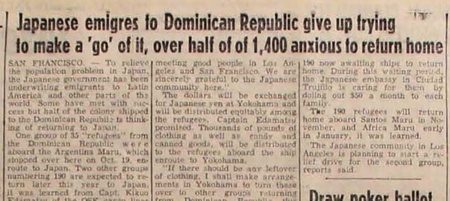

As mentioned, the Japanese government’s postwar project to resettle Japanese citizens in the Dominican Republic, which was troubled from the outset, collapsed in mid-1961 after the assassination of Dominican strongman Rafael Trujillo. Within a year, more than half the people involved returned to Japan, while the largest fraction of the others moved to Brazil or other countries. One of the few shining elements of the story is that of the impressive mobilization of the Japanese American community to assist the refugees.

In October 1961, as ships arrived in the Dominican Republic to repatriate Japanese, community representatives in the United States, learning of the plight of the refugees, rapidly organized the collection of money and clothing. The Shin Nichi Bei reported that the OSK cargo liner Argentine Maru, carrying the initial party of 20 adults and 14 chldren, was set to arrive in San Francisco, and several local community groups announced plans for a relief drive.

Within a week, according to Taiichi Kawase, local Nichi Bei Kai executive secretary, the local Japanese independent church made an initial donation of $42 while the Japanese Seventh Day church sent $180. Another $20 was received from the Wakayama group while $2 came from Mae K. Fujita of Berkeley. Bundles of clothing for the refugees were delivered to the YMCA building at 1830 Sutter and the Nichi Bei Kai office in the local JACL building at 1759 Sutter St. Community members also donated thousands of pounds of clothing as well as candy and canned goods for distribution to the refugees.

According to an article in the Pacific Citizen, by the time the Argentine Maru arrived, sympathetic people in the Bay area had raised a total of $1,683.25, which Kawase turned over to Captain Edamatsu after coming on board to meet with the refugees. The money included 200,000 yen in Japanese currency, as well as greenbacks, silver dollars, nickels, and even pennies.

The article reported that representatives of the refugees—Yoshizo Hagiwara, 34, from Kagoshima, and Shizuo Kawamura, 38, from Kochi prefecture—were visibly moved by the gift from the local community.

“We have suffered so much during our attempt to settle in a new land and we were kicked around so much by bureaucratic people in the past several months, before boarding this ship, [that] we have almost come to lose faith in human goodness,” one of the refugees explained. “But we have regained confidence in ourselves and recovered faith in God since our meeting good people in Los Angeles and San Francisco. We are sincerely grateful to the Japanese community here.”

Captain Kikuo Edamatsu announced that the dollars would be changed into Japanese yen at Yokohama and promised that they would be distributed equitably among the refugees. “If there should be any leftover of clothing, I shall make arrangements in Yokohama to turn these over to other groups returning from Dominican Republic this year.”

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles the board of the local Japanese Chamber of Commerce voted unanimously to provide financial assistance to the repatriates. Paul Takeda, manager of the Chamber, announced that monetary gifts and clothing would be accepted from volunteer donors at the Chamber office, and then delivered to the second and third contingents of refugees. Within a few days, the Chamber collected about $550 and four tons of clothes donated by Los Angeles area Japanese. When the Santos Maru, which was carrying the Dominican Japanese emigrants back to Japan, arrived in port in Los Angeles, Japanese Chamber of Commerce Eiji Tanabe, accompanied by Kakuo Tanaka and Ryohei Iwamoto, volunteered to make the presentation.

Saburo Kido, editor of Shin Nichi Bei, called on readers to donate their money, and especially their used winter clothing, so that the refugees from the tropics would have warm clothes to help them survive the winter in Japan. Even more, he said, their gifts would “serve as an encouragement to these disappointed and downhearted people that, there are people who are willing to extend a helping hand.” Interestingly, Kido claimed that Japanese Americans should be especially generous and sympathetic towards the refugees in view of their own family experience:

“Those of us who have heard about the experiences of our parents when they first came to this country could understand the hardships the Dominican refugees had to withstand. The Issei pioneers had to suffer and persevere while laying the foundation for us. The development of Imperial Valley, the Fresno area, the Yamato Colony in Livingston, Turlock, and Cortez are replete with stories of the sturdy pioneering spirit of the Issei who made their contributions towards the development of the West. What is being asked of us is not too great a sacrifice.”

The needs of the Japanese refugees from the Dominican Republic catalyzed a friendly rivalry between Northern and Central California Japanese communities and those from the South. After giving crucial assstance to passangers on the Argentine Maru, Northern community leaders, most of them Issei, organized a relief committee in support of those on the next boats. A total of $8,024.20 was received in the course of a second relief drive. About $600 was turned over to the refugee group aboard the Santos Maru in addition to that already raised by Southern California Japanese communities.

Most of the money was reserved for a third group of refugees who were set to arrive on the OSK’s Africa Maru. In the end, the 149 refugees aboard the Africa Maru were given $10 each, $500 from Southern California donors and the rest from the proceeds of the Northern California committee drive. Some six tons of clothing donated by Northern California Issei and Nisei was loaded aboard the Africa Maru during its local stopover, half to be immediately distributed to the refugees during the transpacific voyage and the remainder to be kept in an Osaka warehouse for use by future refugees.

By March 1962, four months later, the Southern California Japanese Chamber of Commerce announced that a total of about $950 cash and 12 tons of used clothing had been collected for the Dominican refugees, and that a total of 350 people had been aided. Asserting that only one ton of old clothes and $187 in cash remained to be distributed, the Chamber sent out further appeals for locals to donate clothing and money.

In April 1992, the OSK liner America Maru stopped in San Francisco. It carried 207 returnees (49 families) from the Dominican Republic. By the time of its departure some days afterwards, the 207 returnees abroad had received a total of $2,070 in cash, $1,535 from the local relief committee, and a further $535 from the Los Angeles Japanese community relief fund. They also received about 2 tons of used clothing from the local relief committee, and three further tons in Los Angeles. Among the group were 150 children. They received about $20 worth of candy from representatives of the Pine Methodist Church and nine cans of candy (worth $80) from Seiji Nakata, a local candy store owner. A. Fujita, a representative of the returnees aboard, expressed appreciation to the Japanese communities in California, stating "We are sincerely grateful for your kindness.”

In one sense, the humanitarian campaign organized by West Coast Nikkei communities in 1961-1962 was a postscript to the massive aid operation they had put into place a decade or so earlier, for relief efforts in Japan during the postwar occupation period. At that time, the Japanese people faced widespread devastation, and for so many, the support that they received from Nikkei communities saved them from starvation. Nevertheless, there was an important distinction. The Issei and Nisei who offered assistance to Japan during the occupation period were frequently supporting members of their own extended families, or at least aiding people from a native or ancestral country with which they were familiar and with which they retained ties.

Conversely, few if any Japanese Americans had met any of the refugees from the Dominican Republic at the time they arrived in California ports, or even were acquainted with any of those who had resettled. Their support and sympathy were unselfish, a product of benevolence. They were thus presumably all the more touching and welcome to those who had lost everything and were trying what they could to put their lives back together.

© 2023 Greg Robinson