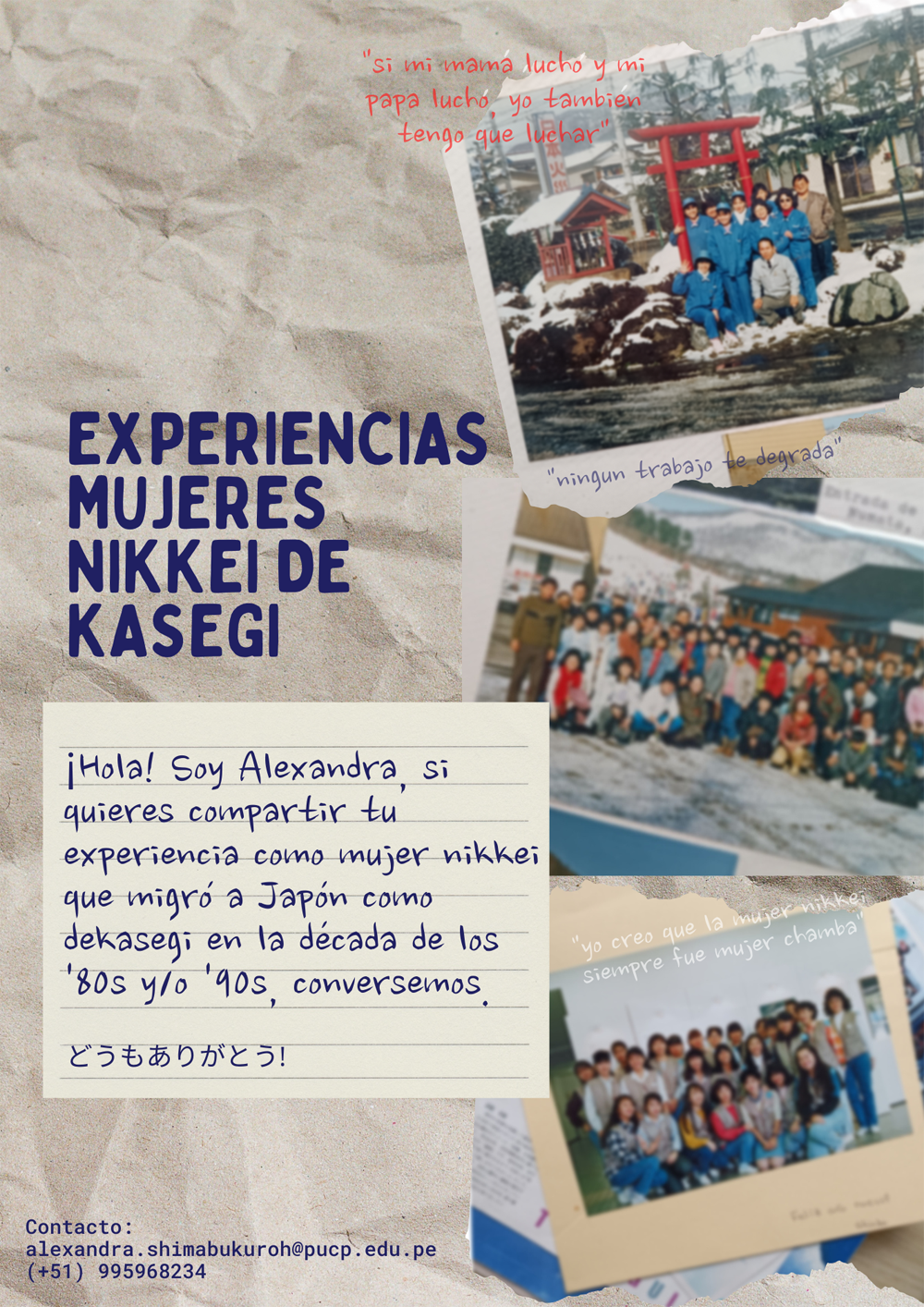

In Alexandra Shimabukuro's life, since she was little, dekasegi has been family, livelihood and stories. Now it is also a matter of research. The Sociology student at the Catholic University of Peru is preparing a thesis on the Nikkei women who migrated to Japan in the 1980s and 1990s.

“It is an experience that has always been in my family, and that I have always heard from a very young age at home,” says the young Yonsei.

He does not speak from hearsay, from a reference from some distant uncle or from readings. He has not experienced it firsthand, but it has had a nuclear impact on his life. His ojii was dekasegi (his remittances contributed to family support); his mother, too. He doesn't know much of his family in person because they are immigrants to Japan.

