In my efforts to learn about Nisei soldier history, I inevitably began to learn more about the incarceration of the Mainland Nikkei during World War II. As we know, every Nikkei was forcibly evacuated from the West Coast states and put into camps. Exploring their story, I learned about the over 2,000 Japanese Latin Americans (JLA), mostly from Peru, who were rounded up by their own governments, transferred to the U.S. and put into camps.

A remarkable part of this story is seen through the person of Seiichi Higashide who, along with his family, was uprooted from Peru during World War II and incarcerated for two years on the U.S. mainland, eventually making a life for himself in Hawai‘i. An earlier article on the Higashide family story written by Gary Tachiyama was published in the March 20, 1981, issue of The Hawai`i Herald.

Higashide published a memoir in Japanese in 1981. His daughter Elsa Kudo and his son-in-law Eigo Kudo had it translated into English and published by the University of Washington Press. The following borrows from the book’s second English edition, Adios to Tears: The Memoirs of a Japanese-Peruvian Internee in U.S. Concentration Camps.

* * * * *

Early Life in Japan

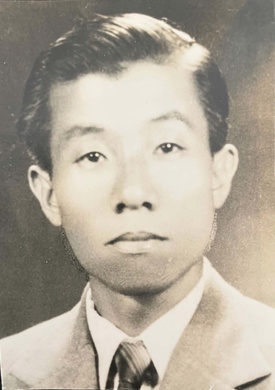

Seiichi Higashide was born in 1909 in a remote farming village in Japan’s northernmost island, Hokkaido. Farm work was demanding and winters were harsh. He found his way to Tökyö, where he toiled at menial jobs during the day and studied architecture at night. Seiichi later wrote that growing up he lived a life of “quiet discontent.” Believing his opportunities were limited, he decided to emigrate.

A New Beginning in Peru

Because the United States had closed its borders to Asians through the 1924 Asian Exclusion Act, Seiichi’s focus turned to Peru. With the financial assistance of his technical school classmates and faculty, he sailed to his new land. He was 21.

After an initial period of adjusting to the culture, environment and the challenges of the language barrier, he married a Peruvian Nisei (a second-generation Nikkei), Angelica Yoshinaga. With her help, he started a budding retail business. He not only succeeded but emerged as a leader in the Nikkei community of Peru, eventually to his detriment. Five children followed in quick succession: Elsa, Carlos, Irma, Arthur and Martha.

The Dark Clouds of War

Shortly after the war in December 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Thursday, Feb. 19, 1942. This order empowered the U.S. Army’s Western Defense Command to remove the Nikkei community from the West Coast of the U.S. The internment program was administered by the War Relocation Authority, which operated ten inland camps, supervised by civilian leaders. The camps were designated military areas and guarded by military police.

While not in a war zone, Peru was not immune from the impulses that drove E.O. 9066. The U.S. issued a “Proclaimed List of Certain Blocked Nationals,” and as a Nikkei community leader, Seiichi’s name appeared on the list. In January 1944 he was arrested by four Peruvian policemen. Ten days later, he was put on a ship by Peruvian police and American soldiers. Detained in Panama with fellow deportees, he was put to work without compensation for several months.

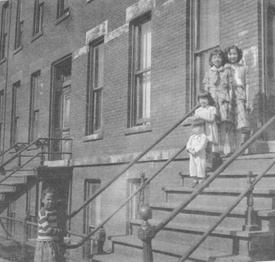

When he learned that families could be reunited, he contacted Angelica asking her to join him. She closed out their business operations and got the five children ready for travel. In addition to the WRA, other camps were operated by the Department of Justice and Immigration and Naturalization Service. One such facility was the Crystal City Family Internment Camp in southern Texas, set up to accommodate international internees with families. The Higashides were reunited at Crystal City in July 1944. The children were placed in school and recreational activities. Thus began the Americanization of the Higashide family.

War Ends

They were subsequently allowed to leave Crystal City on the condition that they move to a place called Seabrook Farms in New Jersey, a packing plant that provided steady but low-wage work to many people of Japanese ancestry. For the JLAs, their records either had been lost or destroyed. Having no documentation of entering the United States, they were essentially stateless — literally people without citizenship in a country. Only a few among this population were repatriated to Japan, and Peru refused to take them back.

The U.S. government designated those who stayed “illegal aliens on conditional release.” It was like a form of parole with the specter of deportation hanging over their heads. From this tenuous position, Seiichi nonetheless managed to relocate his family to Chicago, where they encountered racial discrimination in housing and employment practices.

Again working at menial jobs that didn’t require English proficiency, he and Angelica scraped together enough money over many years to acquire several apartment buildings, which provided a stable livelihood for their family. Three more children were born as U.S. citizens, Richard, Deanna, and Mark, for a total of eight. In 1958, Seiichi and Angelica became naturalized U.S. citizens.

