Izumi first learned about the Japanese American incarceration experience in 1984:

“I saw the NHK TV drama titled Sanga Moyu, a drama based on Toyoko Yamazaki’s novel, Futatsu no Sokoku. The story was about a Japanese American family, and in the story, one brother joined the US Army and his younger brother joined the Japanese Army. The family in the US had to go to Manzanar. I didn’t know about the Canadian internment/incarceration, until I read Toyo Takata’s Nikkei Legacy and Joy Kogawa’s Obasan after I started studying Japanese Canadian history.”

It took Izumi some time to understand the scale of the losses that Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians had to bear, she continues:

“As a Japanese, I grew up reading a lot of stories about people’s experiences during World War II, like The Diary of Anne Frank, Barefoot Gen, and Neko wa Ikite Iru (The Cats Survive), which is a story about the 3.9 Tokyo Air Raid that killed over 80,000 people in one night. I also read books about Korean children during World War II and children in the Vietnam War. So, in a way, the stories about children in Asia and Europe, where the war was actually fought, have a more direct impact when you read them.

“It is more difficult to understand how the uprooting and losses impacted, for example, Naomi Nakane in Obasan, because the story is about you being alive but having your very existence delegitimized. It’s not like, a bomb falls on your head and you’re burnt alive or blasted into pieces, but you’re told that you shouldn’t exist as who you are because being a ‘Japanese’ is a bad thing. They are both about a child’s death, but of a different kind.”

When asked about the internment/incarceration options that both the Canadian and US governments had in 1942, Izumi elaborated on how they worked:

“They could have left their ethnic Japanese population alone, because they were under strict governmental surveillance since before the war anyway. If they were given the chance, Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians would have worked extra hard with other Americans and Canadians for their respective governments’ war effort. The fact that so many Nisei volunteered for the 442nd Infantry Regiment, even when their family members were confined in concentration camps, shows that they were eager to cooperate with their native countries and to prove their loyalty.

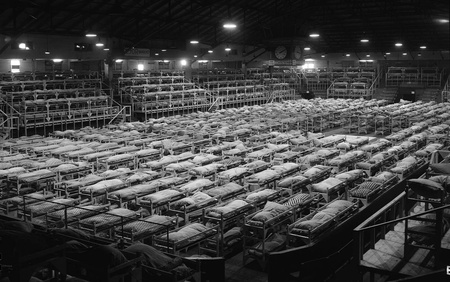

“The main difference between the JA and JC internment/incarceration was that the US government had the money and human resources to spare on the removal and confinement of Japanese Americans in concentration camps, while the Canadian government did not. The US Army was in charge of the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast into the Assembly Centers, and the Army personnel were dispatched to guard the War Relocation Centers.

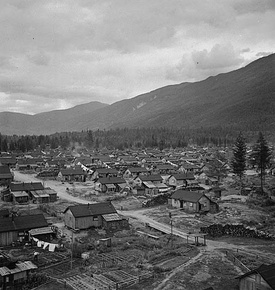

“The Canadian military refused to send their soldiers to remove Japanese Canadians from their homes, and confine them in Hastings Park (Vancouver) or in the British Columbia interior internment camps, because they simply did not have human resources to spare for the task. That is why the Canadian government had to create the British Columbia Security Commission (BCSC), administered by a Vancouver businessman, Austin Taylor, John Shiirras of the BC Provincial Police, and Frederick Mead of the RCMP (after whom Tashme, in a spectacular act of vainglory, was named: author’s comment).

“The Canadian government forced Japanese Canadians to pay for their own relocation and internment/incarceration. This did not happen in the United States. The Custodian of Enemy Property, created to keep Japanese Canadians’ property in protective custody, disposed of all of the property during the war without the owners’ consent and sold them for a very cheap price to war veterans and other non-Japanese Canadians. They sent a cheque to Japanese Canadians in the camps after deducting the costs of their removal and internment/incarceration. Most Japanese Canadians lost everything because of this dispossession policy and had to rebuild their lives from scratch after the war.”

Other stark differences between the JC and JA experience: The Canadian government did not lift its exclusion order until April 1, 1949, while in the United States, Japanese Americans were allowed back on the West Coast after December 17, 1944. Many Japanese Americans had already relocated and settled in the Midwest regions or the East, but many others returned to the West Coast after the war.

In Canada, fishers in Steveston re-established their livelihood back home relatively soon after 1949, as some canneries invited them back to restore their thriving industry and they needed Japanese Canadian fishers for that; but most other Japanese Canadians had already established their livelihood outside British Columbia, like the Ibuki family in Manitoba, and had no property to come back to on the West Coast. The dispersal policy was more thorough in Canada than the United States.

Even though it is somewhat well known that the governments of both Canada and the US got advice from senior military people saying the JAs and JCs were not a national security threat, they chose to ignore that advice.

Izumi continues: “It seems that the removal of the ethnic Japanese in both countries was politically motivated rather than based on objective military necessity. Since the prewar period, both Canada and the United States had politicians on the West Coast who gained popularity with their anti-Asian political agendas. Arousing anti-Asian sentiment was a political weapon those parties used to secure the support from their constituents. Such a political structure was generated by the fact that whites succeeded in monopolizing the political power in both Canada and the US by excluding non-whites from voting rights and/or citizenship rights.”

