Once, when I wandered into a jazz bar run by a Japanese person in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, I had a chance to talk to a local Japanese person who seemed to be a regular. The person, who had lived in the area for many years, told me various things about the local Japanese people during my travels. He said, "There are some people who, for various reasons, can't stay in Japan and have come here."

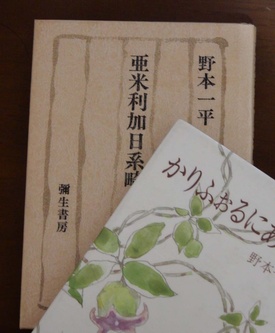

The other day, I was reminded of these words when I read "Amerika Nikkei Kyojinden" (Yayoi Shobo), written by Ippei Nomoto, published in 1990. Although it goes back a long way from the Japanese person I was talking about at the bar, when I traced the lives of the first generation of Japanese who left Japan for America, I felt deeply that "I see, there must have been various circumstances that led to this."

I knew the name Ippei Nomoto, but this was the first time I read his work. His natural, calm, and intellectual writing gives you an idea of what kind of person he is, and reading the reviews of him, I found that to be the case, as he truly was the embodiment of the saying, "The writing is the person."

Mr. Ikeda, who lived in California and contributed to the local Japanese newspaper, "Rafu Shimpo," passed away on February 27, 2021, at the age of 88. Based on the memorial article at the time of his death and the profile in the colophon of this book, I will summarize his achievements below.

Nomoto Ippei (real name Norimoto Keizo) was born in 1932 (Showa 7) at a temple in Maesawa-cho, Iwate Prefecture (now Oshu City), and graduated from the Faculty of Letters at Ryukoku University in Kyoto. After working as a teacher at Musashino Women's College, he visited the United States for the first time in 1962 as part of a delegation of monks celebrating the 70th anniversary of Buddhism in the United States. In 1965, he became the missionary of Nishi Honganji Betsuin in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, and in 1976 he was transferred to Fresno Betsuin in central California.

He worked as a writer under the pen name Nomoto Ippei. He published biographies and essays about Japanese and Japanese-Americans living in the United States. After retiring from the Buddhist Association of America at the age of 65, he served as president of the San Francisco-based newspaper for Japanese people, North American Mainichi. In 2010, he was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Rays by the Japanese government for his contributions to the promotion of Japanese language education in the United States and the welfare of Japanese people.

Shining a light on the lives of the Issei

As the Rafu Shimpo article states, perhaps because Nomoto himself is a first-generation immigrant to America, he writes about the characters and lives of his fellow Japanese from the perspective of a Japanese living in America, shedding light on the lives of his fellow Japanese. In particular, he has tried to introduce people who have not received much attention.

However, this is particularly intriguing, because the people he is interested in are mostly Issei. Of course, every life has its own drama, but the Issei all lived a life that was almost like an adventure, traveling from Japan to America. Each person had different reasons for moving to America, such as ambition, escape, or poverty, and it was undoubtedly a major turning point in their lives.

It is easy to imagine that there must have been lives buried in a foreign land filled with complex emotions that cannot be expressed simply as success or failure. "Amerika Nikkei Eccentric Biography" is a careful collection of the various lives of these Issei.

Meiji Japanese

This book is a critical biography of 12 people who migrated from Japan to America in the early to mid-20th century. What all these people have in common is that they were all born in the Meiji era, lived and died in America, far from their homelands.

Some of them are famous people, such as Hideyo Noguchi, but most of them were not famous in their home countries. In addition, Noguchi is not a well-known success story as a scholar, but a very human side, and each of them delves into their way of life and inner thoughts.

For example, there was Kojiro Tomita, a curator at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. He was a disciple of Tenshin Okakura, who contributed to the museum as head of the Oriental Department during the Meiji period, and was one of the last people to receive his tutelage. He was an old-fashioned Meiji man who lived an honest and modest life.

Shimoyama Isso is introduced as a "wandering Japanese haiku poet." Born in Morioka and a member of a nationalistic society, Shimoyama went to the United States, promising to become a member of parliament in the future, but once in America, he wandered from place to place within California, and ended his life as a free-style haiku poet.

While working at a farm, a fishmonger, and a cannery, he devoted his passion to composing haiku. He founded a haiku society and taught its members. He had a love affair with a married woman, then lost her, and in later years struggled with illness. Nomoto carefully follows his difficult life with a sympathetic gaze.

Sakai Yoneo, who was active in the world of journalism from before the war to the postwar period, appears as "the last Issei journalist." Sakai traveled to Europe, North Africa, Asia, and other places before the war, and published "Vagabond Tsuushin" through Kaizosha. He was also the only Japanese journalist to have covered the Spanish Civil War on site.

Also connected to journalism were Fujii Ryoichi and Fujii Sei. Fujii Ryoichi was a pastor in Japan, but after moving to the United States he joined the American Communist Party, eventually breaking away from the party and launching the Chicago Shimpo, a Japanese newspaper, in Chicago after the war.

Fujii Sei was a skilled journalist and a leader in the Japanese community, having served as president and editor-in-chief of the California Mainichi Shimbun, which was first published in 1931. However, he also had a dark side to him personally, as he left his wife and children behind in Japan and never returned. The author also touches on the circumstances that led to this.

Another example is Tamai Yoshitaka, a priest of the Jodo Shinshu Nishi Honganji sect who died in Denver, Colorado, who left his wife and children behind in Japan. Tamai was a compassionate man who devoted himself to his fellow countrymen and was loved by the Japanese community, but he left his wife and children behind in Japan when he went to the United States. His wife became mentally ill, and his eldest son was killed in the war. The author's writing is heavy and quiet, as he surmise the feelings of Tamai, who never spoke about his wife and children.

After moving to the United States, Joe Koide became a member of the American Communist Party and was involved in revolutionary activities in his native Japan, and during the war, he worked as an intelligence agent for the U.S. government, working on espionage activities to force Japan to surrender. In order to hide his identity, he abandoned his real name, Nobumichi Ukai, and assumed the name of a real person named Teiji Koide, calling himself Joe Koide, and ended his life under that name. This book introduces his extraordinary life.

In the afterword, Nomoto Ippei writes:

"They do not live what would be called ideal lives. They take detours, stumble, and take a winding path, but still they continue to burn with life and live their lives to the fullest. That is why they are called 'freaks.' This humble essay is also my elegy to them."

© 2022 Ryusuke Kawai