“Quiet now, there is not a thing besides the low, humming sound of the body

In my mouth, chewing on the words

I cannot speak to them out loud until I’m ready….”From “Stone Between The Lips” by Brian Kobayakawa (aka Brava Kilo) and Annie Sumi

Like stepping into a time machine, Kintsugi takes its audience back more than 80 years in time when we lived on Paueru Gai (Powell Street), up and down BC’s west coast, suffering through the injustices of the dispossession and internment, then being banished, again, east of the Rockies after WWII or deported to Japan with the hope to rid BC of Japanese Canadians (JCs) forever more.

Reflecting on their own experiences as JCs, Gosei Annie Sumi and Sansei Brian Kobayakawa have created a remarkable multimedia presentation called Kintsugi, showing at Toronto’s Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre until March 17. Their EP of the same name, the first of its kind to describe the JC experience, is set to be released on March 10.

The self described ‘multi-racial’ musicians, collaborated on what at first appears to be a rather unassuming exhibit that is built around a vintage sewing machine. Participants are invited to push the machine’s foot treadle that sets their four-song cycle with their dream-like video images into magical motion. (Tip: if you hold the treadle down you don’t have to keep pumping.)

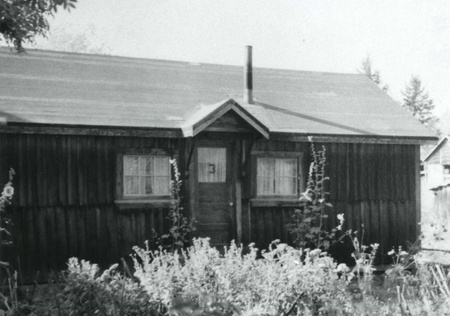

The narrative speaks to the story of how the descendants of these two musicians who lived through the internment survived through perseverance and resilience. The compelling visual presentation is an interplay of historical (e.g., video footage and cut up old letters written by the artists’ ancestors), modern and playful animated images created by the shadow puppeteers, Mind of a Snail, that interplay with the four-song cycle (“Stone Between Teeth,” “Chattels,” “Bronzo.” and “Kintsugi”). The projections incorporate present-day footage of two former WWII internment camp locations: Slocan City, where Kobayakawa’s father was born, and, the other, Rosebury, close to New Denver, where Sumi’s grandfather spent his youth.

Aptly named, Kintsugi pays homage to all internment survivors using this Japanese art form of putting together broken pieces to create something beautiful. Inviting us to peer through this time portal then, Annie and Brian take us on a journey to the past that will most certainly impact your own understanding of the internment experience.

As we continue to pick up the pieces of our ever-evolving Japanese Canadian community and identity, I can’t think of a more perfect metaphor to describe this process than Kintsugi.

* * * * *

Explaining how the exhibition came to be called Kintsugi, Annie says, “It was originally going to be called ‘tanuki’ to represent the shape-shifting qualities of being mixed-race, and the playful, mischievous, ‘trickster’ characteristics of the piece. When we gave the installation a deeper look, we realized that tanuki wasn’t really the core message of the piece—that is how we came to Kintsugi.”

Brian adds, “Kintsugi was initially the name of just one of the pieces of music for the installation, but as we examined it further, the metaphor of celebrating the beauty in the repair of something damaged felt so perfect for what we were trying to convey with the entire project that it became the name of the piece as a whole as well.”

“Bronzo” pays homage to some of the things that the community lost with internment: our haiku voice and our renowned boat building abilities. The song contains archival recordings of Sumi’s great grandfather Choichi Hando Sumi reading his haiku poetry, and percussion sounds were made on a boat built by Kobayakawa’s ancestors. Chattels features lyrics composed entirely from the Government of Canada’s correspondence during the Bird Commission with the artists’ ancestors listing the belongings that were auctioned off at a pittance without their consent during their internment.

