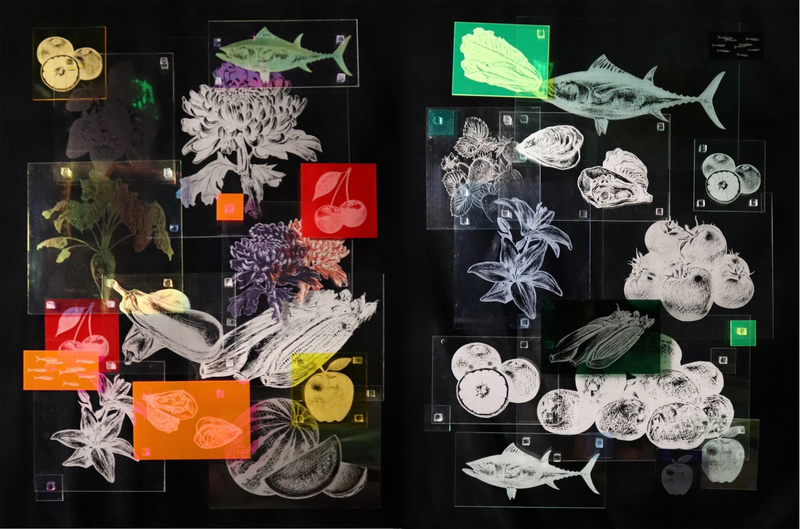

Artist-in-residence Kanon Shambora used her time at Densho to explore the roots of Japanese American identity. Their culminating Print Garden pays homage to early Issei and Nisei, as well as to the crops and species that they cultivated and caught. Shambora laser cut and printed her drawings onto acrylic plates, then welded them together in two panels that now hang in the Densho Community Room. In this artist statement, Shambora shares what they learned of the history and how it inspired their work.

* * * * *

The United States of America is often regarded both home and abroad as the land of opportunity. Due to its reputation, people from all over the world make their way here, giving us the highest immigrant population out of any country.

In the mid-19th century, the first influx of Asian immigrants arrived. The Issei (first generation Japanese immigrants; 一世), like many other Asian immigrants at the time, were contracted to work on plantations in what was then the Kingdom of Hawai`i and on farms, lumber mills, railroads, and canneries of the West Coast. Trying to escape economic hardships in their home countries, they hoped to prosper in a new land.

While some did find success, many others found adversity. Alien land laws, housing discrimination, and nationality-based pay discrepancies situated Issei on the lower end of the socio-economic ladder.

Despite being poorly compensated, their work was essential. Issei and Nisei (second generation) turned to farming, fishing, and small businesses, soon establishing themselves as a vital part of the US economy. In the early half of the 20th century, Japanese American families alone cultivated 35% of the produce grown in California and supplied around 75% of the produce in Washington State’s Puget Sound region.

On December 7th, 1941, Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. A couple months following the strike, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order authorized the “exclusion” of anyone deemed a threat to national security from designated military areas. While its language does not specify any one ethnic group, a disproportionate number (over 120,000) persons of Japanese descent were held in incarceration sites across the US. Two federal agencies — the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) and the War Relocation Authority (WRA) — were formed to carry out and maintain Japanese American removal and subsequent incarceration.

No US-based Japanese Americans were ever found guilty of espionage or sabotage, and little evidence suggested that they would be. In reality, xenophobia, racism, and economic interests that had been in play for decades motivated the incarceration of civilians and resident immigrants. Lobbyists representing competing commercial entities and nativist groups fought hard for the passage of EO 9066.

Members of the Department of Agriculture and the Office of Indian Affairs also conveniently became WRA administrators, and they were strategic in deciding where to place incarceration sites. Several of these “camps” were built on Indigenous land that had agricultural and industrial potential for settlers (irrigation ditches, railroads, etc.).

The US government, under the guise of national security concerns, redistributed a massive labor source to these areas. EO 9066 became a tool to justify and necessitate an ongoing effort to push Indigenous people out of their own territories and ready them through the labor of Japanese prisoners for settler development and profit. After the war, land on camps such as Heart Mountain, Minidoka and Tule Lake were given away in homestead lotteries to US citizens as private property. In this way, Japanese American incarceration helped advance settler colonial initiatives.

Not only was this devastating for both Japanese American and Indigenous communities, but this relocation effort took a considerable toll on the West Coast’s economy. Farms, markets, and co-ops built over the course of a few decades were all forcibly abandoned within the span of a few days. To address this labor shortage, the US enacted the Bracero Program a few months later. Japanese labor was eventually replaced by Mexican workers brought to the US through short-term contracts.