“The other time, before falling asleep, I thought: how much do I owe the dekasegi? If my parents hadn't had that, I probably wouldn't be studying at PUCP right now. Or it wouldn't exist, maybe,” he reflects.

IDENTITY BREAK

Alexandra wants to better understand the dekasegi phenomenon, cross the family framework and probe other lives. The hegemonic narrative focuses on the economic crisis of the 1980s to explain the mass migration of Peruvians to Japan, but it seeks to go further, exploring social or political factors behind a collective experience that fractured the Peruvian Nikkei community.

What strikes him most about the exdekasegi is the “break of identity”, their “misplacement”.

Misplaced in Peru, misplaced in Japan.

“The generations of my parents, of my ojii, my obaa, felt like... not so Peruvian. They told me: 'At school (in Peru) I didn't feel like a part of it, and when I went (to Japan) neither did I, because I was a foreigner.'

Her research on women is in its infancy, but she has already been able to detect certain common traits regarding identity.

“Maybe unconsciously they felt Japanese. They arrived in Japan, they saw that reality was very different, that they were foreigners (because they are), and there was a kind of rupture there, of 'now, who am I?', where do you belong. I see that a lot,” he says.

The dislocation of the generations before hers (nisei and sansei) is foreign to her, since she does not have to deal with identity conflicts. She is clear that she is Peruvian, not Japanese.

However, that does not mean that I conceive of identity in a monolithic way, without room for nuance or diversity.

“I don't know if I feel Peruvian exactly... Being Peruvian is very broad, I have more affiliation with particular groups, and sometimes those groups are globalizable. Sometimes I can feel a greater sense of belonging with an otaku group from a particular anime, and that comes from the Nikkei, the Peruvian, it can go to the Latin, to North American communities,” he says.

Or you may feel more affinity with, for example, Latin American women who face scourges such as violence.

“Being Peruvian sometimes seems very broad to me, obviously I am, but I feel that in my generation there is greater belonging to more specific groups; It comes out of geographical contours, they are globalized things, very dynamic,” he adds.

In the Nikkei bubble, although his generation is not marked by dislocations like its predecessors, it has witnessed backwardness more typical of the last century, when expressions such as “perujin” or “nihonjin” were common in the community.

Recently, during a meeting with Nikkei youth, someone referred to a friend as “perujin,” something that Alexandra found very strange. “I wanted to tell him 'but we are all Perujin', I don't understand,” he says.

The young Yonsei has socialized in Nikkei spaces, but also with other human groups. Being Nikkei is one of their identities. There is no single identity, he insists.

“I don't know what Nikkei identity is,” he admits. And if there is something specific that designates or defines it, he does not believe that it is immutable or absolute.

In any case, beyond what the Nikkei identity means, a sense of belonging unites it to the community, it has been one of its areas of socialization. “I feel comfortable, I feel it is part of me.”

Studying the dekasegi phenomenon will help you better understand its origins: “Where I come from, where my family comes from, what previous generations, particularly women, have done.”

For now, he has perceived a difference between the Nikkei who went to Japan to work and those who did not. “Dekasegi people claim to be Peruvian more,” he comments. Having collided with a country that opened their eyes (you are not nihonjin, but perujin), has pushed them to emphasize their Peruvianness.

On the other hand, those people who did not experience dekasegi still seem to feel more Japanese.

VOICE TO NIKKEI WOMEN

Alexandra Shimabukuro has decided to limit her research to Nikkei women who migrated to Japan and returned years later to Peru.

The student investigates the reality of young Sansei women who left for Japan, leaving a university degree halfway or barely graduating from school—girls still single with personal life projects—or women with families and therefore with other plans.

Through her work she hopes to give a voice to those who have not been sufficiently heard, to revalue Nikkei women, to transcend the traditional male gaze.

The study will also allow her to delve into the generational change that occurred when young dekasegi women—unlike their mothers or grandmothers, generally constrained to the domestic field—charted their own path, independent and free.

Progress has been made in bridging gender gaps. However, old practices that Alexandra has witnessed remain, such as meetings in which the men are seated while the women work in the kitchen preparing the dishes.

Now, his experience in this regard has been sui generis. “My ojii's case is very particular, because my ojii doesn't like to go out much. In my case, the one who did everything around the house was my ojii; My obaa loves to play gateball, sing with her friends, dance for the undokai, that kind of stuff. She was the one who picked me up from AELU, but my ojii was the one who washed my polo, the one who cooked my gohan, absolutely everything,” she says, with a smile that shows gratitude and affection.

© 2023 Enrique Higa Sakuda