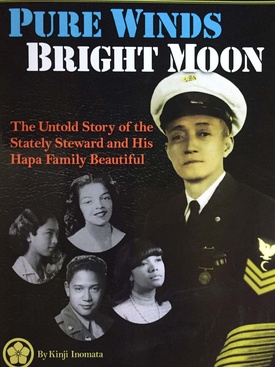

If ever there was an award offered for the most remarkable Japanese American family saga, one formidable contender would be that of the Inomata clan, as revealed in the book Pure Winds, Bright Moon, by Kinji Inomata, as well as supplementary documents. Their history defies simple-minded ideas about Japanese Americans, their lives, and their interactions with other groups.

The family story starts with a Japanese boy named Kenji Inomata. He was born in 1885 in Kashiwazaki, Niigata, Japan, the son of Tuna Kuga-Inomata and Usuke Inomata. Kenji’s father died suddenly while on a trip in 1895, and the ten year-old boy was sent to work with an uncle.

Soon after, Kenji was befriended by an English ship captain. He taught the captain Japanese, in exchange for the captain’s instructing him in English. Kenji stowed away on the captain’s ship, on which he ultimately found work as a cabin boy.

After sailing to many ports, at some point in time circa 1900 Kenji’s ship sailed into New York Harbor. There Kenji jumped ship, swam to shore, and settled illegally in the United States.

Kenji apparently spent the next years in New York. In 1906, he was recorded as working as a waiter and living in Sands Street, near the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Learning that the U.S. Navy was in search of stewards, in December of that year Kenji enlisted as a 3rd Class Mess Attendant. The naval enlistment officer somehow reversed his name on his papers and registered him as Inomata Kingi, which henceforth became his official name.

Over the next five years, Kingi served on the U.S.S. Indiana, where his tours of duty took him to ports around the world (including Port Said, Egypt, from which he took a trip to the pyramids). He thereafter served on the battleships U.S.S. New Jersey and U.S.S. Maine and the cruiser U.S.S North Carolina.

In 1916, Kingi was posted to the Navy Aeronautic Station at Pensacola, Florida. He would remain there for 21 years on aviation shore duty. During this time, he rose through the ranks, attaining the positions of Steward to Commandant and then Officer Steward, First Class, and serving under Admirals and other commanding officers. For a stretch of some years, he worked as personal steward to the Naval Station commandant, Captain Harley Hannibal Christy, a World War I war hero. (In those years he also met Wallis Simpson, the future Duchess of Windsor, who was then married to a navy pilot).

During the years that Kingi was stationed at the Pensacola Naval Air Station, he resided in the surrounding area. In 1918, he married Genevieve Beckham, a native-born Southerner of mixed black and white (and possibly Native) ancestry. Her son Albert came to live with the family. In the ten years that followed, the couple had six children together (a seventh followed years later).

In January 1919, Kingi and another Issei WWI veteran, Kagemichi Sako, applied for US citizenship in the United States District Court of the Northern District of Florida. Although Japanese were formally barred from citizenship under the 1790 Immigration Act, Kingi and Sako argued for naturalization on the basis of the Congressional Act of May 9, 1918, which offered access to citizenship to all aliens who had served in the US military and had been honorably discharged. (Not wishing to risk the citizenship of his new wife, who faced losing hers for marrying an alien, or attracting official hostility due to their interracial marriage, Kingi declared himself as single in his petition). Captain Christy dispatched two ensigns to the court as witnesses attesting that Petty Officer Kingi was a “gold striper” of exemplary military behavior and good moral character.

Faced with such powerful backing from naval officials, Judge William Bostwick Sheppard granted Kingi and Sako their citizenship. New Orleans Naturalization Examiner J.C. Kellett protested the ruling, but his objections were overruled by Judge Sheppard. (The U.S. Supreme Court subsequently decided in the 1922 Ozawa case that Japanese aliens were ineligible for citizenship, leading to removal from citizenship rolls of a mass of Japanese aliens who had naturalized. Kingi’s citizenship, once acquired, was never rescinded. Still, it was not until Congress passed the Lea-Nye Act of 1935 that Asian American World War I veterans became statutorily eligible for naturalization).

In 1927, Kingi was transferred from active duty to the Naval Reserve. As an interracial couple, the family faced limited employment prospects and racist hostility in Jim Crow Florida. While Kingi kept his Pensacola residence for official purposes, the family moved to Los Angeles in 1928. At first, the Kingi family faced prejudice from local Nikkei due to its mixed-race identity. The proprietors of a hotel in Little Tokyo even ejected the Kingis (With seven young children, the noise they made might also have been a contributing factor). Eventually they bought a home near Wrigley Field in South Central Los Angeles.

During the first decade after they arrived in Los Angeles, the Kingis also lived a fairly precarious existence in financial terms. Inomata Kingi worked for a time as a valet to singer/actor Al Jolson, then was engaged as a steward/handyman in an apartment house. He also did odd jobs—the 1930 census listed Kingi as a janitor at an optometrist’s office.

In 1937, following his retirement from the navy, Kingi was hired as a janitor by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. He thereby became the first Issei employee of the Department, which was notorious for refusing to hire Asians. His eldest son Inomata Kingi Jr. found a job as a civilian mechanic’s helper at McClellan Air Force Base. Between their two salaries, the family economy improved. Kingi bought a larger house on East 43rd Street from a Mexican rancher.