Migration to Hawai‘i

In 1971, then 62 years old, Seiichi pondered retirement with thoughts of escaping Chicago’s cold weather. He and Angelica looked at potentially suitable places, including Japan, but made no decision. In 1973 Angelica developed severe neuralgia—which creates a sharp, shocking pain, like shingles, and is due to irritation or damage to the nerve. On the advice of their doctor, they took a vacation in Hawai‘i, visiting son Arthur, who earlier had relocated for health reasons.

Angelica responded well to the warm weather and was soon able to take walks on the beach. After an extended visit, they decided to make Hawai‘i their retirement home. One by one, all eight Higashide siblings decided to join them in Hawai‘i.

As with all their previous journeys, this latest move was not without its challenges. Hawai‘i’s high cost of living was a hurdle but Seiichi and Angelica adjusted. Being thought of as “kotonks,” or Mainlanders, was a new form of prejudice. As “outsiders,” the children encountered challenges in finding jobs but over time found meaningful employment opportunities, not only surviving but thriving. Refusing to feel angry or frustrated, Seiichi assigned this form of discrimination to a natural closeness of people in an island community.

(Note: In a previous article, I discussed how the term “kotonk” originated when Hawai‘i Nisei soldiers encountered cultural and language differences with the Mainland Nisei in the all-Japanese 442nd Regimental Combat Team and coined the phrase.)

Pursuit of Justice for Japanese Latin Americans

In retirement, Seiichi became a leader in the redress movement for the JLAs who had been incarcerated during the war. He wrote letters to Congress and other government executives, including President Ronald Reagan. At the age of 72, he testified to the U.S. Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians at a hearing in Chicago. His son-in-law Eigo interpreted his testimony into English and also testified because his family was also Peruvian and had been incarcerated. Daughter Elsa also testified. She recalls that the entire room fell silent when Seiichi spoke with such force and sincerity and because no one previously had heard of the plight of a Japanese Latin American.

Despite the obvious wrong, the apology and symbolic $20,000 payment conveyed by the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 did not include JLAs. However, due in part to the Higashides’ testimony, the Redress Commission’s report “Personal Justice Denied” documented their experience. Thereafter, the law was amended in 1992 to include JLAs who had remained in the U.S. and had been awarded permanent residency retroactive to their date of entry, along with their children born in the camps during the war. One hundred eighty-nine JLAs received the same compensation as Japanese Americans. Nonetheless, this amendment left a large majority of the JLAs out of the redress process.

In 1996, a class action lawsuit was filed on their behalf seeking equal redress for the remainder of the affected group. According to the terms of a settlement in 1998, the DOJ offered a Presidential Letter of Apology to each eligible JLA internee, along with a token payment of $5,000. Over 700 internees filed for compensation under the settlement, while others refused it and continued to pursue the $20,000 figure.

Three Motherlands

Over his long lifetime, Seiichi worked out his complicated feelings for what he called his “three motherlands.” His first was Japan, which he remembered affectionately even with all the hardships he endured. His second was Peru, which he remembered positively even after his ill treatment and loss of property. His third was the United States, and despite his family’s incarceration during the war, he was proud of his American citizenship. He retained a deep affection for all three countries for the remainder of his life.

He wrote that in Hawai‘i he found his “paradise on earth.” He lived out his life with Angelica in a Waikïkï condominium. He died in 1997 at the age of 88, and Angelica passed away in 2012 at 95.

Seiichi expressed his feelings for Hawaiian culture in the last paragraph of Adios to Tears.

“I have heard that ‘Aloha’ basically means ’love’ but it differs from the Christian meaning of ‘love.’ Here, the term seems to be more directly connected to the earth that sustains us and to acceptance of human emotions. In that sense, ‘Aloha’ includes everything that I have sought for over many years.”

In reading about Seiichi Higashide’s remarkable life, I am amazed that he harbored no bitterness. Elsa Kudo recalls that neither he nor her mother expressed resentment at their uprooting and incarceration. It is a remarkable example of how the Japanese cultural values of kachikan or gaman (quiet endurance) and ganbari (persistence) can provide one with the ability to overcome difficulties in life. These values were embedded in Seiichi at an early age and served him well throughout his life.

In the preface to the second English edition of Adios to Tears, Elsa Kudo wrote:

“The JLA’s redress fight continues under the most trying circumstances. We hope it will end in victory. Our country will have shown true greatness to the world, and these almost forgotten [incarcerees] can finally have a sense of closure. All peoples in the United States of America will be able to feel secure that the concentration camps cannot be so easily duplicated in the future … better still, that such denial of justice will never happen again to anyone.”

Seiichi’s life story and Elsa’s words provide inspiration to take up the cause of justice for those racial or ethnic minorities who experience discrimination based solely on their differences.

* * * * *

Adios to Tears is available for purchase online. For more information on the JLA incarceration, you can visit the Densho Encyclopedia.

*This article was originally published in The Hawai'i Herald on February 17, 2023.

© 2023 Byrnes Yamashita