Describing the first single, “Stone Between the Teeth,” released on January 24, Annie says:

“The verses have these evocative lyrics that help bring the listener closer to their senses. They attempt to emphasize the importance of focused, embodied attention when working with trauma, grief, and sadness. I like to think that other people can relate to the feeling of being unable to speak about hard things: ‘In my mouth, chewing on the words, I cannot speak to them out loud until I’m ready.’

“Brian and I worked this song out while we were in the studio having a writing retreat. It was a combination of lyrics and concepts that I had already been sitting with, and ideas that Brian had been ruminating on: ‘slowing down, remembering to walk lightly and low to the ground like you taught me.’ The original lyrics came from a dream of meeting our ancestors on a bridge in a place that resembled a Japanese garden, and being able to face that person and talk freely about where we come from, healing old wounds, and living with love.”

Brian recalls their first meeting at a conference called Folk Music Ontario in 2014.

“We stayed in touch, and followed each others’ careers for quite some time. The Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre initially commissioned Annie to compose some music for a concert, and I was chuffed when she asked me to partner in that.

“As the pandemic brought the plan for the concert to a halt, we pivoted towards what became this project. I have long been interested in sensors and installation art, and that—combined with a few songs started that we both really believed in–led us to creating this installation. A key moment in that process was when we acquired a substantial pile of documents, through Landscapes of Injustice (University of Victoria, BC), that helped to uncover information about both of our families’ internment experiences. Those documents revealed that the Singer sewing machine at the heart of the installation was one of the few possessions from pre-internment that remained with either family.”

Prior to this project, neither Annie nor Brian knew much about their family’s internment stories. Brian knew that his family had been in west Vancouver, and that his “Jichan” had been a boat-builder with his two brothers. “Internment stories weren’t really part of our family dialogue,” he continues, “My father was born in internment and doesn’t really have any memories of that.”

Recalling her own experience, Annie adds, “After briefly learning about the Japanese Canadian internment in elementary school, my parents told me a little bit about our family history, but I didn’t get many of the stories until I was much older. Before the internment, my Tohana family was based in Vancouver and my Sumi family had a thriving farming business on Mayne island. During the internment my Nana and her family were sent to Tashme, and my Papa’s family went to the Rosebery camp.”

As with all JCs who were forced “east of the Rockies” after WWII, racism followed the Kobayakawa family to Ontario. Brian remembers growing up in Markham, north of Toronto, where they were one of only a few Japanese Canadian families.

“Racism was rampant in the form of schoolyard bullying and slurs in my direction. It’s hard to measure the impact of that. More noticeable to me is how moved I feel now seeing more Asians in the arts, on TV, in movies—that wasn’t as prevalent then. I realize now how certain music and film and art that resonated with me was because there was a person of colour involved in it, when at the time I was unaware of how much of an impact that had.”

Annie dealt with racist comments in elementary school, by saying “‘my Papa is a Japanese samurai so you better not call me names!’ Being mixed race sheltered me, in some ways, from racist remarks and prejudice. I think I used my perceived whiteness as a survival mechanism, and it has taken this long to reclaim my Japanese identity and celebrate the parts of my ancestry that were discouraged after internment.”

So, in the discussion about self identification, Annie and Brian have chosen “mixed race” as the preferred label. “We actually were using Hapa initially when we started this project,” recalls Brian, “Until I became aware that to Hawaiian Hapa people, this was a word reserved for people there. I do think of myself as Asian, as well as Caucasian and mixed-race. Annie and I both have Caucasian mothers, and to us, the experience of being mixed-race is true to us, and different than what we assume the experience of being full-blooded Japanese Canadian would be.”

Both Annie and Brian came to “Kintsugi” as accomplished musicians: Brian, aka Brava Kilo, is a composer, bassist and synthesist from Toronto. He’s a member of The Creaking Tree String Quartet; he’s released four albums; won four Canadian Folk Music Awards and was nominated for four JUNO Awards. He’s a busy session bassist, having played on over 100 albums. He tours extensively with singer songwriter Serena Ryder as music director and bassist. In 2018, he launched his own solo career as Brava Kilo. He’s also created his first film score for Jackals & Fireflies directed by Oscar-winner Charlie Kaufman.