She speculates, just as I do, “that the war against Japan gave a perfect excuse for anti-Asian racists to expel and steal from Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians, who were playing important roles in certain economic sectors, such as agriculture and fishing, on the West Coast. Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians were politically vulnerable when they were targeted, because in the United States, immigrants from Japan were ineligible for citizenship, and in British Columbia, the ethnic Japanese were disfranchised regardless of their citizenship statuses.”

The Italian, as well as the Italian-Canadian and German-Canadian, populations were not a target of racial persecution or exclusion because they could naturalize if they chose to. Once they were naturalized, they had the same rights as any other American or Canadian citizens. The Italians and Germans who did not have American citizenship became enemy aliens when the war was declared against their countries. They became a target of some restrictions, such as a curfew order, but no military orders were issued to exclude them based on ethnic categories from the military defense areas.

The internment of Germans and Italians were based on the individual scrutiny concerning their loyalty or allegiance to their home countries that were adversarial to the United States or Canada. However, she adds, “in many cases, their internment seemed to have been unjustified, too.”

When watching the Karate Kid the other day, I was recently reminded that Japanese Americans were allowed to enlist in the army and engage in active combat (e.g. the “Go For Broke” 442nd battalion). However, there was resistance from the Canadian government to allow JCs to enlist until close to the end of WWII when, at the behest of the British, JCs were allowed to enlist as interpreters who worked in India. What difference did that make?

“The military valour of Japanese Americans undoubtedly helped the general acceptance of the ethnic Japanese in the United States after World War II. Military veterans, such as Daniel Inouye, became influential in the state politics of Hawaii and later in the US Congress; and his prominence, as well as that of other elected officials and Washington lobbyists (Mike Masaoka was also a veteran), advocated for the social and economic advancement of Japanese Americans in general.”

Izumi further explains why Japanese Canadians were not allowed to enlist in the military until close to the end of the war:

“Racism against Japanese Canadians was also questioned by the Canadian public after the war, especially when the Canadian government attempted to deport Japanese Canadians to Japan against their will in 1946 and 1947. The opposition was so strong that the government rescinded the forced deportation policy and only sent those who agreed to be ‘repatriated’ to Japan. But other than the opposition to the deportation of Canadian citizens of Japanese ancestry, Japanese Canadians did not have much support from the general public; they did not have the same prominence Japanese Americans had, because of their military service during World War II.

“Personally, though, I think it is sad that so many Japanese American young men with a bright future had to sacrifice their lives for their community to gain full citizenship rights which should have not been taken away from the beginning. From this point of view, I would be wary of emphasizing Japanese American Nisei’s military valour too much, because this generates the logic that one’s birthright citizenship is a reward for your sacrificial patriotism. I believe that one’s birthright citizenship is inalienable, and people have the right to follow their conscience even at the time of war. If your conscience is against the war, you should be able to serve your country in other ways than serving as military combatants. And as citizens, I think sometimes you have to oppose a war. I do not believe that you necessarily have to be willing to kill for your country in order to enjoy your citizenship.

“I also feel a little uncomfortable to see that so much emphasis is placed on the fact that Japanese Americans were loyal to the United States in order to say that their incarceration was unjustified. This logic can justify incarceration of other groups who are not necessarily rendered loyal to their nations. I wrote about this problem of discourses around Japanese American internment/incarceration in my book, The Rise and Fall of America’s Concentration Camp Law: Civil Liberties Debates from the Internment to McCarthyism and the Radical 1960s (Temple University Press, 2019).

“In Canada, Japanese Canadians were not allowed to return to the BC coast until 1949. In 1946 and 1947, about 4,000 people were deported to Japan. The Federal Government blamed Japanese Canadians for arousing racial antagonism against them, because they lived clustered in ethnic communities in British Columbia. The government blamed the victims of racism and punished them, instead of stopping racism. Some British Columbian politicians hated Japanese Canadians so much, that they made sure that all their properties were sold and Japanese Canadians had nothing to come back to. The combination of racism at the provincial level and the federal level created the policies of dispossession and deportation, and it delayed the ending of civil rights violation of Japanese Canadians. I agree that it was unbelievably cruel.

“But Canada was not the only country that deported citizens of Japanese descent. In the United States, over 4,000 Japanese American citizenship renunciants were sent to Japan from the Tule Lake Segregation Center.

“Over 2,000 Japanese Latin Americans were taken to the United States to be used for the hostage exchange between Japan and the United States. Over 700 of them were sent to Japan, and the rest became stateless people in the United States. This is also a very cruel policy, and it affected its victims’ lives even longer in the postwar period, as they were not only deprived of their livelihood but were stripped of their citizenship.

“Australia also implemented cruelty on the ethnic Japanese who resided in and around the country. There were about 1,000 Japanese living in Australia at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, and virtually all were interned soon after the war started. They were treated as prisoners of wars. In addition, Australia took Japanese civilians living in the surrounding countries, such as Dutch East Indies and New Caledonia, along with Japanese POWs in those regions, and incarcerated them in the POW camps in Australia. They were deported to Japan after the war was over.

“There were civilian Japanese men who were married to local women in Australia and the surrounding regions, who were forcefully separated from their families and incarcerated in Australia. These men were all sent to Japan, even though some requested to be reunited with their families when the war was over. Most of these families were never reunited after the war.”

© 2023 Norm Masaji Ibuki