Despite ambient racial hostility, members of the younger generation worked to establish themselves within Los Angeles’s multicultural urban life, including among Japanese Americans. Ceclia Tase Kingi, the family’s only daughter, was a popular student at Jefferson High School, and was selected for the elite Ephebian Society. Her social activities with the Nisei social club Kalifans were recorded in the Nisei press.

In 1939, following graduation from high school, Tase married Willis Louie, a jazz saxophonist of Chinese and West Indian ancestry. Inomata Jr., the family’s eldest son, met and married Augustina (Tina) Andrade, a Bakersfield native of Cape Verdean and Cuban extraction. Masao Henry Kingi married his high school sweetheart, Henrietta (Henny) Dunn, a Chicago-born African American. All three marriages were recorded in Rafu Shimpo.

In early 1942, in the wake of Pearl Harbor and U.S. entry into the Pacific War, Inomata Kingi, Sr. was fired from his job on racial grounds. Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron pressured all Japanese American city employees to “voluntarily” request leaves of absence or retirement as a means of dismissing them without falling afoul of civil service rules. Inomata, Jr. was also dismissed from his job.

The loss of employment brought on hardship for the Kingi family. They were soon to face even more threatening prospects. In early March 1942, once the U.S army issued orders excluding Japanese Americans from the West Coast, military police ordered Inomata Kingi, Sr. to report to the Civil Control station for “evacuation.” Kingi, Jr. took action to avert removal. Taking a photo of his father in navy uniform and a photostat of a letter of commendation from Secretary of the Navy Claude Swanson, he showed it to relocation officials, who promised to look into giving him an exemption.

Kingi Jr. meanwhile solicited the aid of George W. Burleson, adjutant of the Colored American Legion post on Central Avenue. Kingi, Jr. drafted a letter to Western Defense commander John DeWitt, sent under Burleson’s signature, requesting that the Kingi family be exempted from “evacuation” because of their mixed marriages. Burleson affirmed that the Kingis lived as non-Japanese and were not members of any Japanese community. Such distance demonstrated their lack of threat to national security, as well as their fitness for civil service jobs. A week later, Assistant Adjutant General R.P. Bronson responded on DeWitt’s behalf, dismissing such arguments as absurd.

In the end, the family applied to the Department of Justice for exemption. Sometime in early Spring 1942, Kingi and his family went for an interview with Justice Department officials at the Federal Building in Los Angeles (seeing the multiethnic family, a Justice Department official joked that Kingi had brought the League of Nations with him!) The family petitioned U.S. Attorney William Fleet Palmer for exemption due to Kingi’s long military service and naturalized U.S. citizenship. As with his naturalization petition, Kingi provided affidavits from Harley Christy, (by then elevated to the rank of Vice Admiral) and other naval officials.

Following the hearing, Kingi was investigated by the FBI and the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI). When the ONI agents arrived at his house to interview him, Kingi thought he was being arrested and refused cooperation. The agents managed to convince him of their good intentions, and he admitted two unarmed men, who interviewed him in his living room.

In April 1942, the U.S. Attorney’s office granted the petition for exemption, and issued permits for them to remain on the West Coast. The Kingi family were the only West Coast Japanese Americans thereby exempted. (Palmer had awarded an exemption to another World War I Navy veteran, Nisuke Mitsumori, shortly before, but DeWitt proceeded to overrule all existing exemptions in his third curfew order).

Yet, even if Inomata Kingi was exempted by the Justice Department, whether the Western Defense Command would recognize that exemption was unclear, as was the status of the Kingi children. In the end, the family members were issued official certificates (and laminated ID cards) under the Army’s exemption policy for mixed-race people and interracial couples—even though their case diverged from the strict terms of the policy. Indeed, despite the Army’s rebuff to Inomata Jr. and George Burleson’s argument to spare the family because of its mixed-race nature, it is an open question whether that argument may subsequently have led the army to develop the notorious policy.

Even though the Kingis were exempted from mass removal in mid-1942, the younger members of the family faced bullying at school and race-based persecution by anti-Japanese gangs. The family also experienced economic hardship, until father and son found work as shipping clerks. In the last year of the war, Inomata, Jr. became active with the Catholic Interracial Council to help shape public opinion to support camp inmates returning to the coast—notably Esther Takei, whose admission to Pasadena Junior College was opposed by anti-Japanese bigots.

Inomata Kingi retired in 1948. In later years he lived with different family members. A 1967 document lists him as residing in Washington DC. He died in 1974, shortly after his wife passed away.

Inomata Kingi’s descendants1 entered multiple fields of endeavor. Following in their father’s footsteps, several family members joined the military, including son Masao. Another was performing. Masao’s son Henry Kingi become a legendary Hollywood stuntman and actor, and his son Henry Kingi, Jr. also worked as a stuntman and assistant director. Together with his wife Lindsay Wagner (star of the 1970s television series The Bionic Woman), Henry Kingi, Sr. had two other sons, Dorian Kingi and Alexander (Alex) Kingi. Both Dorian and Alex have become stuntmen like their father, and have also worked as actors and directors.

Because they were exempted from mass removal, the Kingis were initially excluded from redress under the 1988 Civil Liberties Act. However, multiple family members launched an appeal, and were ultimately awarded redress payments. In spite of having escaped going to camp, the family (including its non-Japanese members) endured financial hardship and discrimination as a result of Executive Order 9066. Despite its unique features, the Kingi family’s story stands as an exemplary Japanese American narrative.

Note:

1. Read a story of Kingi’s grandson, Ricardo Jiro Kingi, on Discover Nikkei.

© 2023 Greg Robinson