A typical night at Grant “Masanduu” Sadami Murata’s house consists of a group of his uta-sanshin students gathered on his covered lanai for their weekly practice. Uta-sanshin, the art of singing while playing the Okinawan three-stringed lute, is practiced four days a week, each night with a different group of students. They sit on folding chairs and line up on one side of a couple of low folding tables – so the students can see the right and left hands of their sensei – where students place their binders filled with lyrics to songs they are working on.

Grant and his wife, Chikako, sit across from their students. Face-to-face instruction with no musical notes has been the foundation of the teaching style of Afuso-Ryu classical Okinawan music for more than 400 years.

From 6 o’clock p.h. (pau hana time after work) until about 8 or 8:30 in the evening, you can hear Okinawan classical or minyo music from Grant’s corner house in Aina Koa, Honolulu. It’s not unusual for a neighbor to stop and listen or just wave a hello to the sensei and his group.

At the end of practice, the master known as Masanduu Sensei will announce, “Otsukare sama deshita,” to which the students will reply, “Arigatou gozimasu” or “Ippei nifwe deebiru” (“thank you” in Japanese or Okinawan). And the students put their sanshin into their cases with latches closing with a clack-clack-clack, place them in their cars and come back to Sensei’s lanai to potluck.

Out come noodles, onigiri, chicken wings, poke and more. Small coolers filled with beer and hard seltzers. Some libations – Okinawan distilled alcoholic drink known as awamori, whiskey, shochu — contributed by students come out from Grant’s makeshift bar. It’s time to relax and talk story. If Tom Yamamoto, a student and teacher, brings his ukulele, there’s also a little casual music jam known in Hawaiian as kani kapila.

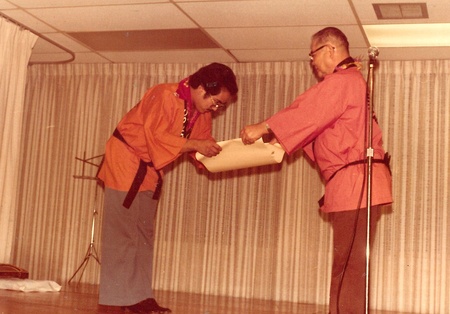

Grant is happy to have all the credentials of being a certified master of uta-sanshin, among Hawaii’s most respected in the Japanese and Okinawan performing arts community, and the only foreign-born judge of certification exams in Okinawa for the Afuso style of classical Okinawan music. Under his leadership, the school has spread to other Hawaiian islands such as Maui and Kauai, as well as Los Angeles. Many of these students have performed at Carnegie Hall in New York City, a milestone for Afuso Ryu and Okinawan performing arts reached in 2019.

But nothing can beat the twinkle in Grant’s eyes when he is connecting with people through music, stories and food — whether it’s on the lanai of his corner house in Aina Koa, Honolulu, on the grand stages of the Tokyo Imperial Theatre or at Carnegie Hall, performing alongside his mentor the late Grandmaster Choichi Terukina (1932-2022) – a National Living Treasure of Japan.

How did he get here? Grant spent nearly 40 years living up to the words of his sensei. It was under Choichi’s mentorship that Grant became a master of uta-sanshin and founder of Afuso Ryu Choichi Kai USA in Hawaii and Los Angeles.

Choichi Sensei always impressed upon his students that as performing artists, they should not just be hanabi (fireworks). Showing your talent might be spectacular for a while, but eventually, it will fizzle out and die.

“Instead, be a tree,” he stressed. To learn and pass the invaluable philosophy, wisdom and knowledge of Seigen Afuso (1785-1865), founder of Afuso-Ryu, is to continue a legacy indefinitely like a tree growing and flourishing with many branches and leaves until there are new seeds to be planted.

Students of Choichi apply this philosophy of community to life outside of the dojo, cultivate their inherent beauty to make the world a better place and spread the musical tradition. Grant has continued to plant trees of his own with Afuso-Ryu Choichi Kai USA. It is the largest Afuso-ryu organization outside of Japan.

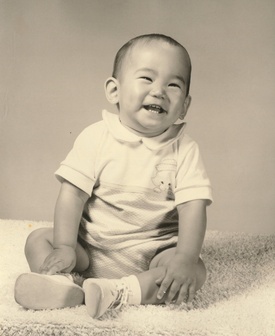

His story begins with his adoption at birth.

A CHOSEN SON

When Clarence and Judith Murata adopted their infant son in 1962, they never imagined he would become one of Hawaii's most respected leaders in the local performing arts community. As a young child, Grant's paternal grandmother, Margaret Hanayo Murata, encouraged Grant's desire to explore Japanese, and soon after, Okinawan cultural arts.

According to Grant, his Japanese American adoptive parents showered him with much love and affection. Worried his son might one day get teased for being adopted, Clarence Murata said to him, “Other parents, when they have babies, they gotta take home what they get. But we chose you to be our son.”

Sure enough, in elementary school, when a girl pointed out to Grant that he was adopted. He told her, “Yeah, your parents had to take you home. But mine chose me!” After getting called into the principal’s office, Grant's father went in to defend his son saying that he wanted to make sure his son knew that being adopted was as special and wonderful as he was.

Grant’s love for cooking was also fostered from a young age. “Every Friday, I would have to catch the bus home and I would help my grandma cook. I remember her steak and lemon meringue pies. And since it only took one Meyer lemon to make a pie, my dad used to point to the lemon tree and say, ‘Look, on da tree get five pies!’” Grant said, laughing.

