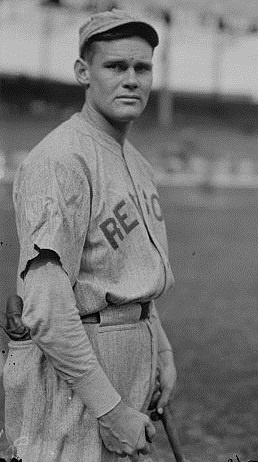

“Dutch” Leonard is no longer a household name, but he left behind an enduring reputation in baseball history. Originally born in Birmingham, Ohio and raised in Fresno, California, Hubert Benjamin Leonard became one of the greatest pitchers in baseball as a left-handed pitcher for the Boston Red Sox. In 1914, he achieved the modern-era record for lowest single-season earned run average (ERA) of all time at 0.96 – a record that he still holds to this day. He led the Red Sox to World Series championships twice, first against the Philadelphia Phillies in 1915, and then the following year against the Brooklyn Robins (ancestors of today’s Los Angeles Dodgers).While with the Red Sox, Leonard became Babe Ruth's drinking buddy shortly before Ruth was traded to the Yankees.

He later played with the Detroit Tigers for a total of 4 seasons, where his famous feud with Tigers star player and manager Ty Cobb reached a fever pitch. After the 1925 season, Leonard accused Cobb and another star player, Tris Speaker, of “fixing” games with gamblers. Cobb responded by charging that Leonard was a Bolshevik. The feud resulted in Leonard’s departure from baseball, and he moved back to Fresno where he opened a vineyard in nearby Sanger.

Although Leonard’s career as a ballplayer is worth remembering, equally admirable is his defense of Japanese Americans after World War II - often in the face of domestic terrorism.

After Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, the city of Fresno, which thousands of Japanese American men, women, and children called home, was emptied of its Japanese American community. After removing the local population from their homes, the Army opened a temporary assembly center on the Fresno fairgrounds, where five thousand Japanese Americans awaited shipment to concentration camps in Arkansas and Arizona.

In December 1944, just before the Supreme Court ruled in Ex Parte Endo that the government could not indefinitely hold Japanese Americans, the army lifted exclusion. Japanese Americans families then began to return to their former homes in California. They soon faced discrimination and threats of violence all over the state.

In Fresno, cases of discrimination were particularly acute. Mayor Z.S. Leymel declared in December 1944 that the arrival of Japanese Americans to Fresno would create “a headache” for the city. In the nearby towns of Reedley, Selma, and Orosi, locals shot at the homes of several Japanese American families. In Selma, locals burned down the home of returning incarceree Robert Morishige. On January 22, 1945, a group of ranchers in Orosi gave an ultimatum to the city’s Japanese American families to leave the city by the end of the month. The deadline passed with no incidents reported.

Local readers sent vitriolic letters to the editor of the Fresno Bee calling for the government to keep Japanese Americans out of California. In one headline from April 9, 1945, the Bee proclaimed “Japanese return is seen as threat to coast security.” The nastiness of the commentary provoked several letters to the editor in defense of Japanese Americans, most of which cited the record of the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes expressed outrage at California state officials for sitting on their hands.

Government officials also responded negatively to the return of Japanese Americans. The Fresno County branch of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration withheld benefits from Japanese Americans who did not furnish proof of renouncing dual citizenship. The County Board of Supervisors refused to provide welfare funds for families, and local prosecutors refused to evict families who occupied the former homes of Japanese Americans. One official proposed reusing the Fresno County Fairgrounds – the former site of the Fresno Assembly Center – as temporary housing.

Dutch Leonard, however, responded with compassion. Even before Japanese American farmers were taken away to camp, Leonard feared that his neighbors would lose their farms to unscrupulous buyers in the days before forced removal. Leonard offered to manage the farms in their absence and promised to pay them a percentage of the proceeds of the harvest. After the Army lifted the West Coast exclusion ban and the farmers returned, Leonard proved true to his word. He handed back the land intact and paid the Japanese Americans farmers $20,000 in profits accrued during their imprisonment.

Meanwhile, Leonard contacted all the camps to offer jobs on his vineyard to Japanese American men and housing for their families. Leonard’s brother and business partner, Edward H. Leonard, travelled to Manzanar, Gila River, and Poston to recruit workers. War Relocation Authority Director Dillon Myer met with Dutch Leonard about his proposal, and described him as “a friend of the evacuee” who stood for the principles of the WRA. Several groups from Poston, Rohwer, and Amache accepted jobs on the farm, and by June 1945 the Leonard Bros. employed over 300 Japanese Americans, to whom he paid eighty cents an hour, supplied free housing, and paid a harvest bonus.Several individuals, including former Yankee pitcher and civil rights activist Harry Kingman, praised Leonard for his courageous deeds. Kingman, the director of the West Coast Fair Employment Practice Commission, worked alongside civil rights leaders such as NAACP lobbyist Clarence Mitchell Jr. to combat racial discrimination on the West Coast. The Pacific Citizen applauded Leonard’s efforts in the face of several incidents of domestic terrorism. In Bradford Smith’s 1948 study Americans from Japan, Smith states: “First to employ Japanese, even before V-J Day, was “Dutch” Leonard, former baseball star and owner of 1600 acres of vineyard near Sanger.”

Leonard was not the only Major Leaguer to hire Japanese American resettlers. Former Washington Senator’s outfielder Sam Rice famously hired a Japanese American family to work on his Maryland poultry farm in 1943. Rice and his neighbor, Secretary of Interior Ickes, both hired Japanese Americans as a way to promote the WRA’s resettlement program.

In the years following the war, Leonard maintained a friendly relationship with Fresno’s Japanese American community. Poet Lawson Inada recalls from his youth of speaking with baseball legend Kenichi Zenimura about Dutch Leonard and his vineyard in Sanger. It is rumored that Zenimura drove workers from their homes to Leonard's vineyards using a surplus World War I army ambulance. A fanatical lover of music, Leonard hired Maybelle Nakamura of Sanger to catalogue and file his catalogue of 24,000 classical music tapes. Sadly, on July 11, 1952, Dutch Leonard died of a sudden stroke. One of his last pictures shows Leonard together with Nakamura in his study.

Dutch Leonard’s story serves as one of the few profiles in courage during a sad chapter in California’s history. Alongside Sacramento’s Bob Fletcher, Leonard remained true to the principles of equality at a time when many chose to harm, rather than help, Japanese Americans. His heroism should be remembered.

© 2023 Jonathan van Harmelen