I have embarked on a series of columns on the prolific and talented Tashiro family. I have already posted columns on Aijiro “Frank” Tashiro and three of his children, Kenji (AKA Ken), Aiko, and Aiji. Here I propose to add a study of Nao Tashiro, the wife of Aijiro and mother of their children.

Nao Tashiro was born Onaozan “Nao” Hasegawa in Echigo Province (as it was then called) in northeastern Honshu, Japan. Her father was an educated Japanese of Samurai ancestry, who retired after the Meiji restoration and ran a grocery business. When Nao was 12 years old, her parents moved to Hokkaido, hoping to better their lives, and left her behind in Honshu. Nao later told the story of going down to the beach to see her mother embark. The sea was rough and the people had to go in small boats out to the larger ones anchored off shore.

Nao’s mother turned to her and asked if she was quite sure she wanted to go to school in Sendai, or if she preferred to go on the boat with her parents to their new home. Nao replied, “It makes no difference whether I die at Sendai or whether I die in Hokkaido, so I will go to Sendai and do my best in school.”

In the end, Nao moved to Sendai, where she attended Miyagi Girls’ School, a Christian mission college. There she excelled in her studies and learned to speak English fluently. Under the influence of the American missionaries who taught there, the young Nao became a Christian. Sometime after, a friend in Sendai put Nao in touch with Aijiro “Frank” Tashiro, a young Japanese who had moved to the United States some ten years previously, and who had embraced Christianity. The pair started a correspondence.

After a half dozen hears in Miyagi, Nao left for America, with the support of Christian missionaries. According to later accounts, she was selected to do missionary work among Japanese in America. Like other Japanese Christians of her era, such as Jenichiro Oyabe and Kanzo Uchimura, she apparently expected that America would be a model Christian land and was bitterly disappointed when she arrived to discover racism, prostitution, and other unchristian attitudes among white Americans.

Nao moved to Chicago and there she met and married Aijiro. The two traveled around for some years, selling Japanese goods. (As mentioned previously, a 1905 article in the Herald-Palladium newspaper announced the visit of Mr. and Mrs. Tashiro to Benton Harbor, Michigan and extolled their display of rare imported Japanese art goods).

The pair then moved to Waterbury, Connecticut. The birth of their first son Kenji in 1906 was subsequently greeted by newspaper articles celebrating the birth of the first “pure-blooded Japanese” in New England.

Within a few years, the family moved to New Haven. Nao recalled that living there was not difficult for her because she was a Christian and spoke English well.

“We had no trouble finding nice houses to live in and the people were very nice to us, especially after they saw the president of the Winchester Rifle Manufacturing Company come to our home…to get me to translate letters for him as he had some business dealings with Japanese concerns. I think the fact that I spoke English made a difference in the community too. Anyway, we had many American friends. I had a private tutor in English for two years. I studied with Mrs. Tenny who was a graduate student at Yale University. I used to read the same books she studied and enjoyed it very much.”

During this period, the Tashiros ran shops and restaurants in New Haven and a Japanese art store in Rhode Island. Meanwhile, they had three more children in quick succession. Wherever they lived, they attended church and insisted their children go to church with them. Their business did well enough that they were able to buy a small cottage at the beach in Rhode Island.

There Aijiro and Nao made extra summer income by operating small beach-side amusements in tents–ring-toss and a kind of Japanese ping pong–for tourists. Nao later recalled, “We went to Rhode Island in the summer because Mr. Tashiro's art store could only succeed where there were many well-to-do people.”

The Tashiro family remained in New England for almost 15 years. In 1918, even as the U.S. was fighting World War I, Aijiro’s business failed. He went bankrupt and lost his business and the beach house. Since both Aijiro and Nao were committed Christians, they decided to migrate to Seattle and see if they could find missionary work to do in the Japanese community there.

