The next task on Elliott’s political agenda was to extend the border of the exclusion zone to all eastern portions of Tulare and Kern County. Initially, the Western Defense Command announced on March 2, 1942 that all Japanese Americans living west of Highway 99 in Exclusion Zone 1 were to report for incarceration. This, and the Army’s decision to allow for voluntary migration in March 1942, led to thousands of Japanese Americans to move to the eastern parts of Tulare and Kern counties which were part of Exclusion Zone 2.

The new migrants soon became a political target of Elliott, who swore to remove all Japanese Americans in his district. On April 16, 1942, the Tulare County Farm Bureau directed a statement at the Army and Elliott that they would “disfavor on any effort to make Tulare County the dumping ground for Japanese that are considered undesirable in other areas of California.” Director of the Lindsay-Strathmore Irrigation District and Sunkist representative Richard Richard Stark also wrote to Bendetsen arguing that Japanese Americans in all of Tulare County needed to be expelled to protect the water sources of the region.

In response, Bendtesen told Stark on April 24th that it is unlikely that Japanese Americans would be removed from Zone 2 and the irrigation district was a low priority:

“The responsibility for the protection of the facilities of the District rests fundamentally and inherently with the District itself and with local enforcement authorities. Even in the event the requested extension was granted, and as a result thereof all Japanese were excluded from the District, this in itself would be no guarantee as to the security of the works if left unprotected and unguarded. They would still be vulnerable to a planned and organized sabotage attack.”

Despite Bendetsen’s reply, Elliott and the Tulare groups continued to push for extension of the exclusion orders to Zone 2. A few days later, on April 27, Elliott wired Bendetsen another message stating he needed to remove Japanese Americans coming into eastern Tulare County:

“Has a decision for their removal been reached? Advise me by wire. My people becoming very much alarmed. When can we expect Japanese removed from Eastern and Northern Tulare County? You saw the danger.”

On May 4, the Western Defense Command announced that all Japanese American families in Tulare County residing west of Highway 99 would be required to report to assembly centers in the following days.

Elliott continued to push Bendetsen and Dewitt to modify their exclusion orders to include the entirety of Tulare and Kern counties. In a letter to Stark from May 9, 1942, Elliott confidentially instructed Stark to use the local civic organizations in Tulare to pressure the Army to remove all Japanese Americans from the county:

“After talking with officials higher than the General, I am confident that things will be beginning to shape around where consideration will be given our side of the picture, and I do not believe I am wrong in advising you that by the end of this month, or sooner, there will be a change in the boundary line in Tulare County, and it is likely that all Japanese will be moved from the State of California.

You realize, Dick, that no publicity can be given this suggestion, but I would suggest that civic organizations continue to urge him to remove all Japanese. I cannot help but believe that the course I have taken here was responsible for the visit of Col. Bendetson and Mr. Eisenhower, and I assure you that I will continue my operations for the eventual removal of all Japanese.”

Stark followed through on Elliott’s suggestion and began rallying various groups to push for the removal of Japanese Americans from the area. On May 14, Stark reported to Elliott stating that he would organize a meeting between the American Legion, the Farm Bureau, and agricultural organizations to strategize lobbying for the removal of Japanese Americans from Tulare. The same day, Stark wrote a letter to Bendetsen pushing him to extend the exclusion zone further east, stating that “we in the area are left exposed to danger in order to simplify the job of the surveyor.”

The ploy worked; on May 18, Tulare County Sheriff John Loustalot reported that the Western Defense Command had extended their orders to require all Japanese Americans living in Tulare and Kern County. On June 6, 1942, the Western Defense Command announced in Public Proclamation No. 6 that all Japanese Americans would be removed from Zone 2.

The order was not enforced for a month; on June 16, 1942, Elliott wrote back to Stark reporting that the Army would move all Japanese Americans from Zone 2, including those in Eastern Tulare County, into assembly centers when room was available. Elliott finished his response with a promise to “continue to keep after this problem until we are rid of them.”

Bendetsen kept Elliott apprised of the situation; on June 24, when Elliott telephoned Bendetsen about the status of Japanese Americans in eastern Tulare, Bendetsen informed him that the Army had issued orders restricting Japanese American movement and planned to send them to assembly centers when possible. Satisfied, Elliott stated that he would try to pacify the anti-Japanese population of Tulare.