Clarence was kept busy shuttling young Grant to numerous lessons: Japanese and Okinawan dance, koto and sanshin. From age 12, Grant tagged along with Hawaii’s Issei and Kibei-Nisei musicians. This Hawaii-born Yonsei was so fascinated by the Japanese and Okinawan culture, he listened and watched the elders, soaking up their stories, dialect, and mannerisms like a sponge.

His love for bon dance led him to Henry Masatada Higa, one of many sensei who would support Grant who was so eager to learn anything and everything from his elders. At age 19, Grant began teaching sanshin and also started a group called Sansei Minyo Kenkyuu Kai. A few years later, on a trip to Hawaii from Okinawan, Choichi Terukina made an effort to meet Grant. He had heard of Grant's reputation as a sanshin musician and wanted to meet him. In 1983, Grant became the grandmaster’s student.

STARTING AFUSO RYU CHOICHI KAI

Grant’s choice to pursue the art of uta-sanshin came with some challenges. Kenton Odo, one of Grant’s first students, said his sensei did not know he was Okinawan at the time and took “flack” for not having that heritage.

“Yet he still wanted to play the music in the worst way,” Kenton said. He added that he was inspired that his teacher grew up speaking English at home, but learned to read and write Japanese and speak Uchinaaguchi, the Okinawan language, without any formal lessons.

When Grant became Choichi Terukina’s student in 1983, he also committed himself to catalyzing the Afuso Ryu uta-sanshin movement in Hawaii. Today, the Afuso Ryu “family” includes more than 200 former and current students, three shihan (master instructors) and more than 100 mago-deshi (descendant students) – all hold hard earned certifications from the main Afuso Ryu organization in Okinawa.

In November 2018, Grant held the first-in-Hawaii solo performance by a master uta-sanshin performing artist as a rite of passage directed by the grandmaster. He was encouraged by a former consul general of Japan to hold his performance that year to align with the 150th anniversary of the Gannenmono, or “first year people” — pioneers who traveled to Hawaii in the first year of the Meiji era in 1868 and became Hawaii’s first Japanese immigrants.

Hundreds came to celebrate Grant’s milestone performance that included classical and folk style uta-sanshin with dance and storytelling – marking another step in the rise of the Afuso tradition in Hawaii.

A personal turning point was triggered in 2011, when Grant’s seven-year-old son was diagnosed with severe encephalitis. Due to the severity of the condition, the medical team’s prognosis was that he would make only a partial recovery and experience limited independence after rehabilitation. It was likely that he would be a highly dependent invalid, unable to walk or to talk and require a special wheelchair and bed.

Grant shared the bad news with his teacher over the phone. In a story published on the Asia-Pacific Journal website, the conversation went like this:

“The doctor gave us a really down to earth analysis of this boy,” Grant said. “Either we’re going to lose him, or he's not going to get much better, and we just have to live with it.”

When Choichi asked how the son contracted the illness, Grant said he had no idea. Choichi then replied in Japanese, “That’s not an illness.”

“What the hell you mean?” Grant said. “You’re looking at a kid like this. Nothing is registering. He has to be fed by a tube. At the beginning when we talked to him, he could look at us, so we knew he was aware, but after the second month, there was no response. He was in a coma at that time. I didn’t voice it, but I thought to myself, ‘What the hell does he know about this kind of shit?’ You know.”

Coincidentally, Choichi was planning to perform in Hawaii and told Grant to sit tight and focus on the healing of his son. Choichi was more than just a teacher to Grant; he was like a father. Accordingly, Choichi promised, “The ancestors will not let him die.”

Soon after Choichi arrived in Honolulu with his wife and sister-in-law, they all piled into Grant’s white Lexus sedan and headed to the hospital to visit Grant’s son.

When they arrived, everyone entered the room except for Mrs. Terukina’s sister who waited outside. The sister was a kaminchu, or spiritual practitioner and asked Grant for permission, in Okinawan, to touch the son’s body. After he agreed, she touched his head and body.

When her hands came down to his lower back, she said that there was something in his stomach. Grant said it was a feeding tube. She said the boy would be fine, but that they should change the position of his bed.

The next day was a performance day. About 2:30 p.m, Grant received a call from a frantic relative at the hospital. She was in shock. It took her a while to get the words out to Grant: “He’s talking!”

The relative recounted that while she was watching over him, she had turned her back for a moment to do something when she heard, “Auntie, I’m thirsty, Can I have some water?”

Before this, Grant’s son had not spoken a word in two months and doctors also predicted that his speech would be the last of his abilities to return to normal. It was a miracle.

In the days following, Grant’s son’s health progressed. He was able to walk, talk and eagerly ate his father’s home cooking.

Mrs. Terukina and her sister told Grant that, now, it was time for him to seek out his roots and find his birth mother. This was a transformative time in Grant’s life and a new desire to answer the question “Who am I?” was born.

Who Am I?

I COME FROM MORE THAN ONE MOTHER,

MORE THAN ONE CULTURE,

MORE THAN ONE ANCESTRAL LAND I CALL MY HOME.

WHAT’S IN YOUR BLOOD MATTERS LESS THAN WHAT’S IN YOUR HEART.

To be continued >>

*This article was originally published in the Zentoku Foundation website.

© 2024 Jodie Chiemi Ching