Shortly after the family arrived, Nao gave birth to the family’s youngest child, Aisaku (AKA Arthur). The family settled in Bremerton, Washington, near the Navy Yard, where Aijiro worked as a cook in a restaurant in a neighbouring hotel owned by a Japanese immigrant named Yamashita. Aijiro then briefly opened his own restaurant.

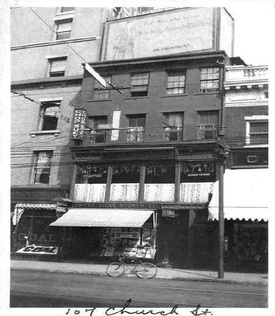

At length, Nao found a position in Seattle as an instructor at the Fujin Home, a shelter and school for Issei women who had lost their husbands that was run by the First Japanese Baptist Church. The Tashiro family took up residence in the home as well so that Nao could do her job, even as Aijiro worked as a cook and handyman.

To help the family finances further, Nao began tutoring Japanese in English. Once of her pupils was Miyoko Saito, the wife of Seattle consul-general (and future Japanese ambassador to the United States) Hiroshi Saito.

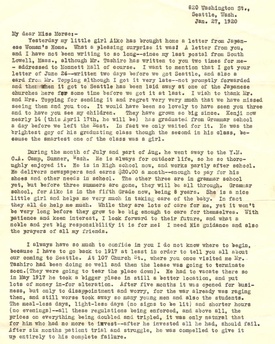

In 1924, Nao returned to Japan for a visit with her mother, bringing little Arthur with her, and stayed for five months. Upon her return, she agreed to be interviewed for an oral history by the professor and sociologist William Carlson Smith as part of his research for the notable 1925 Survey of Race Relations, a Canadian and American study of “Orientals” on the West Coast. She spoke candidly to Smith about her powers of acculturation.

“Unless people tell me that I am Japanese I forget it for I seem to belong here and to be a part of everything. My children feel more or less like that too. When we first came to Seattle and started up the street from the depot, we met some Japanese and my children said, ‘Oh mama, look at the Italians!’ They had seen so few Japanese in their lives that they did not recognize them.”

Nao believed strongly in education, which had served as her own gateway to a career in the United States. She planned to have her eldest son Ken study at the Y.M.C.A college in Springfield, Massachusetts and train for missionary work. To further his preparation for his collegiate studies, she enrolled him in high school in Attleboro, Vermont. However, he grew ill after a year, and was forced to return home.

When son Aiji finished high school, she was not able at first to arrange further study for him and he found a job working on the railroad. However, after several months, Nao arranged for him to enroll at the University of Cincinnati, with financial aid from Shiro Tashiro, who was a professor there. Her next son Sabro followed suit the next year. For daughter Aiko, Nao arranged a church scholarship so that she could attend Keuka college in upstate New York.

In 1928 the Tashiro family moved to Los Angeles, California, to join their oldest son Ken, who had already settled there. In August 1929, Nao contracted spinal meningitis and was sent to the County Hospital. Although she briefly rallied, she soon grew worse, and she died on September 16, 1929. Because she had suffered from a contagious disease, her body was cremated and the ashes were sent away, first for the funeral at the local Japanese Baptist Church, then back to Japan. Her death was recorded in Rafu Shimpo and the Japanese American Courier, the latter of which mentioned her long connection to the Seattle Baptist Church.

Nao Tashiro was one of the first wave of Japanese women who came to the United States as “picture brides,” to meet her betrothed for the first time. She thereby anticipated a generation of Issei women who had no other means of coming to the United States and often no other chance to marry.

She also was a prototypical Issei woman in being educated and fond of reading, in having several children, and encouraging those children to seek higher education—Nao’s ability to secure funding for her offspring was remarkable. Where she was most exceptional was in her ability to take on the majority language and religion of her adopted country, such that she could consider herself as fully American, and even run businesses that catered to mainstream Americans.

© 2024 Greg Robinson