While it is difficult to say that Elliott was the sole reason behind the Army’s decision to extend the evacuation orders to Zone 2, I would argue that he played a central role in convincing the Army to modify its policy by working together with local interest groups. In their deceitful final report, the Western Defense Command stated that their reasons for extending the exclusion zone were “to alleviate tension and prevent incidents involving violence between Japanese migrants and others.” The decision caused additional undue suffering to approximately three thousand Japanese Americans who settled east of the first exclusion zone line to avoid incarceration (a total of five thousand, including those from Fresno County, were sent from Zone 2 to camp). While several groups in Tulare did threaten violence against Japanese Americans, the Western Defense Command’s decision was based on the unjustifiable logic of forcing Japanese Americans into camp for their purported “safety” rather than protecting their constitutional rights at home.

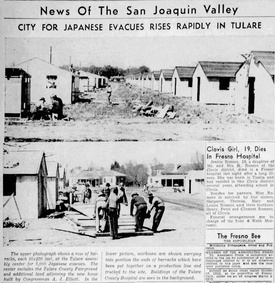

Between April 20 and September 4, 1942, the Tulare Assembly Center held a maximum population of 4978 prisoners. Japanese Americans from the Central Coast Counties (San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, and Ventura Counties), Los Angeles, and Sacramento Counties were sent to Tulare before being sent to Gila River Concentration Camp in Arizona. Coincidentally, those Japanese Americans from San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara County were from Elliott’s congressional district.

The Army recorded five deaths and eighteen births during the course of the Tulare Assembly Center’s operation. The cost of building the assembly center amounted to $300,000 ($5,744458 in current currency). Elliott received $1000 in compensation for the loss of his hay crop near the fairgrounds ($18,456 in current currency).

Even after the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, Elliott consistently spewed anti-Japanese hatred throughout the war and pushed for the permanent exclusion of Japanese Americans from California. On October 13, 1943, Elliott gave a speech on the floor of the House in opposition to allowing Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast. Elliott wasted no time in showing his racism; he told the House that “the only good Jap is a dead Jap and that is exactly what is going to happen” if they return.

The blatant bigotry of Elliott’s words spurred Representative Herman Eberharter to denounce Elliott’s remarks and highlight the sterling record of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the contributions made by resettlers to the war effort. Elliott’s words reached Japanese Americans as well; on October 30, 1943, the Manzanar Free Press reported on Representative Elliott’s speech on asserting that Japanese Americans had resettled back on the West Coast, and that, if not stopped, “violence and bloodshed would follow.”

On January 28, 1944, Elliott joined a group of representatives in signing a resolution that called for WRA Director Dillon S. Myer’s resignation for his “mishandling” of the Tule Lake uprising. It also called for legislation that would automatically denaturalize any U.S. citizens who expressed loyalty to a foreign state.

Elliott soon began his own crusade against Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes for a rumored proposal to have Japanese American farmers return to the San Joaquin Delta. The rumor surfaced during in the context of Elliott’s effort to counter a new bill proposed by Ickes that would offer parcels of land to returning soldiers. As a part of the bill, landowners in the Central Valley Project would only receive water access for properties between 10 and 160 acres.

Elliott slammed the proposal as “socialistic” and accused Ickes of wanting to bring in Japanese Americans to replace rebellious farmers. On May 15, 1944, the Tulare Advance-Register published a full-page editorial in support of Elliott’s renomination. The editorial also proposed the wild rumor that Japanese Americans in the camps were in cahoots with Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, and that Ickes was raising funds to have “loyal American congressmen” like Elliott defeated in their elections.

Ickes’s bill passed, and for the duration of 1944, Elliott devoted his attention towards passing legislation to exempt the Central Valley Project from water restrictions. On October 11, 1944, the San Francisco Examiner announced that Elliott’s bill died on the House floor.

For the duration of the war, Elliott was silent on the return of Japanese Americans. Elliott had no problems of approving a plan to use 3900 Japanese prisoners-of-war as farm laborers in the Central Valley – under the assumption that the prisoners would be returned to Japan. On September 27 1945, the Merced Sun-Star noted that Elliott consulted with the farm leaders of Tulare and Kern County before approving the plan. Elliott remained the representative of California’s 10th Congressional District until his retirement in 1949.

The story of Alfred J. Elliott and the Tulare Assembly Center demonstrated the integral role that Congress played in instigating, enforcing, and controlling the forced removal of Japanese Americans during World War II. Elliott’s creation of a political circus during the construction of the assembly center, along with his campaign to modify the exclusion orders, showed how some members of Congress increased the suffering of Japanese Americans by stirring their political base to garner support. Likewise, Elliott continued to politicize the return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast during the war as part of his work in Congress until the Supreme Court finally ruled in Ex Parte Endo on December 18, 1944, that Japanese Americans could return to the West Coast.

© 2024 Jonathan van Harmelen