Annie is a songwriter and vocalist who “takes inspiration from the vast, Canadian landscapes, and the collective human experience.” She has released three albums, toured across North America and Europe, and received nominations from the Canadian Folk Music Awards and Toronto Independent Music Association. Her recent album, “Solastalgia,” reflects on environmental decline and the journey towards understanding our place “in the family of things.”

Talking about their collaborative process, Brian says:

“We collaborated in many different ways—what began with meeting up to do research and discuss our feelings around these topics led to sessions of creativity, often buoyed by a piece that one of us brought from an individual creative session. During our creation process, Annie moved to the US, leading to a more remote form of working, sending files and snippets of ideas back and forth. I can’t help but use musical collage as part of how I work, where I superimpose elements from disparate sessions onto one another to create something new.

“After all that, we did get together in the studio for several days where we really worked out the bones of each of these four songs, finalizing lyrics and chords, as well as arrangements and sonic elements. We had our families join at the end of those sessions, which was very fun and emotional and powerful, and it allowed us to have members of our families contribute to the music directly.”

Explaining a line from their press release: “The imposed silence of internment trauma. Directly confronting the experience of reorienting in a post-internment Canada”.

Brian says it’s about reorienting the internment experience in 2023:

“I think for us it’s important to keep the conversation alive, as we’re doing here. Internment is a big, heavy part of the experience for all Japanese Canadians whose families were here at that time, and I can’t attempt to say that the ways we choose to confront it today are going to be something that would necessarily work for another family. For Annie and I, opening the conversation at all in 2023 was a big leap, given the ways in which our families have chosen to speak around rather than about it, and something we did with the utmost care.

“Systemic racism still surrounds us constantly, in this colonial system we call Canada, and the impacts of that are felt by so many different communities. Creating art based on the experiences closest to us is a natural form of activism; and for Annie and I, creating a space to confront these feelings and openly discuss them feels like the most healing maneuver we could muster, and one that while specific to Japanese Canadians, could be a point of introspection for any family, community or individual who deals with oppression of any kind.”

Annie says that, from her perspective, “reorient(ation) in a post-internment Canada” expresses a desire to encourage our communities to talk about experiences related to any aspect of their identity (i.e. race, sexual orientation, gender, etc.) that has been traumatic, or left a lasting, negative imprint on their lives.

“One of the hardest parts of this project has been recognizing the way that silence speaks and perpetuates trauma—acknowledging the source of our angry, distrustful, and addictive behaviours creates opportunities to break from cycles of struggle, and create new, generative patterns of embracing ourselves and our identities.”

When asked about what kind of Japanese Canadian community they envision for the future, Brian talks about the impact of attending GEI: Arts Symposium in September 2022 in Victoria, BC:

“I was invigorated by meeting so many JC artists. It was deeply moving to feel the strength, artistry, joy, empathy, and passion in that community. I hope for more connection around art, food, Japanese Canadian traditions, and supporting each other as we navigate our role in the greater community.”

Recalling that transformative experience, he continues:

“Listening to some of the elders’ stories about their experiences with internment and racism, in the industry of their craft, in activism work, and more, left a lasting impression on me. I particularly enjoyed poet/writer Joy Kogawa’s emphasis on ‘Love’ and the power of love; it invited me to remember the way I approach my own art, and the way I approach community. After the symposium, I took the time to look up many of the artists I met that weekend and I was so inspired by their work, ethic, and commitment to resisting systems of oppression.”

Plans are underway to present Kintsugi across Canada.

For more information:

- Japanese Canadian Cultural Center: Exhibition Kintsugi.

- Instagram: @bravakilo and @universeofannie

- Website: Brava Kilo | Annie Sumi

© 2023 Norm Masaji Ibuki