Many Nisei were born as a result of picture marriages, which I wrote about in the last chapter of this series. Providing Japanese education for America-born children thus became an important mission of the Japanese community in Seattle. In this chapter, I will write about the Seattle Japanese School that was founded for the Japanese language education of the Nisei.

ESTABLISHMENT OF SEATTLE JAPANESE SCHOOL

In 1902, the Seattle Nihonjin-kai (Japanese Association) established the Seattle Nihonjin-kai Affiliated Elementary School as the first Japanese school in North America. In the beginning, there were four students and one teacher. The school changed its name to Seattle Japanese Language School in 1908.

The school was first run in the Nihonjin-kai’s building, possibly the one on Maynard Avenue above, and later moved to the basement of Seattle Buddhist Church. As the number of students increased, a new schoolhouse was built on Weller Street in 1912. The new building commanded a magnificent view of Mount Rainier from its second-floor window. This schoolhouse exists to this day as the main building of the Japanese Cultural & Community Center of Washington.

CONSTRUCTION OF BUILDING EXTENSION AND OPENING CEREMONY

At the end of 1917, a building extension involving the addition of four more classrooms on the east side of the first building was mapped out. The following is an article on this construction.

“Building Extension Committee” (Jan. 8, 1918 issue of The North American Times1)

The plans for the construction of the Japanese School extension are to be completed in the next 10 days or so. As chairperson Heiji Okuda and committee member Manpei Miyagawa will be returning home soon, the committee held various discussions yesterday at the Jitsugyo Club (business club). The donations so far have reached $6,789.10 and additional donations of $1,300 to $1,400 will be enough to get the project done.

It was decided that once those two members return, the contract for the new building should be finalized by vice president Chuzaburo Ito and other current members without the need for additional members. Afterwards, the accounting report needs to be submitted.

In the end, the meeting was dismissed with the decision that both collection-chief Jiro Iwamura and his assistant will finish up the remaining tasks after January without pay.

As we can see, the expansion of the Japanese School was made possible by donations from the Seattle Japanese community. The total donations were about $8,100, valued at about 16 million yen today ($123,184). The accounting tasks were handled by volunteers as well, showing how much dedication the Issei had for the education of their America-born children.

In May 1918, the Japanese School held the opening ceremony for the building extension, along with an student artwork exhibition.

“Arts Festival at Japanese School, Opening Ceremony After Building Extension” (May 11, 1918 issue)

An exhibition of student artwork and the opening ceremony for the building extension will be held at the Japanese School tomorrow, Sunday, from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. The ceremony will start at 3 p.m. in the schoolyard, led by master of ceremony and principal Kotaro Takabatake.

The ceremony will consist of the following: Greetings by MC. Singing of “Kimigayo” (national anthem of Japan) by all students. Report of academic affairs by the principal. Accounting report on building extension by building extension committee member Iwamura. Congratulatory speech by Director of Educational Affairs Department Akiyoshi, followed by Consul Matsunaga. Acknowledgments by chairperson Ito. Singing of the US national anthem by all students.

What is surprising about this program is that the students sang the Japanese national anthem, “Kimigayo,” first and America’s national anthem at the end. Most attended public schools on weekdays, like most other Americans, and studied at the Japanese School after that. Nisei children were thus placed in a hectic environment where they received both American and Japanese educations at the same time.

In those days, the Nikkei community was leaning more toward “Americanizing” themselves and were trying to raise their Nisei children in a way that would meet the expectations and goals of both countries.

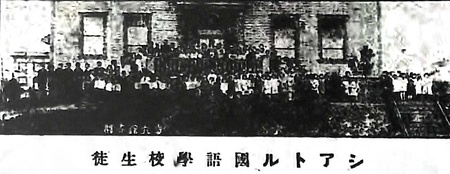

The January 1, 1920 issue has a group photo (below) of the students in front of the school building.

COMMITTEE FOR MAINTAINING JAPANESE SCHOOL

As the Japanese school became independent from the Nihonjin-kai, it was maintained and administered by the Committee for Maintaining the Japanese School. The school was operated by membership fees and donations. Here is an article on a general meeting of this group.

“General Meeting of the Committee” (Feb. 26, 1920 issue)

A brief meeting of the Committee for Maintaining the Japanese School was held last night at the Jitsugyo Club. A number of topics were discussed and voted on, such as the printing of graduation certificates, keeping the staff for cleaning classrooms, plans to hold a general meeting on March 4 to decide on increasing the membership fees of parents, as well as renaming the after-school session as the higher department. For reference, the average spending on one student at the school last year was $2.30 a month.

