As Nikkei, we have inherited a culture that our ancestors brought from Japan. My grandparents, who emigrated from Okinawa, have seen some of their customs adapted to our country. Meanwhile, other customs have been preserved to the letter, even when they’ve been forgotten in their place of origin as if they’d been frozen in time. Sometimes I feel like we have grown up loving the idealized place that they have maintained in their minds.

In Peru, we have a small business called “Chawakí and Something More” that was established to prepare offerings for the butsudan (an altar for venerating the dead) and other food to continue the custom of honoring those who have passed along with the preparation of traditional dishes. Many of us who maintain these customs continue to practice them as we have been taught even though they have since changed in Okinawa. Others have chosen to simplify things and among more recent generations some forego tradition as representing the rigidity of certain ancestors.

Cooking is part of culture. Those of us who want to maintain these traditions want to learn more about the types of food we prepare. In this case, a sweet cake that originated on the island and which we call nantu, the mochi of Uchina.

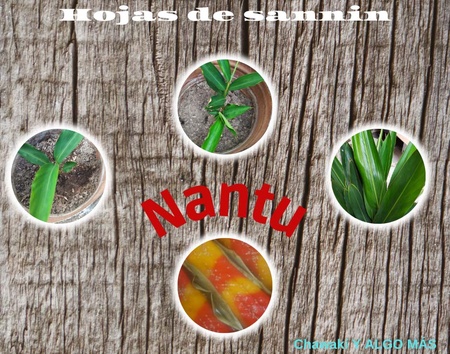

Our nantu is made with glutinous rice flour (mochigo) to which we add sweet potato, sugar, miso, sesame, and vegetable coloring. Some people divide the mochi into parts: the sweet potato we use in our country is a color between ochre and yellow and the other part is dyed red. Although, some use green dye. Many years ago, when rice flour wasn’t available, they used ground rice as a substitute mixing the dough with water. The dough has to be kneaded for a while. Then we place the mochi on sanniba or ginger leaves (which we call “kion”) for steaming.

As a food business, we have a social media presence which has enabled us to connect with many more people; even outside our country. When we posted photos of our nantu, a Nikkei woman in Argentina was surprised by how colorful our mochi is. She commented that it’s not made that way in her country or in Okinawa. After doing some research I was surprised to find that the nantu we eat in Peru is not the same as in Okinawa.

What I found is that in Okinawa they make mochi from miso, brown sugar, and peanut paste (himami, which means island peanut) and cover it in sesame seeds. There are also some mochi that are made with purple sweet potato also known as taro (taanmu in Uchinaguchi). While we use vegetable-based colors, their mochi were a single color. Some were brown from the miso and others were purple because of the sweet potato which is different from Peru. In Okinawa there is an almost infinite variety of this sweet cake using mango, squash, and dragon fruit (known as pitahaya in Peru). Also, they wrap everything in the sannin leaves while we simply place the leaves underneath.

I wonder why our nantu is different from the nantu made in Okinawa. The first thing that comes to mind is seeing it when I was a child. That colorful little cake that was like chewing gum when you put it in your mouth with a sweetness accompanied by a scent that was different from the leaf. Although, this was gum you could eat and not just chew. Nantu is part of all celebrations in our house, with relatives, friends, or other Japanese descendants. What makes it so appealing are the colors. The red with ochre and sometimes green. The ochre color comes from our country’s sweet potato and the red is used, I suppose, because it’s a festive color.

Most immigrants worked in agriculture when they came to Peru. Some stayed in the countryside. In those days there was no glutinous rice flour which modernity has since brought to us. The sweet potato wasn’t the same as it was in the immigrants’ places of origin. That’s why the color is different. And perhaps because it was used for festivities they complemented it with striking colors. The big question is why it became common in all of Peru’s Nikkei households. I suppose our community was always very centralized and most people met in Lima, Peru’s capital, through associations, clubs, and groups of people from Okinawa known as the shimanchu (“from the same town” in Okinawan).

In some parts of the city it was common to see Nikkei families with businesses located in close proximity to each other. In the countryside they also had neighboring agricultural plots which we call chacras (a term used in Latin America from the Quechua word “chakra”). That’s why many Nikkei families frequently came together for work and life celebrations. Japanese immigrants, neighbors, friends, and family provided mutual support.

The men were in charge of setting up the place where the festivities would take place with large boards placed on sawhorses to serve as tables along with long wooden benches. Meanwhile, in the kitchen the women were in charge of preparing all the food. One of the sweets was nantu which required large pots of water with empty milk cans at the bottom topped by trays with all the nantu that could fit in one batch so they could be steamed. From a certain distance you could smell the characteristic scent of the leaves. According to beliefs on the little island of Okinawa, these strong smells could keep evil spirits away.

At our business, Chawakí and Something More, nantu is very important to us. In Peru when the pandemic started, groups formed on Facebook to buy and sell products. These groups included Nikkei and all the people who, even though they are not Nikkei, want to be part of our community. That’s how we helped each other. I remember one person asking where they could buy nantu; another person recommended our business. At the time we weren’t able to make nantu because we didn’t have sannin leaves. I asked forgiveness on the part of our business. Several people responded with an offer of leaves so that we could resume making it, which was something I never expected.

Eventually, the person who was looking for nantu offered me the leaves and even a plant so that I could cultivate it myself. Since I don’t have a garden I planted it in a pot and other people donated more plants. Today, when I see them in my house growing taller, they seem to represent Nikkei solidarity in difficult times like the pandemic. I believe that it brought out the best of every person and of our community.

* * * * *

Our Editorial Committee member selected this article as the favorite Itadakimasu 3! Nikkei Food, Family, and Community story in Spanish. Here is his comment:

Comment from Javier García Wong-Kit

I chose this article because of its value from a historical, family, and scientific point of view. Through mochi, an essential element of Japanese and Nikkei cuisine, we’re able to understand the importance of food in the migration process, especially for the Japanese community in Latin America and its origins on Okinawa. I think we can learn a lot from this story, not only about Japan but also about what happens in Peru. It’s also an anecdote about how traditions unify the Nikkei community and the value of preserving traditional practices when starting a family enterprise like so many Nikkei businesses around the world.

© 2022 Roberto Oshiro Teruya