* * * * *

For the past year, I was given an opportunity to create a body of work responding to Densho’s archives. Densho is an organization dedicated to preserving the history of Japanese American incarceration. They have a vast collection of stories, interviews, newspaper clippings, photos, etc. of all things related to Japanese American history.

The agricultural industry was a fundamental means of survival for Japanese Americans. In response to this element, I proposed the idea of a Print Garden. I wanted to quantify the achievements of Issei and Nisei by displaying the crops that they had produced.

What followed was a year of drawing fruits, vegetables, flowers, and fish that were representative of the crops and species Japanese Americans cultivated and caught. Using a laser cutter, I printed these drawings onto translucent, acrylic plates and welded them together to create two large panels of crop prints.

My hope is that upon viewing these works, people are reminded of the losses brought on by EO 9066. Japanese workers were no longer around to do the farming/selling, and most of their communities (called Nihonmachi or Japantowns) permanently shut down. On top of material losses, their abrupt removal and indefinite incarceration left its mark on survivors and subsequent generations of Japanese Americans. As a means of survival, incarcerees pushed their children to work within a broken system, to strive to be 200% American, and to neglect aspects of their own culture.

Despite the cruelty of it all, I wanted to make something that is also vibrant. The acrylic plates are best viewed with reflected light, and they are structured to be suspended. This medium felt like an appropriate way to capture the spirit of pre-war Japanese American communities. These plates are a celebration of their work and the tight-knit networks they had spent so many years fostering.

* * * * *

In the US, we aren’t very conscious of the origins of our resources (especially when it comes to food). The hard work that goes into the production and delivery of these resources falls on a largely immigrant class, and when we interfere with these labor forces, the repercussions can be calamitous. Japanese American incarceration illustrated this loss very clearly.

Today, immigrant farm workers in the US constitute roughly 73% of this industry’s labor force. While my work speaks specifically to Japanese American agriculture, immigrants today are subjected to the same xenophobic and racist power structures that operated back then.

Just this past year we observed a similar phenomena with Florida’s passage of Senate Bill 1718. This bill made it illegal to “knowingly employ, hire, or recruit” undocumented persons, yet an estimated 10% of the people working in Florida at that time fell under this category. The result was a mass exodus of workers trying to escape the implications of this new law. People who had already built a life here were forced to leave behind their belongings, their families, and their jobs.

Aside from the mental and physical distress provoked by this bill, legislators failed to consider the value of these workers’ labor. I can quantify it for you: an estimated $12.6 billion loss over the course of one year, according to the Florida Policy Institute. But that’s not even the point. Who grows, harvests, processes, cooks, packages, and transports our food? And where would we be without them? Where would any American industry be without immigrants?

I want this installation to honor the contributions of Nikkei immigrants of the past, and to prompt us all to foster appreciation — and accordant respect and rights — for immigrants today.

* Learn more about Densho’s Artist-in-Residence program here.

Further Reading

“Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration (1942).” National Archives, January 24, 2022.

Stephanie Dawn Hinnershitz. “Lessons From the Incarceration and Forced Labor of Japanese Americans During World War II.” Scholars Strategy Network, May 30, 2018.

Hana Maruyama. “How Japanese American Incarceration Was Entangled With Indigenous Dispossession.” KCET, August 18, 2022.

Lisa Morehouse. “Farming Behind Barbed Wire: Japanese-Americans Remember WWII Incarceration.” NPR, February 19, 2017.

Andrew Moriarty, ed. “Immigrant Farmworkers and America’s Food Production – 5 Things to Know.” FWD.us, September 14, 2022.

“Prisoners at Home: Everyday Life in Japanese Internment Camps.” DPLA.

Resistors: Legacy of Movement from the Japanese American Incarceration, Wing Luke Museum, Special Exhibitions Gallery, on view October 14, 2022 through September 18, 2023.

Statista Research Department. “Countries with Highest Migrant Populations Worldwide.” Statista, June 16, 2023.

Natasha Varner. “How Japanese and Mexican American Farm Workers Formed An Alliance That Made History.” The World, August 15, 2016.

Anagilmara Vilchez and Noticias Telemundo. “Florida Immigrants Detail Their Exit Following DeSantis Immigration Law: ‘I Had to Leave.’” NBC News, June 25, 2023.

*This article was originally published in the Densho’s Catalyst on December 23, 2023.

© 2023 Kanon Shambora