At the start of 1942, Japanese immigrant communities living in diverse areas of North America started to live days of torment. The attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces in December of 1941 not only unleashed war between Japan and the United States but also meant the beginning of a life filled with persecution and seclusion of Japanese immigrants and their families.

The United States government believed that the community of Japanese immigrants that had lived for more than forty years in the US and Mexico was part of a ploy by the imperial Japanese army to invade the North American continent. This paranoia (officially accepted by government officials) enabled the US government to detain more than 120,000 Japanese citizens, of whom two-thirds were US citizens, in ten concentration camps.

As requested by the US, Mexican authorities ordered Japanese immigrants living across the country to travel by their own resources to Mexico City and Guadalajara to be meticulously monitored.

In the Northern Mexican states of Baja California, Sonora, and Sinaloa, there lived more than 2,000 immigrants who were the first groups to be displaced under the petition of the United States. These Japanese immigrants had begun to move to those regions of Mexico to work in the mines, agricultural fields, fishing industry, and commerce. The majority of Japanese immigrants had already settled in various cities in those states with their extended families and had children already born in Mexico.

American General John Dewitt was one of the prominent people responsible for requesting President Franklin D. Roosevelt to move all Japanese living in the United States. He also ensured that all the immigrants in Mexico residing on the border were sent to other regions. The mobilization of the Japanese in Mexico was closely related to the racist thinking of General Dewitt, who considered "dangerous" not only the children of immigrants but even the fourth-generation descendants who continued to conserve the "same blood ties."

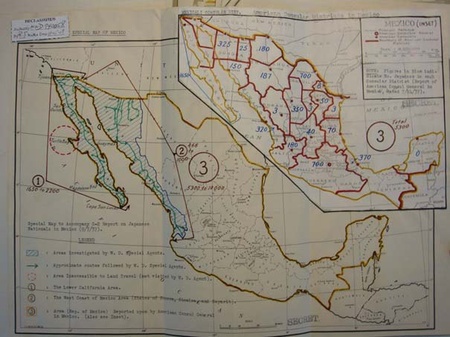

It is important to note that US intelligence carefully watched Japanese communities in Mexico in previous years. US government agencies and the FBI gathered data on the number of Japanese immigrants, activities, and locations, as seen on the map.

In December of 1941, at the start of the War, Japanese families in Sonora finished the year with great anguish and uncertainty about their future. Since their arrival in their new home, they celebrated Christmas even though it was not a Japanese tradition. On Christmas Eve, they would traditionally eat Mexican dishes like tamales and roasted turkey, which was very popular due to the proximity of the US. Japanese immigrants remembered to celebrate their traditions, like their Japanese New Year shogatsu, and eat customary Japanese food like osechi. To prepare Japanese dishes (o-zoni, mochi, toshikoshi soba), they would travel to the US border to purchase their ingredients from Japanese stores owned by their fellow countryman.

Asaji Katase was one of the immigrants residing in Sonora for 20 years before the war. Katase arrived in Mexico in 1917 when he was only seventeen years old. Upon his arrival in Mexico, some Japanese groups were already established around that area and he would start employment at a ranch managed by Mr. Ryukichi Abe.

By 1929, Katase worked and saved money to acquire a small property in El Tazajal, where he cultivated vegetables and raised cattle. Without the possibility of returning to Japan, he sent Chizuko Tanaka a letter with his photograph and marriage proposal requesting her to move to Mexico and start a family. Tanaka, who was from the same community as Katase in the prefecture of Nagano, arrived in Mexico in 1930. At the start of the war, the Katase family had fully integrated into the Sonoran community and had five of their six children.

In May of 1942, following the order of authorities, the Katase family arrived in Mexico City along with their children, the youngest, Artemisa Mitsuko, who was only six months old. The first thing they did when they arrived in Mexico City was to report to the Department of Government to inform them of their arrival and where they would be located. The Mutal Aid Committee, kyoeikai, was the organization that offered support to the Japanese communities that arrived in Mexico City. The objective of this committee was to provide support to the internees in looking for a home and employment.

The Katase family moved to the city's southern area in the Tlalpan neighborhood, where a group of the internees already lived and came from diverse areas of Mexico. The Katases produced milk candies that Asaji would sell near the Buenavista train station and guide newly arrived tourists to nearby hotels.

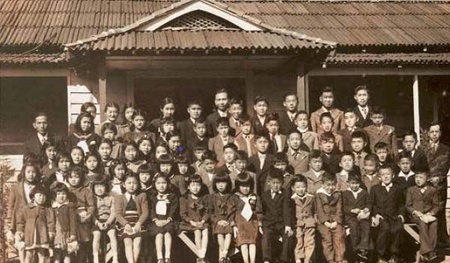

The Japanese concentration enabled them to reinforce a strong community based on mutual support to solve the problems that carried the war and persecution. One fundamental worry that Japanese immigrants had was the education of their children. Acknowledging the educational system in Mexico, the children were admitted to free-of-cost public schools in the Tlalpan neighborhood.

Furthermore, the Japanese communities that lived in various city areas established their own schools for the children to learn their language and customs. Japanese immigrants would provide a significant amount of their income to employ educators and have the proper tools and resources so their schools would function adequately. The concern and dedication of Japanese communities for their children's education made it possible for their children to enroll in universities and become professionals.

At the end of the war in 1945 the Department of the Interior allowed the Japanese to return to their homes and freely move around the territory. The majority of Japanese immigrants decided to stay in Guadalajara and Mexico City because they had already comfortably set roots and, most importantly, their children would have access to high-level schools.

The Katase family decided to return to Hermosillo and open a successful grocery store, "Cali Vonten," that comfortably sustained their large family. The older children decided to move to Mexico City where they became doctors and the rest became accountants, dentists, and one of the daughters graduated as a musical performer. To this day, the children and grandchildren of Asaji and Chizuko have received notable recognition from the Sonoran state for all their extraordinary work.

* Thank you to Patricia Katase for her help and cooperation to make this article.

© 2003 Sergio Hernandez Galindo