Japanese people remaining in the Philippines file lawsuit

What is the definition of "Japanese-American"? According to the dictionary (Daijirin), it is "something that has Japanese descent or a person." Similarly, the definition of "Japanese-American" can be thought of as someone who has Japanese descent (bloodline, blood ties).

According to this, Japanese people would also be considered Nikkei-jin, but this is not generally the case. This is because they have no other bloodline. In general, when we say Nikkei-jin, we are referring to people who have bloodlines other than Japanese. However, second-generation Japanese born to Japanese couples who immigrated to South or North America, and third-generation Japanese born to two such second-generation Japanese, are also called Nikkei-jin, even if they have no other bloodline other than Japanese.

They are referred to as Japanese Americans or Japanese Brazilians, but in this case "American" and "Brazilian" seem to refer to nationality. Looking at it this way, we can see that even when the same "someone" is used, it can refer to bloodline or nationality.

The people of Japanese descent left in the Philippines, whom I mentioned at the end of my last column, could be considered to be of Japanese descent, but in terms of nationality they could also be considered Japanese. They were of Japanese descent born to Japanese fathers and Filipino women, and under the Japanese Nationality Act at the time, a child's nationality was determined by the father's nationality, so if the father was Japanese, then they should have become Japanese.

However, in the Philippines, one of the battlefields of the Asia-Pacific War, his relationship with his father was severed during the chaos of the war and after, and evidence of their relationship was also lost, making it impossible for him to prove that he was Japanese. In addition, he had to hide his Japanese ancestry due to the Filipinos' resentment and hatred towards the Japanese military, and for other reasons, he did not seek to become a Japanese.

Over time, anti-Japanese sentiment subsided, and more and more people began to feel a desire to clarify who they were and to confirm that they were Japanese. Even now, 78 years after the end of the war, there are people who wish to regain their Japanese nationality.

The Japanese government's slow response

Starting in the 1980s, journalists began to expose these Japanese people who remained in the Philippines, and efforts were made to identify them and help them regain Japanese citizenship, just as they had done for the Japanese orphans left behind in China. But the government's response was slow. This is made clear in the book Hapon: The Long Postwar Life of Philippine Nikkei (Daisan Shokan, 1990).

At the time, the author, Shun Ohno, interviewed the head of the Migration Division of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs' Consular and Migration Affairs Department and asked him how he perceived this issue. His response was hard to believe. Here is what he said:

"Even Japanese people have the freedom to choose their nationality. They can become naturalized or become permanent residents. After the war, if they wanted to return to Japan, they could. At the time, Japan was a burnt-out country, and there was no difference between it and the Philippines. After that, Japanese people worked hard and became an economic powerhouse, but the same could not be said for the Philippines. And now they are saying they want to return to Japan... They should take responsibility for their own decision to stay in the Philippines back then."

This section chief had no understanding at all of the circumstances in the postwar Philippines in which Japanese-Filipinos who had lost their fathers were not in a position to act of their own free will. It can be said that he had no imagination at all that this situation was the result of Japan's selfish military actions, which had made the Philippines a battlefield.

Furthermore, despite the fact that Japan used other countries as its battlefield, resulting in many civilian casualties, and destroying their land, which likely hindered their healthy development, his words, which seem to praise Japan for its remarkable post-war recovery, not only fail to convey an ounce of awareness of its war responsibility, but even come across as arrogant and condescending.

Furthermore, the section chief asked Ohno, "Why do you make such an issue of Japanese people in the Philippines?" He then cited the fact that the government provides both paid and unpaid aid to the Philippines, and explained that giving aid only to those with Japanese blood would draw criticism locally, a typical bureaucratic justification for not addressing the issue.

Philippine Japanese Legal Support Center

One cannot help but think that if the government had been more proactively involved from this point on, the problems of many people seeking confirmation of their Japanese identity could have been resolved, as private-sector-led efforts to help restore their nationality have been ongoing for many years and continue to this day.

The organization that is carrying out this support is the Philippine Nikkei Legal Support Center (PNLSC), a certified nonprofit organization that was established as a voluntary organization in 2003. One of its representative directors, lawyer Hiroyuki Kawai, is the author of books such as "Nuclear Power Lawsuits Will Change Society" (Shueisha Shinsho), and in recent years has also become known for his work on anti-nuclear lawsuits.