The monthly educational expense of $2.30 would be equivalent to about 5,000 yen ($38) today. According to some sources, the school had 187 students in 1919, and the total expenses of the school were $5,161 a year. This is worth about 10 million yen today ($674,000).

THE JAPANESE SCHOOL GRADUATION CEREMONY

The North American Times also published an article on the Japanese School graduation ceremony in the issue of March 25, 1918.

The 10th graduation ceremony of the Japanese School was held yesterday at 1 p.m. in the Nippon-kan (a Japanese theater on Main Street), with eight boys and six girls graduating. The ceremony began with principal Takabatake’s greeting speech and carried out solemnly. The gifts distributed to each student in attendance were donated by Furuya-shoten (the Furuya Store), Toyo Boueki (trading), Seattle Shokin Bank, Nichibei-nakagai, and Hiraide-shoten. The names of current students from grades 1 to 8 who won first prize (four students), second prize (15 students), and special prizes (30 students) were posted. At 12:30 p.m., a commemorative photo was taken at the school and Mrs. Furuya handed congratulatory gifts to all graduates.

BELLEVUE JAPANESE SCHOOL

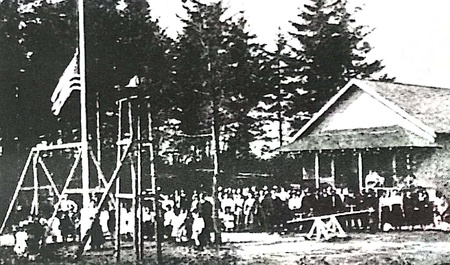

The North American Times (April 8, 1918 issue) published an article on the opening ceremony of the newly built Bellevue Japanese School.

With over 20 school-age children, the decision was made to open a Japanese school in Bellevue Village. Appointing Mrs. Okamura as a teacher, the opening ceremony of the school was held yesterday. Among the guests were Nihonjin-kai secretary Nakajima, Nakamura, Toshikichi Kanbe from Taihoku Nippo, as well as Arima and some others from the (NAT) headquarters of the North American Times.

Director Matsuzawa led the ceremony as MC, Keikichi Yamagiwa read the Imperial rescript with solemnity, and Arima, Nakamura, Nakajima, and Ryuzaki gave congratulatory messages and speeches.

The ceremony was followed by a reception with some treats and tea, where people enjoyed themselves very much. Suda from Bellevue invited some guests from Seattle to his house and welcomed them warmly with lunch. By the way, Mrs. Okamura is from Osumi, Kagoshima and was engaged in elementary education for a long time in her hometown.

OPINIONS OF JAPANESE SCHOOLS

The North American Times president Sumikiyo Arima, who gave a speech at the opening ceremony of the Bellevue Japanese School, discussed it in ths column, “Some Things I Have in Mind” (Apr. 8, 1918 issue).

Though we are 100% Japanese, our descendants are American citizens. Because they are citizens, their education should primarily be based on the American one and their Japanese education should be limited to instruction in the Japanese language. For children born in the United States with US citizenship and receiving US educations, we should not immerse them in the nationalism of Japan or in Japanese education. Once other Americans find out about it, they will object to Japanese schools for certain and further try to ostracize the Japanese as a race which is absolutely incapable of assimilating.

With that said, Japanese schools should be aimed at fostering good-natured people, and teaching just the language at the same time would be enough to fulfill its purpose. In other words, they only need to teach children that they should follow ethics, love others, respect justice and contribute to society. That way, those young kids will become kind-hearted US citizens, if they grow up in America, and be loyal Japanese citizens, if they return to Japan and live their lives there.

During World War I, when this article was written, America as a society was at its peak in pushing for the Americanization of all foreigners in the country. Arima is emphasizing the importance of operating Japanese schools in a way that would help the Nisei adapt to American society.

The below article was written at the request of Sumiyoshi Arima, chief of the Portland branch of The North American Times, quoting Principal Manro Senoo’s opinion on Japanese schools.

“Taking the Job at Portland Japanese School” (Jan. 1, 1919 issue)

“Japanese schools are designed and planned in each region. Abiding by conventions and seeking to meet the expectations of the times, the plan is for the betterment of the future, as they balance out the requests of parents or those of experts. Accordingly, the “US-dominant, Japan-subdominant” principle is the fundamental principle of our Japanese school. As this is the core philosophy, the purpose of Japanese schools is to teach ‘the language of Japan’ and nothing more.”

Note:

1. All article excerpts are from The North American Times unless noted otherwise.

*The English version of this series is a collaboration between Discover Nikkei and The North American Post, Seattle’s bilingual community newspaper. This article was originally publishd on February 14 and March 14, 2023 in The North American Post and is modified for Discover Nikkei.

© 2022 Ikuo Shinmasu