And it has really helped me look at the big picture of my life as I enter my eighth decade. It was sort of a good way to look at my life as a whole. Which one rarely does, really.

The one thing that struck me about your early childhood memories was how vivid they were. At a very young age you had very vivid memories.

It was a lot of trauma actually in those early years. Trauma of being uprooted with my parents. I think my parents felt it terribly. But a child feels it and sort of just goes along with it. A lot of those stories also are stories that my mother told me as well, because it affected her and for seven years I was the only child. And those years my father was working, so my mother talked to me a lot.

And I didn't have a lot of playmates because we were moving around. So my mother she was company for me and I was company for her. And she expressed her anger about being put in camp. So I think that's why I held onto some of those memories as well as I did is because it was part of her memory as well.

Your relatives said you resemble your great-grandmother Hatsu (in Japan).

Yes, and that was a strange thing. I went there (Japan) feeling and fearing that I wouldn’t be accepted as being a real Japanese because I was mixed. Even in the US here, most Japanese people don’t see me as looking like a Japanese person. So when I went there, I was prepared to be the outsider that I’ve always been.

And when they were so good to me in the family, you know, they cooked a beautiful meal and just showed us around. They were just so gracious. And before I left, one of the aunties who looked like my auntie (in the U.S.) said, “You look like your great-grandmother. You even move like her. Your gestures are like her.”

So that like freaked me out because here I thought that I was not really Japanese. And here I was with my real relatives who thought that I was my great-grandmother incarnate in a way, coming to visit them. And so that was a deep experience for me. I’m so glad I was able to experience that and know that. It made me see myself differently. It really did.

You had a supernatural experience (in Japan) where you heard your grandmother say “Forgive me” and you felt her presence.

Yes, and that was because I had been hearing Nihongo for days and my mother’s stories we’ve been talking about my mother’s stories and her being in Japan. And with someone who knew my mother as a child, so all of this energy was swirling around me. And I brought a little bit of my mother’s ashes with me. And I had it in my pocket and I wanted to leave her ashes there with her mother. It ended up I couldn’t do that, but the fact that I was trying to resolve a trauma for my mother of losing her mother who committed suicide. And trying to figure out why she would leave her children when they had just been reunited. Why did she do that?

I know you were worried going there about being accepted. I liked that family member, who when he saw all the pictures that you brought said, “Our family very international.”

Yes, that was a hard moment. As I said, I didn’t think I would be accepted as being Japanese. I had to figure out a way to make us acceptable to people that I thought may not be that open to having black great-grandchildren, etc. So by showing a picture of my mother in Japan with her family and showing the journey that we had gone through and the last picture was Kamau (Nobuko's son) with his black wife. It was obviously he was Muslim, obviously he was black with his black children and wife. And how beautifully they accepted it, you know. It just broke my expectations and my fears.

You shared in your book how your mother initially had a big adjustment before Kamau was born. You left her in the room and she was just crying. But then she came about when you got out of the hospital.

And then I was thinking that it’s racism. But then when I went deeper I realized that she was fearful that this child would be treated badly because he was black. And she didn’t want her children to be treated badly, you know. But I didn’t get that at first. I just thought, “Oh, she just can’t get it. Can’t you get it?” So when she came over the day after I got out of the hospital with chicken soup, I was like, “Oh my god! She got over it! She got through this! I don’t know how she did it, but I’m glad she did it.” And then I realized how much I needed her.

I thought that it was nice how his family, Attallah’s (Kamau’s father) family in New York, like Grandma Jeffreys, kind of helped you.

The family in New York including Yuri Kochiyama’s kids who had mixed children as well, Zulu and Akemi, were like really good cousins for Kamau. Mixed children have a way of connecting with other mixed children. For some reason, I noticed that they need affirmation that there’s other people like me. So being close to his family who also needed Kamau.

I think Grandma Jeffreys saw in Kamau her lost son. And that was a replacement for her loss as well. So that’s what that family, and we’re still close after all these years. It’s been almost 48 years now that we see each other and we talk to each other. And you know, we see each other as family and it’s been such a gift to have that relationship.

I think it’s kind of neat that Tarabu (Nobuko’s husband) did tai chi. You talk about his chi. You talked about how he cast you in Juke Box with Danny Glover as part of an interracial couple.

I was trying to write a musical about Holiday Bowl, you know, the bowling alley. And Tarabu was writing a musical that was in Oakland about this restaurant with this interracial couple. A friend of ours said, “You two should meet because you’re working on this project that is very similar.” And so when he finished the project he came down and asked me if I would be in this musical. And I said, “I don’t have time to do that. Thank you.” But then he said, “Well, Danny Glover is going to play the husband.” So what it did, it gave me a chance to see what an artist Tarabu was. And how he worked, his diligence and his artistry. And to see somebody in action like that, you get to know who they are really quickly. And I had a lot of respect for his work and his ethics and values. So I asked him to marry me!

So I just wanted to talk about Kamau. He had a lot of adventures and there were a lot of things that surprised you. He said, “Mom, I’m going to Casablanca.” I know you worried about that until he came back safely. Then there were other surprises when he called and said, “Mom, I’m a Muslim.”

You know this little kid was so, we were so close because, of course, it was just the two of us for almost thirteen years. So we were very, very close and he was with me always. So it was pretty hard to be separated from him and it was hard, I think, even for Tarabu to move into our life. So when he went off to school and he started managing his own life, I was shocked at the kind of independence like where he leapt before he looked where he was leaping into. I don’t know where he got that from. But he just fearlessly would go do things unexpectedly, you know.

But becoming a Muslim? That was scary for me. Not because I didn’t like Muslims but because of what happened to his father. And it’s not so easy for you as a parent. But in the long run it makes you grow as a person. Then you stretch and you relax and you open up like my mother did. And she totally embraced Kamau. I don’t think there was anybody as close to their grandchild as she was to Kamau. She truly just loved him, she just embraced him one hundred percent. And that love really made her look at race in a different way.

© 2022 Edna Horiuchi