Kawai was born in Manchuria in 1944 and returned to Japan when he was one year old. During this time, he lost his younger brother. Based on his own experience, he has been working on humanitarian assistance activities to help Japanese orphans left behind in China acquire Japanese citizenship.

"It was the Japanese military that crushed the economically prosperous Japanese community in the Philippines, which lived in harmony with the local people, so I believe it is the responsibility of us Japanese to rebuild it. To do that, we must find the parents of as many of the second-generation Japanese who remained behind, confirm their nationality, establish their identity, and make it easier for third- and fourth-generation Japanese to obtain permanent residence visas" (PNLSC website), says Kawai.

The other representative director, Norihiro Inomata, was born in 1969. He studied sociology at the Asian Social Institute in Manila and was involved in digging wells in rural areas with local NGOs. He later worked for the NGO in the Philippines and Myanmar.

PNLSC works with the Philippine Japanese Association and other organizations to assist with nationality issues, identification searches, and meeting with relatives, and has also conducted on-site investigations. Many second-generation Japanese-Filipinos do not have a family register or do not know where their family register is located. For these people, there is a method known as "shusoku" (a process of registration), whereby a new permanent domicile is established and a family register is created with the permission of the family court. It is not easy to gain approval, but as a result of support, the Idebata sisters, second-generation Japanese-Filipinos, were the first to be granted permission to register in 2006. Support for registration continued after that, and as of November 2017, the number of people who have been granted permission to register reached 200.

He has also worked on politics, such as collecting signatures for a petition to the National Diet calling for the Japanese government to investigate and provide support to Japanese orphans left behind in China. In 2020, Kawai was involved in planning and producing the documentary film "Japanese Forgotten Things: Japanese Left Behind in China and the Philippines" (written and directed by Hiroyasu Ohara), which depicts Japanese left behind in the Philippines and Japanese orphans left behind in China, and spread awareness of the existence of Japanese left behind in the Philippines.

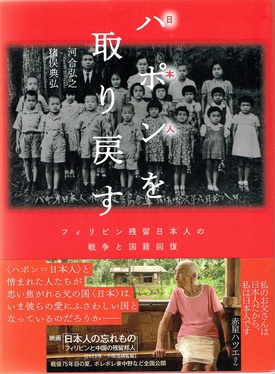

Reclaiming Japan

At the same time as this film, Kawai and Inomata co-authored a book on the activities of the PNLSC and the issue of Japanese people remaining in the Philippines, "Reclaiming Hapon: The War and the Restoration of Nationality for Japanese Left in the Philippines" (Korokara Co., Ltd.). It includes basic information on providing support, such as "the position of Japanese people left in the Philippines" and "what they want," as well as the voices of Japanese people left in the Philippines that were interviewed, and a historical look at the footsteps of Japanese people in the Philippines, divided into pre-war, wartime, and post-war periods. The book clearly outlines the historical background, the hardships suffered by second-generation Japanese people, and the need for support.

The war caused suffering for second-generation Japanese who were caught between the Philippines and Japan. One example given in the book is that Carlos Teraoka, the third son of a second-generation Japanese, had two older brothers, the eldest of whom was shot to death by the Japanese Military Police Headquarters on suspicion of spying simply for possessing American cigarettes. Meanwhile, the second son, who worked for a Japanese affiliate, was killed by Filipino guerrillas.

Inomata says his heart aches every time he walks around the Philippines researching Japanese left behind in Japan. Just knowing that he, a Japanese person, has come to see them makes them cry and talk about their Japanese roots, which they had previously kept quiet for fear of persecution. This is similar to what photographer Tsuneo Jiang, who interviewed Japanese orphans left behind in China, said about how they would ask for his business card when he met them. The Japanese orphans wanted some kind of connection to Japan.

Given historical reasons, Japanese people have an obligation to respond to the earnest desire of the remaining orphans and second-generation Japanese orphans to confirm that they are Japanese and who they are.

According to the PNLSC, there are still approximately 900 second-generation Japanese who remain in the Philippines whose identities are unknown, and an estimated 600 more who are effectively "stateless" because they do not have family registers.

As Kawai says, "We are on the brink of an irreversible era in which the problem itself will 'disappear' before it has even been 'solved.'" It is essential that legal procedures be carried out as quickly as possible, while at the same time the government make political decisions to resolve the problem.

© 2023 Ryusuke Kawai